![]()

Chapter 1: Beyond Biography

O’Neill and the Making of the Psychological Family

In reference to A Touch of the Poet (1939)—O’Neill’s play about an antebellum Irish immigrant family—Louis Sheaffer affirms, “Historic forces are at work here.” We can in fact say the same about all of O’Neill’s plays, notebooks, and letters. Biographers of O’Neill and critics of his plays have generally written within conventional notions of the scope of history (e.g., theatre history, literary history, intellectual history). But history also encompasses family life, privacy, gender, sexuality, subjectivities, and psychological discourse.1 While biographical contributions such as Sheaffer’s provide valuable insights into the family that shaped O’Neill, the history of American family life offers perspectives on the processes that shaped O’Neill’s family and the discourses of “the family” that influenced O’Neill in his playwriting.2 My aim here is to reassess several of O’Neill’s plays as well as biographical approaches to the playwright by situating them in the context of a history of nineteenth- and twentieth-century family life.

When I told friends I was writing a book on Eugene O’Neill, they frequently responded: you’re writing a biography? Their assumption isn’t surprising. A review of publications on O’Neill—popular and scholarly—will quickly give one the idea that O’Neill’s function within American literary and cultural history is to be stripped bare as the subject of biographies. Warren Beatty’s film Reds (1984), featuring Jack Nicholson as the O’Neill-who-was-obsessed-with-Louise Bryant, both reinforces and builds on this popular impression. O’Neill himself, of course, helped set the pattern for this biographical approach in interviews he gave over the years and, most notably, by thinly veiling episodes in his own family’s history in his final plays, Long Day’s Journey Into Night (1941) and A Moon for the Misbegotten (1943).

O’Neill’s biographers like to stress that he “was one of the most autobiographical playwrights who ever lived.”3 By implication, the literary and cultural value of O’Neill’s works is enhanced because they disclose their author’s psychological depth.4 Biographies of O’Neill take on the character of psychological studies of the dramatist, with closing chapters almost too painful to read.

Biographers tout O’Neill’s turbulent family history as a credential for his literary vocation as explorer of the self. Moss Hart’s blurb on the Gelbs’ biography praises their tome as having done justice to O’Neill’s agony—a tell-all psychotherapy for those O’Neills still afflicting themselves in that Great Theatre in the Sky: “[The] tormented spirits of all the O’Neills must be sighing with relief and thanks to Arthur and Barbara Gelb for a memorable work.” Notwithstanding O’Neill’s occasional practice of slugging his wives and snubbing his children (Shane and Oona O’Neill were written out of his will), Arthur Miller’s blurb frames O’Neill’s “failings” and his “agony” as essential to his subjective potency and theatrical magnitude: “[The Gelbs] have brought out his failings as a writer and a person only to leave him larger than before.” Theatre, Miller laments, is now “in the hands of triflers who will forever need the towering rebuke of his life and his work and his agony.” Prospective book-buyers are meant to buy the idea that the playwright’s gift to American drama was his own self-lacerating depth.5 Biographical depth and drama merge—the writing of drama read subjectively as personal crucifixion.6

Long Day’s Journey Into Night self-consciously capitalizes on the fact that its author is a member of a tortured Irish Catholic family whose men habitually hit the bottle. Irishness and drunkenness are two theatrical discourses of wounded subjectivity, stereotypes that lend added “literary” authority to O’Neill’s artistic credentials as diver in the depths.7 One perceptive reviewer of A Moon for the Misbegotten in 1947 drew attention to O’Neill’s use of the melodramatic Irishman of myth and literature: “[His] characters . . . are actually dark, eerie, Celtic symbol-folk . . . who beat their breasts at the agony of living, battle titanically and drink like Nordic gods, but are finally seen to wear the garb of sainthood and die for love.”8 Images of the modern “dysfunctional” psychological family, tormented confessional Irishness, and stagy self-absorbed drunkenness, allied to one another, help establish the mid- and late-twentieth-century interpretive context within which O’Neill’s life—like O’Neill’s drama—is read as an expression of O’Neill’s quintessentially individual depth.

