![]()

1 The Roots of Ocracoke English

The Ocracoke dialect, or brogue, is one of the first things visitors to the island notice. This dialect is most distinctive for the way its speakers pronounce the i vowel as more of an oy, so that high and tide sound like hoi and toide. But a number of other traits also contribute to the “hoi toider” sound that is quite unlike the speech of the mainland southerners who are Ocracoke’s neighbors. For example, Ocracokers give the ow sound in a word like town an unusual pronunciation that makes the word sound something like tain. They also pronounce their r’s more than do most mainlanders. Speakers from many parts of the eastern North Carolina mainland, especially older speakers, tend to pronounce words like farm and cart as fahm and caht, without the r sounds; Ocracokers, however, will most likely leave the r’s in. Ocracoke English is marked by some unusual grammatical variations, and visitors to the island might hear sentences such as “People goes to the store” instead of “People go to the store” or “It weren’t me” instead of “It wasn’t me.” And what distinctive dialect would be complete without its share of unique words? Ocracokers are well known for their distinctive vocabulary, especially the word mommuck, which means ‘to harass or bother’, as in “Don’t mommuck me; I’ve had a hard day.” Other dialect words include quamished, which refers to having an upset stomach (as in “That ferry ride made me feel quamished”), and call the mail over for ‘mail delivery to the island post office’. (“Is the mail called over yet? I’m expecting an important letter.”)

People attempting to describe Ocracoke speech to outsiders often call it Shakespearean English, Elizabethan English, or Old English. The Ocracoke brogue also seems to remind some people of Irish or Scottish English, since speakers of those language varieties are said to speak a “brogue” as well. In fact, the word brogue comes from the Irish term barroq, which means ‘to grab hold, especially with the tongue’.

On first consideration, Shakespearean English may seem like a good label for the Ocracoke brogue. After all, there were a number of explorations along the Virginia coast and North Carolina’s Outer Banks in Shakespeare’s day. And the first permanent English settlement in the New World was established in Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607, a full nine years before Shakespeare’s death. So it is probable that the first settlers on the Outer Banks spoke a variety of English similar to that of Shakespeare, Sir Francis Bacon, Queen Elizabeth, and their contemporaries.

It is tempting to think that this older form of English might have been preserved on Ocracoke. After all, the island is separated from the mainland by twenty miles of water, well removed from the language evolution that occurred there over the centuries from Elizabethan times to the present day. A quick comparison of today’s brogue with Shakespeare’s writings reveals some interesting similarities that suggest Outer Banks English is indeed related to the English of almost four hundred years ago. For example, the word mommuck was widely used in sixteenth-century England, though its meaning was different back then (it actually meant ‘to shred’). Mommuck even appears in one of Shakespeare’s plays: “Hee did so set his teeth, and teare it. Oh, I warrant how he mammockt it” (Coriolanus I, iii, 71).

Is it possible, then, that Ocracoke English is really Elizabethan English, as some people claim? What a find that would be for scholars who study the histories of languages! Unfortunately, things aren’t that simple. One fact about languages that all linguists agree on—and that many nonspecialists are well aware of—is that all languages, and all dialects, are constantly changing. If it weren’t for the changing nature of language, varieties like Elizabethan English wouldn’t have developed in the first place. The way Shakespeare talked or wrote would be the way we talk now. And anyone who has ever read one of his plays, or has even read something written in the 1800s, knows that such is not the case. In fact, the further back in time we go, the harder it becomes to understand texts written in what we think of as our own language. Thus, although it is possible to read and understand Shakespeare (at least with annotations), it’s almost impossible for the nonexpert to pick up a work by Chaucer (who died in 1400) and be able to understand it unless it has been translated into modern English. And if we go even further back than that, English begins to look like a completely different language.

Languages change so drastically over time that linguists routinely separate a developing language into different stages or periods in order to analyze those changes. English is usually studied in terms of four significant historical periods. The first, Modern English, is the language we speak today. The second, Early Modern English (ca. 1500–1800), covers the Elizabethan period as well as the period of early exploration in the New World, including the first settlement on Ocracoke in 1715. The third, Middle English, is the variety spoken by Chaucer (ca. 1100–1500). And the fourth, the oldest form of the language, is Old English, which was spoken in England up until shortly after the Norman Invasion led by William the Conqueror.

To illustrate the point that languages change—sometimes radically—over time, here are four versions of the first verse of the Lord’s Prayer, one from each period in the history of the English language:

The Old English version of more than a thousand years ago may not look much like English at all. But if you examine it closely, you can see the beginnings of a few Modern English words, such as fader for father, urer for our, and noma for name.

