eBook - ePub

The Company They Kept

Migrants and the Politics of Gender in Caribbean Costa Rica, 1870-1960

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Company They Kept

Migrants and the Politics of Gender in Caribbean Costa Rica, 1870-1960

About this book

In the late nineteenth century, migrants from Jamaica, Colombia, Barbados, and beyond poured into Caribbean Central America, building railroads, digging canals, selling meals, and farming homesteads. On the rain-forested shores of Costa Rica, U.S. entrepreneurs and others established vast banana plantations. Over the next half-century, short-lived export booms drew tens of thousands of migrants to the region. In Port Limón, birthplace of the United Fruit Company, a single building might house a Russian seamstress, a Martinican madam, a Cuban doctor, and a Chinese barkeep — together with stevedores, laundresses, and laborers from across the Caribbean.

Tracing the changing contours of gender, kinship, and community in Costa Rica’s plantation region, Lara Putnam explores new questions about the work of caring for children and men and how it fit into the export economy, the role of kinship as well as cash in structuring labor, the social networks that shaped migrants' lives, and the impact of ideas about race and sex on the exercise of power. Based on sources that range from handwritten autobiographies to judicial transcripts and addressing topics from intimacy between prostitutes to insults between neighbors, the book illuminates the connections between political economy, popular culture, and everyday life.

Tracing the changing contours of gender, kinship, and community in Costa Rica’s plantation region, Lara Putnam explores new questions about the work of caring for children and men and how it fit into the export economy, the role of kinship as well as cash in structuring labor, the social networks that shaped migrants' lives, and the impact of ideas about race and sex on the exercise of power. Based on sources that range from handwritten autobiographies to judicial transcripts and addressing topics from intimacy between prostitutes to insults between neighbors, the book illuminates the connections between political economy, popular culture, and everyday life.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Company They Kept by Lara Putnam in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Latin American & Caribbean History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One: The Evolution of Family Practice in Jamaica and Costa Rica

Distant markets and local initiative have long set goods and people in motion around the western edge of the Caribbean Sea. The migrations that accompanied the booms and busts of export agriculture in Limón in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were episodes in a well-established trend. In coming chapters I seek to compare gender roles and kinship practices in Limón between groups and over time. But what are the baseline cultural patterns against which to measure change? Which are the relevant group boundaries? The answers are not self-evident. The story of each people in the region is a Rashomon tale in which the boundaries of embattled identities are revealed to be themselves the results of previous conflicts and past convergences. Claims about racial essence, national character, and cultural divides came to dominate political rhetoric in the region in the twentieth century. Such arguments depended on a willful forgetting of the stories that went before. Diversity, capitalism, and change did not reach the Caribbean shore on an iron locomotive driven by Yankee impresario Minor C. Keith. By the middle of the nineteenth century no population in the region had been untouched by the world market and European expansion—though the terms of the engagement had varied sharply across localities and over time. No polity was ethnically homogeneous—though some nations were more committed to making that claim than others. Even within a single place, among a self-identified people, patterns of gender and kinship defied simple generalization. No model of domestic authority was unquestioned—though domestic hierarchies received stronger official backing in some places than in others. No gender roles were universal—though some individuals had more culturally sanctioned alternatives than others.

The pages that follow offer a tale of two colonies, the island of Jamaica and the province of Costa Rica. I seek to trace evolving patterns in relationships between men and women and families and states. Official interest in popular kinship was frequently non-existent, occasionally intense. In the final years of the eighteenth century imperial agents made unprecedented efforts to engineer family practice in the colonies, as the British Crown tried to stimulate slave populations’ natural increase and the Spanish Crown sought to halt racial mixing by putting the weight of law behind a particular definition of family honor. In both cases, such targeted projects had minimal impact. Instead, the most powerful effects of official policies on kinship practice were indirect. Within each society the evolving articulation of economic elites, state institutions, and labor regimes set the terms of popular access to land, credit, and markets. As the structural conditions men and women negotiated in their daily lives changed over the first half of the nineteenth century, so too did the families they created and the role they allotted the state within their family practice.