Within this biographical enterprise, history serves as backdrop for the personal life that truly accounts for the playwright’s aesthetic motivations.9 Travis Bogard contends that O’Neill’s “writing was really dedicated to exploring a private world, the life of a few people [principally the four O’Neills] shut in a dark room out of time.” Although Bogard notes that Mourning Becomes Electra (1931) (based on the Oresteia) should be read in the context of “the twentieth-century Greek revival,” his central premise is that the trilogy “emerged as the end product of private necessity.”10

Biographical approaches to O’Neill often assume the guise not only of pop psychological case studies, but of guessing games whose object is to identify the four O’Neills who have been recast in various disguises as O’Neill’s characters. O’Neill’s family is represented as the allegorical key that opens the door to his conflicted psyche, his worldview, and his plays.11 “The child is essential to the understanding of the man,” asserts Sheaffer: Eugene “never really left his mother and father.” Although O’Neill was a playwright, “not a do-it-yourself psychoanalyst,” writes Bogard, his dramas fixated on “four people he obsessively sought to understand.”12 O’Neill’s biographers religiously reproduce this “obsession,” as the subtitles of Sheaffer’s biography show: Son and Playwright (vol. 1) and Son and Artist (vol. 2).

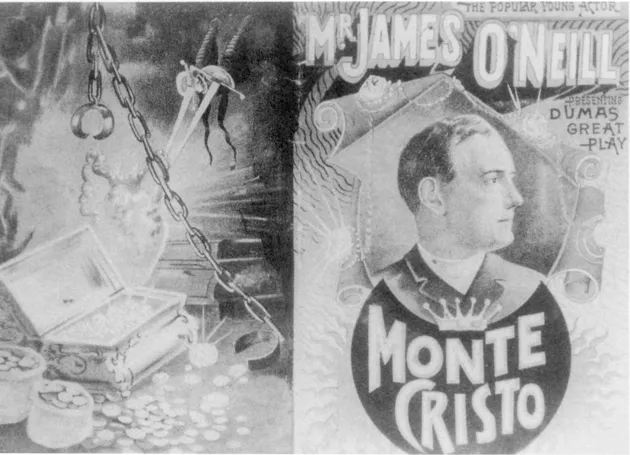

Figure 9. Promotional flyer of James O’Neill in The Count of Monte Cristo. Sheaffer-O’Neill Collection, Connecticut College Library.

To be sure, Eugene O’Neill’s family—like the Tyrones in Long Day’s Journey—was torn with conflicts. James O’Neill (1846–1920), born in Kilkenny, Ireland, lived there for only a few years before the potato famine drove his family, like multitudes of other impoverished Irish families, to America. The O’Neills emigrated to Buffalo, New York, and soon after tried to establish themselves in the slums of Cincinnati, Ohio.13 In Long Day’s Journey James Tyrone reminisces over a childhood rocked by poverty, evictions, machine shop labor, and abandonment by his father, who retreated to Ireland and died.

But by 1866 James O’Neill found his niche in the theatre and steadily built his reputation as a promising Shakespearean actor. In 1883 he turned Charles Fechter’s melodrama, Monte Cristo, into a moneymaker, playing Edmund Dantès escaping from Château d’If three thousand times (until his mid-sixties) (Figure 9). Three decades of Monte Cristo reruns made his fame and fortune (and, as Tyrone recognized, arrested the development of his talent). James O’Neill died of intestinal cancer, leaving his wife Ella an estate—mostly realty in New London, Connecticut—worth $150,000, no small sum in the early twenties.14

Figure 10. Photograph thought to be of Mary Ellen (“Ella”) Quinlan O’Neill, “lace-curtain Irish.” Yale Collection of American Literature Photographs, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

Mary Ellen (“Ella”) Quinlan O’Neill (1857–1922) was born in New Haven, Connecticut. Her parents, like the O’Neills, also fled the devastating conditions in Ireland. They moved to Cleveland, where Ella’s father, Thomas, thrived as the owner of a retail shop and later a liquor store. Unlike the O’Neills, they quickly climbed into the ranks of the middle class (something Ella never let her husband forget) (Figure 10). Ella spent her high school years at the exclusive St. Mary’s Academy, the convent that profoundly shaped her Catholic self-image. After graduating from St. Mary’s she saw James O’Neill perform, met him, and—swept off her feet—pursued and married him. A summary that Eugene wrote of his life in 1926 sketches what happened next:

M—Lonely life—spoiled before marriage (husband friend of father’s—father his great admirer—drinking companions)—fashionable convent girl—religious & naive—talent for music—physical beauty—ostracism after marriage due to husband’s profession—lonely life after marriage—no contact with husband’s friends—husband man’s man—heavy drinker—out with men until small hours every night—slept late—little time with her—stingy about money due to his childhood experience with grinding poverty.15

