![]()

Introduction

A Community History

The Ju/’hoan San of Nyae Nyae are a people who today see themselves as an indigenous minority who have basic human rights as citizens of the southern African country of Namibia. This book describes the process by which they have developed that perspective. It examines the wide array of changes that have occurred in Nyae Nyae, looks at the responses that the Ju/’hoansi have had to these challenges, and describes how they have been able to become political actors on the national and international stage, seeking greater recognition of their human rights, their right to development, and their right to participate in public policy decisions.

The Ju/’hoansi today are citizens of Namibia, a relatively new nation in Africa, which achieved its independence in March 1990. Namibia is located in southern Africa, with the Atlantic Ocean to the west, Angola to the north, Botswana to the east, and South Africa to the south (see map 1). Namibia also shares a border with Zambia along the north of the Caprivi Strip. Covering an area of approximately 824,000 square kilometers, Namibia is slightly more than half the size of the American state of Alaska. As a country, Namibia is heavily dependent on the mining industry, agriculture, fishing, and tourism, as well as on receipts from the Southern African Customs Union (Republic of Namibia 2006; World Bank 1992, 2008). Today, it is a member of the Southern African Development Community (SADC). Like all of the countries of southern Africa, Namibia has a complex history, some of which is outlined in this book.1

Map 1 Namibia, Botswana, and adjacent nations

Namibia is one of the most arid countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Rainfall varies between 25 millimeters per year in the Namib Desert in the west to 700 millimeters per year in the Caprivi region in the northeast. Water is a limiting factor in many areas, and the variability in the timing, distribution, and amounts of rainfall has to be considered carefully by planners and by local people. Namibia's only perennial rivers flow along portions of its northern and southern borders, the Cunene River in the north and the Gariep (formerly the Orange) River in the south (see map 2). The people, wildlife, and livestock of Namibia are almost entirely dependent upon ephemeral rivers, surface water after rains, small springs, and groundwater (Chenje and Johnson 1996; Jacobson, Jacobson, and Seely 1995). The water table in the country has dropped significantly in some areas over the past several decades, in part because of water extraction to supply human domestic needs, livestock, agriculture, towns, industry, and mining. According to Gleick (2006: 241, table 3), 20 percent of Namibia's population lacks access to safe drinking water. Obtaining access to sufficient land and procuring adequate water supplies to meet basic needs have been two of the major challenges facing local people in Namibia.

From an ethnographic standpoint, Namibia is a diverse country, with about 28 different languages spoken and a large number of ethnic groups, some of them, such as the Ovambo, quite sizable. Some of the groups in Namibia, including the San and the Nama (Khoekhoe), consider themselves to be indigenous to the country. While a number of these ethnic groups have been investigated by social scientists (Gewald 1999; Hahn, Vedder, and Fourie 1928; Malan 1995; Schapera 1930), a significant amount of attention has been paid to the Ju/’hoan San, who in the past were sometimes labeled the !Kung.

Map 2 Namibia and its river systems

The Ju/’hoan San have been the subject of anthropological study and interest for over 50 years (Barnard 2007: 53–58; Biesele 1986; Gordon and Douglas 2000; Hitchcock 2004; Lee and DeVore 1976; L. Marshall 1960, 1961, 1976; Thomas 2006: 48–51; Wiessner 1977, 2002). As a result, the Ju/’hoansi are some of the best-known and most thoroughly documented indigenous peoples on the planet. In some ways, they are considered southern Africa's “model people” (Jenkins 1979). James Suzman (2001b: 39) points out that the Ju/’hoansi have received a disproportionately greater amount of attention relative to their numbers than any other group in Namibia. He goes on to note: “This high profile is also reflected in the extent of non-government organization activity in the area” (ibid.).

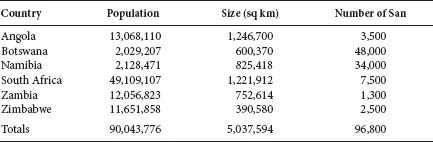

The Ju/’hoansi are one of a number of different San groups in southern Africa.2 There are approximately 100,000 San living in six southern African countries today (see table 1). The San population is made up of a diverse set of self-identifying groups who speak a wide variety of languages and who exhibit both similarities and differences in customs, traditions, economic practices, and histories.