The Western Caribbean in the Atlantic System

More than 5,000 years ago footpaths and coastal waterways wound from the heart of modern Mexico to the highlands of modern Colombia. Below Lake Nicaragua, in the narrow southern extreme of Mesoamerica, three mountain chains run from northwest to southeast in what is today Costa Rica. By the years 1000 to 1500 C.E. climate, geography, and long-distance ties had shaped three distinct sociolinguistic regions in the area. The Central Region included the temperate highland basin and the valleys leading south to the Pacific coast; Gran Nicoya encompassed the tropical dry forests and savannas of the Pacific lowlands of modern Nicaragua and northwest Costa Rica; Gran Chiriquí spread over the isthmus of Panama and along the rain forests and mangrove swamps of the Caribbean coast well into what is now Nicaragua. Perhaps 400,000 people lived in these three regions combined.1 Until the 1500s the rise and fall of expansionist empires elsewhere had important cultural repercussions here, but limited political and demographic impact. With the arrival of military-commercial emissaries from the city-states of Castille and Aragon all this would change.

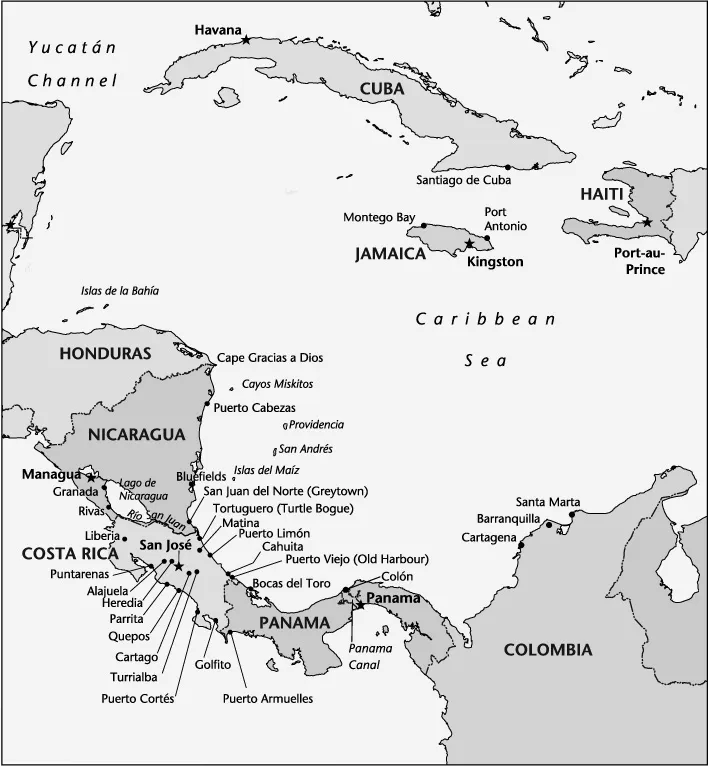

MAP 1.1. The Western Caribbean

The indigenous polities of Gran Nicoya were “pacified” and distributed as encomienda grants to individual Spaniards in the 1520s and 1530s, those of the Central Region four decades later. This was a land of sparse opportunity from the colonizers’ point of view. Descendants of Spanish adventurers who had not ended well eked out an existence in the eastern Central Valley, outside the city of Cartago where colonial officials and wealthy locals clustered. Forced resettlement had combined the tattered remnants of indigenous communities into a handful of pueblos in the Central Valley and central Pacific coast. “Free mulattos and pardos,” descended from African slaves who had managed to secure their own or their children’s freedom through purchase or manumission, made themselves indispensable in the colonial militias. Mulatto cowboys ran the Pacific plains cattle ranches of Cartago’s wealthy. On the alluvial flood plains of Matina on the Caribbean side, African slaves cultivated the cacao groves of absent masters, and perhaps a few trees of their own as well. Indigenous people from the southern mountains were periodically forced to labor on the Matina plantations of well-connected elites. Cacao was sold illegally to Jamaica-based traders for guns, clothing, and African slaves.2