The tendency of languages to change over time has given rise to the different dialects of English that are familiar to us today. Speakers of a common language who become isolated from one another will gradually begin to speak different dialects of that language. Isolation can result from physical barriers such as mountains or water, or it can result from strong social or ethnic divisions. The essential quality of isolation, however, is that isolated people do not communicate or otherwise interact with other groups of people on a regular basis. Languages or dialects in secluded areas continue developing as time goes by, but development in different areas takes a unique course in each one, especially when contact between these areas is limited. Thus, Early Modern English split into American and British variants because the Atlantic Ocean lay between the colonists and their relatives at home. And the English that was originally brought to the New World already consisted of numerous dialects. The first settlers on Ocracoke most likely spoke a very different dialect from early colonists in Boston. Further, it is quite probable that even the small handful of people who settled the island came from a number of different areas themselves, each with its own dialect. All the disparate forms of speech brought to this country eventually evolved into the American English dialects we recognize today, such as southern, New England, and, of course, Outer Banks English.

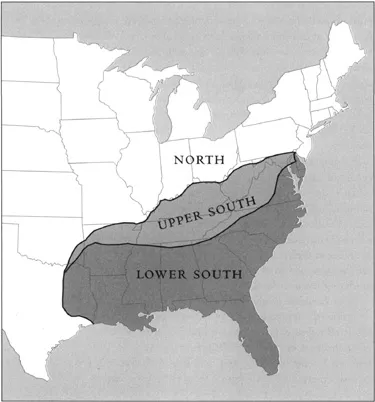

Defining and naming the dialect areas of the United States is a complex matter, and dialectologists throughout the twentieth century have continued to propose various ways of dividing up the country’s regional speeches. For our purposes in this book, we have adopted the relatively straightforward divisions for which most people already have an intuitive feel. When we refer to southern dialect areas, we mean those areas south of the Mason-Dixon line between Pennsylvania and Maryland. The South itself may be divided into several sub-regions, including Appalachian or highland southern and lowland southern (that is, the nonmountainous South). Within North Carolina, the lowland area encompasses the Coastal Plains region in the eastern portion of the state as well as the Piedmont region in the center of the state. Map 1 illustrates these dialect divisions.

It is important to remember that even when one group of speakers becomes totally isolated from other speakers, its language continues evolving, but in a different direction from everyone else’s. Ocracoke might have been cut off from the mainland during its early history, but its language never became stagnant. Even if Shakespeare himself had built the first house in Ocracoke Village and then had traveled through time to visit the Outer Banks today, he would have a hard time understanding the language of his descendants on the islands, because the language he had originally brought to Ocracoke would have changed so much over the intervening centuries.

So, if Ocracoke English isn’t an Elizabethan dialect that has been frozen in time since the seventeenth century, then what is it? On what dialects of Early Modern English is it based, and in what directions did it evolve from that point of origin? Is it kin to today’s British or Australian English, as some tourists claim? Is it more like other American English dialects? Or is it unique, having evolved in ways that distinguish it from every other English dialect?

THE ORIGINS OF OCRACOKE ENGLISH

Beginning with their first explorations of the Outer Banks, British sea captains recognized that Ocracoke Inlet was a strategic passageway through the hazardous chain of barrier islands to mainland ports. Large ships could not pass through without assistance, however, so it was necessary to station pilots at the inlet to help guide the vessels. As more and more Europeans began inhabiting coastal Virginia and mainland North Carolina, ship traffic through Ocracoke Inlet increased to such a great extent that in 1715 the North Carolina Assembly passed what the old record books termed “An Act for Settling and Maintaining Pilots at Roanoke and Ocacock Inlett.” Thus Pilot Town, later renamed Ocracoke Village, was born.

Map 1. Dialect Areas of the United States (Adapted from Craig M. Carver, American Regional Dialects: A Word Geography [Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1987], p. 247)

The first pilots who built temporary homes in the new village were most likely of English origin. By the time the community began to take on the character of a permanent settlement, around 1770 or so, most of the British from whom today’s prominent island families are descended were already living on Ocracoke or in neighboring Portsmouth, across the inlet from Ocracoke Village. Many of these families had not immigrated directly from Britain but rather had lived for a while in the Virginia Tidewater area and the Albemarle Sound region of North Carolina. The surnames of these first inhabitants are still common on Ocracoke, including Bragg, Gaskins, Howard, Jackson, Stiron (today spelled Styron), and Williams. One well-known family, the O’Neals, are of Irish origin, as probably are the Scarboroughs, thought to be descended from Captain Edmund Scarborough, an Irishman who settled on the Eastern Shore of Virginia in the 1630s. Other Ocracoke families, such as the Austins, Ballances, and Midgetts, had established themselves on neighboring Banks islands before the turn of the nineteenth century.