A year after her wedding, Ella gave birth to Jamie. Five years later Edmund was born and as an infant contracted measles from Jamie and died. Ella was stricken with guilt because she was on tour with her husband and had left her two boys behind. In 1888, Eugene’s birth was excruciating for Ella. Her doctor prescribed morphine (Mary Tyrone called him a “quack”) and turned her life-after-birth into a nightmare of addiction. There were other problems too, writes O’Neill: “She pleads for home in [New York] but [James] refuses. This was always one of her bitterest resentments against him all her life, that she never had a home.”16 They resided in hotels (even during long stays in New York City) and kept a summer house on the Thames River in New London—the setting of Long Day’s Journey. Ella battled her addiction with only intermittent success—she also drank—until she returned to a convent in 1914 or 1915 and was cured.17 After James’s death in 1920, Ella grew “more self-assured”18 and administered her husband’s estate with great skill. She died of a stroke in 1922.

James O’Neill Jr. (1878–1923) was a gifted youth who seems to have plunged headlong into a downward spiral when—as Jamie Tyrone put it in Long Day’s Journey—he first “caught [his mother] in the act with a hypo.” His guilt over infecting Edmund with measles and his despair over his mother’s addiction (Jamie Tyrone: “I’d never dreamed before that any women but whores took dope”) drove him to spend his adolescence drinking and “whoring.” He was expelled from Fordham for dissolute behavior in his senior year and worked off and on as an actor thereafter, though never seriously (Figure 11). After the “old man’s” death, Ella’s poise inspired him to sober up. But about the time of her stroke he had resumed his descent and drank himself to death a year and a half after her passing.

From early childhood Eugene (1888–1953) was close to Ella. His 1926 summary recalls: “Absolute loneliness of M at this time except for nurse & few loyal friends scattered over country—(most of whom husband resented as social superiors)—logically points to what must have been her fierce concentration of affection on the child.”19 O’Neill picks up the thread in a letter to the critic, Arthur Hobson Quinn: “After that, boarding school for six years in Catholic schools—then four years of prep. at Betts Academy, Stamford, Conn.—then Princeton University for one year (Class of 1910)—was an attempt at a ‘sport’ there with resulting dismissal.”20 The last straw at Princeton was when Eugene, on a drunken binge, smashed some railroad property. His adolescence, in part modeled on Jamie’s, was spent boozing and “whoring.” Both sons refused to fulfill their mother’s middle-class aspirations for them. Eugene read widely—as Edmund’s bookcase in Long Day’s Journey suggests (3:717)—but his interest in radical books challenged conventional middle-class assumptions.

Figure 11. James O’Neill Jr., on right, in a promotional photograph of the play The Traveling Salesman. Harvard Theatre Collection, Harvard University.

Between 1907 and 1916 he worked as a secretary of a mail order house, went prospecting for gold in Honduras, toured a bit with his father’s company, gained experience as a seaman (always proud of his promotion from ordinary seaman to able seaman), married Kathleen Jenkins (1909), fled from his wife (1909), became a father in his absence (Eugene Jr. was born in 1910), divorced (1912), studied Nietzsche, Strindberg, Shaw, and Ibsen as well as anarchist and socialist theory, did a stint as a reporter in New London, and entered a sanitarium for TB, where he convalesced for six months. “After I was released,” he continues, “started to write [plays] for first time. . . . In that winter, 1913–14, wrote eight one-act plays, two long plays. . . . In 1914–15 went to [Professor George Pierce] Baker’s 47, Harvard. Winter 1915–16 in Greenwich Village. Summer 1916 came to Provincetown, joined Provincetown Players.”21 The rest is literary history.

Thus Eugene grew up witnessing a constant dramatization of repression, guilt, denial, confession, compulsion, and ambivalence—as well as the intersection of class and gender tensions. While it is tempting to isolate this emotionally supercharged familial unit as the determining force in O’Neill’s life and work, it must be stressed that the four “haunted” O’Neills—as intense and as “personal” as they were—enacted their dramas within history and ideology. The biographical reflex to concentrate explanation on O’Neill’s private family and to detach the personal from certain dimensions of the historical process is at once reductive and revealing. Such biographical approaches reproduce, as O’Neill did himself at times, a twentieth-century psychological common sense—an ideology of the personal—that views the family-as-psychological fate.22 We would do well to keep in mind sociologist Richard Sennett’s reminder that “the alien world organizes life within the house as much as without it.”23 Literary biographers too rarely think of biography as a genre not only of literary, intellectual, and cultural history but also of the history of family life.24

Psychological ...