![]() PART I: LOCALISM IN TRANSITION

PART I: LOCALISM IN TRANSITION![]()

1 THE CONTOURS OF SOCIAL POLICY

Post-Reconstruction southerners shared a common tradition of governance. Imbued with rural republican traditions, they despised concentrated power, most of all the governmental coercion and intervention that they believed anticipated military dictatorship and a negation of personal liberty. Like their parents and grandparents, they tolerated the functioning of local, state, and federal governments only under strict constraints. This tradition of governance placed near-absolute control in the hands of local instrumentalities, which, in turn, functioned more or less independently of any outside control. The operation of local government was rarely democratic; power, especially in rural communities, was lodged in few hands. Yet what most often mattered to the people involved was that, in this hierarchical system, the local community enjoyed primacy in the management of public affairs.

CATEGORIES OF SOCIAL POLICY

In the nineteenth century the cultural setting for social policy—broadly defined as any exercise of governance designed to shape individual and community behavior—was distinctive. Aside from postmasters and an occasional tax collector, the federal government rarely touched the lives of southerners in the isolated rural communities and villages that the great majority of them inhabited. The role of state and local governments was no greater. In such areas as public education, public health, the regulation of moral behavior, and public welfare, state and local officials scrupulously respected home rule and the sanctity of local autonomy. Public welfare—community responsibility for the care of the poor, infirm, mentally ill, and dependents—offers one example of nineteenth-century social policy in operation. By sponsoring poorhouses and apprenticing the poor, county and parish governments extended relief by establishing a sort of social safety net that provided for the destitute and prevented outright starvation. Yet this welfare policy was rooted in a traditional view of charity that sought to discourage dependency, assumed that poverty was the product of individual character flaws rather than social environment, and stigmatized relief recipients.1

Public education was another important example of social policy in operation. While New England and the Midwest established publicly financed, tuition-free common schools between 1820 and 1860, the South created a more elitist structure. Antebellum southern schools, of course, excluded blacks, both free and slave; but even whites had only limited access to common schools. Underfunded by states and localities, they operated in erratic fashion, barely surviving the shabby poverty and popular hostility that hobbled them. Their designation as charity schools or free schools —a term that survived for much of the nineteenth century—set them apart from northern common schools. The fate of southern free schools also exposed cultural attitudes that were strongly hostile toward public education, beneath which lay a fundamentally different conception of education and social policy. Rather than being the symbols of a common culture of literacy, antebellum southern schools were seen as a poor man's alternative to private and denominational education. Like the poorhouse, free schools—in a culture that stressed independence and feared white “slavery”—became stigmatized as charity institutions.

During and after Reconstruction, the common school model slowly superseded the free school model. Mississippian Belle Kearney remembered that during the immediate postwar years, it was considered “scarcely respectable” to patronize public schools; those who taught in them were “brave indeed.” In what she called a “revolution” that reflected a “blossoming” of public opinion, schools became permanent fixtures of the southern social landscape. Political and constitutional factors spurred on attitudinal changes. By the 1880s, as a result of Reconstruction state constitutions, every southern state required universal education, including black education. The connections between Reconstruction and education were close, for northern and southern Republicans believed that grafting New England–style common schools on the South would subvert the aristocratic social order. Other features of the New England model of common schooling figured prominently in late nineteenth-century schools. Tuition-free and financed by state and local property taxes, the new southern common schools were administered by a skeletal state bureaucracy headed by a state superintendent who was located in the state capitol; they were operated at the local level by county superintendents and local trustees. Yet, rather than the transplantation of northern cultural institutions to the South, what occurred was a process of assimilation of northern educational values and institutions into southern culture. Although the New England township system supplied the popular model for Reconstruction school administration, there was significant variation. Some states had county-run systems, others had schools operated by townships, and still others granted total autonomy to neighborhoods. In some states, school officials were elected; in others, they were appointed.2