As sugar plantations spread from Barbados to Jamaica, Nevis, and the Leeward Isles, more than 300,000 enslaved Africans were brought to Britain’s Caribbean possessions in the second half of the seventeenth century. Among West Africans arriving in Jamaica men outnumbered women by roughly three to two. European planters much preferred to purchase male laborers, while regions within West Africa varied widely in their eagerness to export female slaves. There, enslaved women were crucial to production and reproduction alike. Women performed the bulk of agricultural labor, and female slaves were integrated into their owners’ households as additional wives or as wives of their owners’ male slaves.3 Jamaican planters’ plans for their human chattel were less complex. The vast majority, men and women alike, were put to work in the cane. If to European observers black women’s fieldwork seemed proof of their de-sexed nature, on other points West African and European gender assumptions coincided. Technical or supervisory positions were naturally to be filled by men, domestic labor to be performed by women. In theory, under the plantation system slaves were economic inputs, not economic actors. But Jamaican markets came to depend on the economic initiative of the enslaved, who kept the island supplied with “hogs, poultry, fish, corn, fruits, and other commodities.”4 Kinship ties rather than formal institutions guided production, services, and commerce within the slaves’ economy.5

The customs that shaped sex and succor among West Indian slaves were those reconstituted by bondsmen and women themselves, within confines laid out by overwork, abuse, and early death. Developing kinship forms were shaped by the specific cultural assumptions brought by enslaved men and women; the greater or lesser heterogeneity of the slave population; the pace of arrival of “Salt-water Negroes”; the strictures of plantation size, work regime, and owner’s fortunes; and the distance and degree of contact with other plantations or towns. Given the multiple sources of diversity, the broad similarity of kinship patterns developed among Caribbean slaves is striking. Households with more than one co-residential conjugal couple were rare. Only men of particularly high status had multiple wives, usually in separate households. Women typically entered into co-residential unions after the birth of their first or second child. The small size or sex imbalance of some plantations encouraged a commuting family culture, in which travel between locales maintained contact between husbands and wives, parents and children.6

The Caribbean islands had become by the end of the eighteenth century “the most valued possessions in the overseas imperial world, ‘lying in the very belly of all commerce,’ as Carew Reynell so aptly described Jamaica.”7 The booming trade with the island plantations far outshone the entrepôt trade with the rimlands. Yet European demand for indigo, cacao, turtle-shell, turtle meat, and sarsaparilla continued to bring traders and collectors to the Caribbean lowlands of Central America. Much of this commerce was controlled by the Miskitu, an expansionist indigenous tribe that came to incorporate large numbers of Africans and their descendants: survivors of a legendary shipwreck, escapees from the Honduran mines, refugees from the growing slave economies of the Western Caribbean islands. Miskitu hunted green turtles (Chelonia mydas) at their feeding grounds southeast of Cape Gracias a Dios and at their nesting grounds at Turtle Bogue, midway between Matina and Bluefields. Local manipulation of imperial rivalries prevented either Spain or England from gaining control of Mosquitia, whose population had grown to 20,000 by 1759.8 Two and a half centuries after “conquest,” colonial rule in southern Mesoamerica remained limited to the central highlands and Pacific plains, with only a handful of guard posts and two small settlements in the vast Caribbean lowlands. This was in spite of the unprecedented numbers of troops and decrees dispatched into the region in the last decades of the eighteenth century as part of a broad effort by the Bourbon monarchs of Spain to make bureaucracy more responsive, tax collection more efficient, trading monopolies more profitable, and colonial borders more secure.

Race and Honor in Late Colonial Costa Rica

For tightened lines of transatlantic authority to be effective it would be necessary to shore up the internal frontiers of colonial society as well. The Spanish American bureaucracy was designed to rest upon a population neatly split among racial categories, which determined legal obligations and privileges and in theory corresponded to economic position. Geographic, occupational, and administrative divides were meant to maintain Indian tributaries, black slaves, and Spanish nobles as stable and distinct social groups. But by the eighteenth century the rapidly growing numbers of castas (people classed by themselves or others as of mixed ancestry) indicated the breakdown of such divides. Booming indigo production around San Salvador drew indigenous workers from their communities of origin. Growing urban economies provided entrepreneurial opportunities for the children and grandchildren of domestic slaves. Intermediate social identities like mestizo and mulatto swelled accordingly, comprising by 1776 the majority within every province of the Kingdom of Guatemala except Guatemala itself.9 The economic dynamism the Bourbons sought to advance was destroying the social order according to which they meant its fruits to be reaped. Thus the Bourbon state directed its attention to matters of sex and status in the colonies. The Royal Pragmatic of 1778 widened parental control over marriage choice in order to halt the spread of unequal unions that “gravely offend family honour and jeopardize the integrity of the State.”10 Subsequent edicts within the colonies defined precisely which socio-racial groups were subject to consent requirements, thereby delineating those whose couplings were beneath state notice and those who, despite known African ancestry, might have honor to lose.11