What sort of English was spoken by early Ocracokers? We know for certain that it was some variety of Early Modern English, which, as mentioned above, is the name we give to the form of English spoken from some one hundred years before Shakespeare’s day until about two hundred years after his death. Some characteristics of Early Modern English that distinguish it from today’s Modern English include the use of several pronouns no longer common in our time, including thou for the singular you; different verb forms such as sate for the past tense of sit (as in “Yesterday she sate there”); -eth endings on certain verbs (“He sitteth”); the absence of the word do in places where we would use it today (as in, “Sits he in the chair?” and “Sit not there!”); and, certainly, many spelling differences that didn’t affect how the language sounded but greatly affected how it looked on paper. Some remnants of Early Modern English that we do find in the Ocracoke brogue include the addition of a- (pronounced uh) before verbs ending in -ing, as in “He went a-fishin’,” as well as the use of distinctive words like mommuck and quamished.

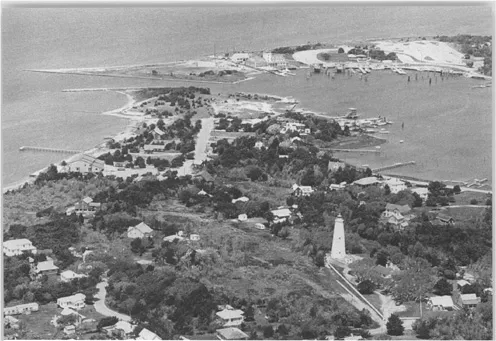

An aerial view of the lighthouse and Springer’s Point. (Photograph by Ann Sebrell Ehringhaus)

One notable difference between the early English brought to Ocracoke and today’s language was the pronunciation of certain vowels. For example, the ay sound in words such as name was pronounced like the vowel in Modern English cat, and the i sound in words such as high and tide sounded something like the vowel uh (as in but) followed quickly by ee (as in beet), resulting in t-uh-ee-d. This pronunciation is reminiscent of the i sound we hear on Ocracoke today, which many people think sounds like the oy in boy but which really falls somewhere in between the Early Modern English i sound and our oy.

Another Early Modern English vowel that sounds similar to the current pronunciation on Ocracoke is the ow vowel in a word like house, pronounced as uh (as in but) plus oo (as in boot), so that we get h-uh-oo-s. The ow sound on Ocracoke today is somewhat different from this earlier sound, since house comes out sounding something like hice rather than h-uh-oo-s. But both the ow and i sounds in current Ocracoke speech do come from their Early Modern English progenitors. Those same vowel sounds, which first came from England in the 1700s, developed along different lines in other American dialect areas. For example, in the mainland South tide is often pronounced as tahd, while in the North we find the long i of tide. On the other hand, in the Virginia Tidewater area, from which many of the Outer Banks’s first families came, we can hear a pronunciation for words like house in which the ow sounds very much like the Ocracoke version of this vowel.

Although Ocracoke English is based on Early Modern English, we need to remember that there were many dialects of that early language, just as there are of its equivalent today. There is some question as to exactly which forms of Early Modern English played a role in shaping the early Ocracoke brogue. Much of the American South was settled by people from the south and west of England. But early settlers along the coastal areas of the South, including some Outer Banks families, may have come from England’s eastern counties as well. We have found that today’s Ocracoke brogue displays many features from southern and western England, along with a number from eastern England.

It is also likely that early Ocracoke speech was influenced by the Irish and Scots-Irish varieties of English. Many of the first Europeans to settle in southeastern North America were of Irish rather than English descent. In fact, by 1790 the Irish constituted fully one-eighth of the white population of the South. The Scots-Irish, who came from the province of Ulster in what is now Northern Ireland, were even more numerous. At the time of the American Revolution, there were already 250,000 Scots-Irish living in America; and from then until the end of the nineteenth century, they made up the largest single white ethnic group in the South. Although most of the Scots-Irish settled originally in Pennsylvania rather than the American South, many of these early immigrants and their descendants eventually made their way southward to the Carolinas.

The variety of Early Modern English spoken by ...