Although important differences persisted among whites and blacks, both races embraced education during the post-Reconstruction era. The approval by blacks was immediate, enthusiastic, and millennial; in their communities, schools symbolically but decisively repudiated the intellectual and psychological underpinnings of slavery. Many whites clung to antebellum attitudes; their acceptance of Reconstruction-style schools came slowly. Although the social stigma of charity schools persisted into the 1880s, disappearing only gradually, southern whites steadily incorporated public schools into the fabric of community life. As southerners adapted to schools, schools adapted to southerners. Facing an often-hostile public opinion, school officials discovered that survival required a recognition of the limits of social policy. Although school superintendents emerged as figures of some stature, few of them had any illusions about their powers. Their main purpose was to secure community approval and support for education. Real control lay with communities, on whose good favor and participation the effective functioning of schools depended, and power over educational policy resided in the dispersed neighborhoods of the rural South.

Public health similarly functioned under a community-controlled administrative system. Although a few states possessed an antebellum public health apparatus, like the educational system, it underwent redefinition during Reconstruction. Even so, only as a temporary response to the emergency of epidemics did states begin to establish public health systems. The creation of the National Board of Health in 1878—in response to a devastating epidemic in the Mississippi Valley in that year—marked a brief and largely unsuccessful experiment in a coordinated national public health policy. New state and local health boards came into existence during the 1870s and 1880s. In states such as Alabama, Louisiana, and Florida, which contained ports of entry for tropical diseases, state health bureaucracies were granted strong emergency powers.3 In Alabama, the legislature in 1875 revitalized the antebellum State Board of Health by making the state medical association the state board of health and investing it with new powers. It also empowered the state board to convert county medical associations into county boards of health, whose primary duties were to collect and record vital statistics. In Florida, a state health system was created after the devastating impact of a yellow fever epidemic in 1888. In response, the assembly enacted legislation creating both a State Board of Health and a system of maritime quarantine.4

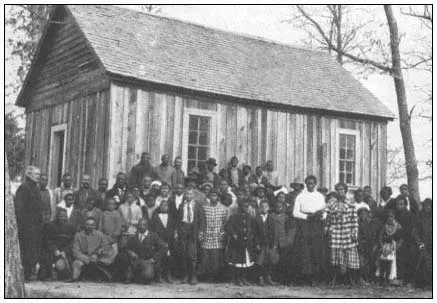

Keithville School, Caddo Parish, Louisiana, ca. 1920

(Courtesy of the Special Collections Department, Fisk University Library)

The regulation of the manufacture, distribution, and consumption of alcohol is another example of the limited scope of prebureaucratic governance.Rather than regulating or directly attempting to limit alcohol consumption, the state awarded franchises or officially sanctioned permits. As with schools and public health, public power was abdicated to private, nongovernmental groups. At the local level, this meant that the execution of policy fell mostly to local power blocs. Beginning in the colonial period, most southern states, in part to control consumption and in part to obtain revenue, adopted a system that provided for fees and licensing and the nominal regulation of taverns and saloons. During the Civil War the federal government also imposed an excise tax on whiskey manufacturers, which the U.S. Internal Revenue Service enforced.5

Yet the implementation of alcohol policy also operated under limitations that public opinion and local custom imposed. A tradition of drinking balanced restrictions on alcohol. Visitors often noted alcohol-induced southern hospitality; if anything, the prevalence of drink had increased by the end of the nineteenth century. Because of these strong traditions of alcohol consumption, nineteenth-century state and local governments made few efforts at regulation. Although local option spread across the rural South in the post-Reconstruction period, there is ample evidence that it was violated almost routinely. Despite local option laws, federal internal revenue agents regularly collected taxes in dry counties. Blind tigers (illegal saloons) were a common phenomenon in the post-Reconstruction South; in the absence of legislation to prevent the importation of alcohol from wet into dry counties, bootleggers worked out cunning and effective systems of distribution.6

Whether in education, health, or public poor relief, southern state and local governments exercised social policy in a manner that most late twentieth-century Americans would consider strange, even alien. Rather than providing continuous, regular, and bureaucratic government, states and localities were concerned primarily with factors such as political party, class, locality, kinship, and denomination. Few features of social policy were compulsory or coercive; except for grave emergencies, the sanctity of the individual and of personal liberty remained sacrosanct. This was a system of government in which bureaucracy played no role at all.7