By 1801 the population of the province of Costa Rica had reached 52,591—which is to say, slightly less than the total number of African slaves imported by Jamaican planters over the previous five years.12 Contemporaries guessed that 2,500 more indios lived beyond the colony’s effective borders, in Talamanca, Bocas del Toro, and Guatuso (the densely forested valley south of the Río San Juan). Census-takers tallied 4,942 Spaniards, 8,281 Indians, 30 blacks, 8,925 mulattos and zambos, and 30,413 ladinos and mestizos.13 But other documents of the era suggest that in practice racial labels were rarely used to identify social collectives. Rather, the populace was divided into a tiny elite of Spaniards and European immigrants, known as gente noble or gente de bien, and a heterogeneous but culturally converging mass of gente del común—common folk.14 Over the course of four generations the numbers of people claiming mixed racial heritage, when asked, had mushroomed. Mestizos surged from 4 percent of the population in the 1720 census to 58 percent in 1801, a change in racial identification that must have been the result of both widespread extralegal unions and frequent category shifts. This is evident in marriage records from Cartago, for instance, where church unions between mestizo partners went from 18 percent of all marriages in 1738–47 to 78 percent in 1818–22, without a single marriage between a Spaniard and an Indian being registered in the entire period.15 The growth of the mestizo category seems to have reflected not a late-blooming sexual intimacy between Spaniards and Indians, but the increasing geographic and social integration of certain mulattos, pardos, and indios into white society. “Mestizo,” a racial category that was officially sanctioned but not claimed in practice by any social collective, was adopted as a euphemistic reclassification—a sort of de facto, plebeian cédula de gracias al sacar.16

The Royal Pragmatic was meant to prevent just this sort of convergence, to shore up the colonial order by making legal marriage the bulwark against racial straying by men and women of pure or near-pure Spanish descent. In Cuba, where plantation slavery was expanding rapidly in just these years, the Pragmatic was indeed used toward this end.17 But in late-eighteenth-century Costa Rica the nexus of race and production was quite different. When the Pragmatic was issued in 1778, mulattos, zambos, mestizos, and ladinos already outnumbered españoles by 3.7 to one in the province, and a single generation later the figure was nearly eight to one. Poor whites participated alongside those labeled mulattos and mestizos in the settling of the western Central Valley, and all faced a similar panorama of hard toil and insecure land rights. In Cuba the institution of slavery stood between poor whites and the black majority. In Costa Rica self-purchase and informal manumission had reduced the total of slaves to a hundred at most, and race was ever less salient as an axis of difference among the gente del común. Conjugal households, not plantations, structured rural production. In the words of one man facing eviction, “I have a cane field, trapiche [cane grinder and boiling house], house, plantains, fruit trees, and cattle . . . all of which I have planted with the sweat of myself and my woman and my children.”18 The male-headed nuclear family the petitioner described was entirely consistent with the kin forms promoted by church and state, and perhaps two-thirds of households were united by the sacrament of marriage.19

Peninsular authority in Central America ended with a whimper rather than a shout. Disenchanted with the liberal Cortes governing Spain in the wake of the Napoleonic invasion, and wary of the social unrest accompanying independence movements to the north and south, Guatemalan aristocrats declared the provinces independent in 1821. Absorbed by elite rivalries and struggles for primacy among highland towns, the new national governments of Central America devoted even less attention to the Caribbean lowlands than late colonial officials had. States pressed territorial claims in treaty negotiation...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Illustrations, Figures, and Maps

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter One: The Evolution of Family Practice in Jamaica and Costa Rica

- Chapter Two: Sojourners and Settlers

- Chapter Three: Las Princesas del Dollar

- Chapter Four: Compañeros

- Chapter Five: Facety Women

- Chapter Six: Men of Respect

- Conclusion

- Appendix

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index