PUBLIC OPINION AND SOCIAL POLICY

Social policy and governance in the post-Reconstruction South were shaped by and responsive to public opinion. For nineteenth-century southerners, as for most Americans, public opinion most commonly mirrored political culture, which combined an ideology of republicanism and resistance to power with a structure strongly shaped by partisanship.8 Southerners shared this political culture, and its accompanying political attitudes, with other Americans. Yet other distinctive conditions also made social policy and its relationship with public opinion unique in the rural South. The lack of good overland transportation facilities made the already-imposing barriers of a large number of often-impassable streams and mountains formidable. The impact of the South's rural landscape was striking to northern visitors, many of whom noticed that crossing the Potomac from Washington, D.C., into Virginia brought stark changes. When a northern-born traveler, Olive Dame Campbell, visited the South in 1908, she was struck by its exotic qualities. She noted changes in the landscape once her train crossed into Virginia. The rural qualities of the South immediately struck her; she noted the absence of large cities and the monotony of “stretches and stretches of woodlands and corn fields.”9

Even starker changes awaited the more adventurous travelers willing to depart the railroads. Harvard historian Albert Bushnell Hart visited the South and in 1910 published his observations in a sociological guidebook for northern visitors, The Southern South. Hart urged students of southern life to probe beneath the surface. He wrote that visitors who went only to boom towns, textile centers, mining and lumbering centers, and forges and foundries accepted stereotypes about widespread progress. Yet the prevalence of change did not always mean progress, for once observers entered the hinterlands, as did Hart, they discovered a very different environment, one composed of “straggling” cities, “small and often decaying towns,” and “remote and isolated” rural communities.10

This social environment was distinctive. The fact that an undiluted “Anglo-Saxon” race populated the South fascinated Hart, as it did many other early twentieth-century observers. But while he praised white southerners for their racial purity, their backwardness baffled him: southern Anglo-Saxons, he wrote, were as “lazy, unprogressive and densely ignorant” as the blacks with whom they lived in close proximity, while they were also, he believed, indisputably “brutal, licentious, monicidal, and cruel.” But the white masses were dominated to an extraordinary extent by class constraints. Although he acknowledged that “a comparatively small number of persons” made the “great decisions” in all societies, Hart asserted that southerners lived under a rigid hierarchy of elite domination; in no other region did a small aristocracy exercise such prestige and influence. For Hart, elite control meant leadership by the “best” people. With some admiration, he mused that—to the amazement of northerners—in the South the well-to-do, the cultured, the educated, and the well connected absolutely controlled society, while public opinion showed unusual unity. In most categories of public behavior and social policy, there existed a “recognized standard.” Any deviations from that standard were regarded with great suspicion.11

Yet public opinion also cut across class lines. Despite the rigid social hierarchy that Hart suggested, community solidarity against outside threats was a significant factor. Southerners rallied against northern intervention; North Carolinians and Mississippians expressed equally enthusiastic state patriotism, and the basic loyalty was to the community, most often to the rural neighborhood. Encircled by their kin and churches, southerners recognized a fundamental individual and group identity, and, at this community level, they forged their strongest allegiances. The settlement pattern of the colonial period had much to do with determining these attitudes: rather than settling in compact villages typical of Europe and New England, most southerners followed a pattern of dispersed settlement. The result was a rural isolation that became, over the centuries, a culturally determinative characteristic. Most people, Hart observed, lived in sparsely settled and dispersed communities that had retained frontier characteristics. Villages with pretentious-sounding names were nothing more than hamlets of several houses, where churches, schools, and “mournful little cemeteries” often lay at a crossroads. White Carolinians, wrote rural sociologist Eugene Cunningham Branson, lived in isolated farms; compactly settled rural communities, “conscious of common necessities and organized to secure common advantages,” were rare. A concept of community meant one thing in the Middle West and the...