There is much debate in the anthropological and linguistic literature over the most appropriate term to be used for Ju/’hoan peoples (Barnard 1992, 2007; Lee 1976, 1979a). The term “!Kung” is actually the name of a San language that is closely related to the Ju/’hoan language. It is used primarily to refer to !Xun who reside in the north of Namibia and southern Angola, with some members living in what is now Tsumkwe District West (formerly Western Bushmanland) (Barnard 1992: 39, 45–46; Pakleppa and Kwononoka 2003; Suzman 2001b: 38–39, 42). The people with whom we deal in this book prefer to be known by the name “Ju/’hoan,” which means true or ordinary people.

Table 1 Number of San in southern Africa

Note: Figures estimated as of July 2010.

Source: Data obtained from the Working Group of Indigenous Minorities in Southern Africa (WIMSA).

The Ju/’hoansi are northern San whose language contains four click consonants, a feature of great interest to linguists (Crystal 2000: 56–57). There is also considerable interest in the Ju/’hoansi and their neighbors on the part of geneticists, biological anthropologists, and demographers (Howell 2000; Nurse, Weiner, and Jenkins 1985; Tishkoff et al. 2007, 2009; Vigilant et al. 1989). The Ju/’hoansi exhibit a number of interesting features, ranging from the ways in which they adapt to their environment, share goods and services, and engage in consensus-based decision-making and conflict management (Lee and DeVore 1976; L. Marshall 1976; Thomas 1958, 1994, 2006).

Estimates of the numbers of Ju/’hoansi vary, depending on the source of the information. In 1979, Lee (1979a: 35, table 1) estimated that there were 4,000 Ju/’hoansi in Namibia and 2,000 in Botswana, for a total of 6,000. Gordon and Douglas (2000: 7) said that there were 7,000 Ju/’hoansi in Namibia, mainly in the Grootfontein, Tsumeb, and Bushmanland (now Tsumkwe) districts. The Summer Institute of Linguistics volume on world languages, Ethnologue (Lewis 2009), suggests that there are 28,600 Ju/’hoansi in southern Africa, which we believe is an overestimate. The Working Group of Indigenous Minorities in Southern Africa (WIMSA) recently put the number of Ju/’hoansi in Namibia at 6,000 (Axel Thoma, pers. comm., 2007; Joram /Useb, pers. comm., 2007). We estimate that the total number of Ju/’hoansi in Namibia and Botswana today is approximately 11,000 people. We have to admit, however, that this figure is a mere approximation, since getting accurate census data that take into account ethnic identity is a complex process in southern Africa. Southern African governments are reluctant to include questions relating to ethnicity in national censuses, and there are both logistical and methodological difficulties inherent in population censuses. An additional problem is that individuals sometimes shift their identities and do not always give the same answers to questions about their backgrounds.

The Ju/’hoansi represent the second largest group of San in Namibia (see table 2 for a summary of the populations of San in Namibia). The largest San population is the Hai//om, who reside in northern Namibia and whose ancestral territory included what is now Etosha National Park, the largest protected area in Namibia.3 Another sizable population of San in Namibia is the Khwe, some of whom reside today in Tsumkwe District West close to the Ju/’hoansi, and the majority of whom reside in Kavango and Caprivi to the north. Some of the Khwe and the !Xun ex-soldiers and their families opted to go to South Africa with the assistance of the South African Defence Force (SADF) prior to Namibian independence in March 1990.4

Table 2 Populations of San in Namibia

| Group Name(s) | Location | Population Size |

| //Anikwe | West Caprivi | 400 |

| Khwe | West and East Caprivi, some in Tsumkwe District West, Otjozondjupa region | 5,000 |

| !Xun | Okavango, Otjozondjupa regions | 6,000 |

| Ju/’hoansi | Tsumkwe East, Otjozondjupa, Omaheke, Gobabis | 7,000 |

| Hai//om | Oshakati, Uutapi, Tsumeb, Outjo, Etosha National Park, Grootfontein | 11,000 |

| Naro | Omaheke region, Otjinene and Gobabis districts | 2,000 |

| =Au//eisi | Omaheke region, Otjinene and Gobabis districts | 2,000 |

| !Xõó | Omaheke region, Otjinene and Gobabis districts, Mariental region, Hardap district | 300 |

| |’Auni | Mariental region, Hardap district | 200 |

| N|u (/Nu-//en) | Mariental region, Hardap district | 100 |

| Total | | 34,000 |

Source: Data compiled from reports and documents on file in the WIMSA library, the Namibia National Archives, the library of the Kuru Family of Organizations, and published literature (e.g., Gordon and Douglas 2000: 7; Suzman 2001b: 3, table 1.1).

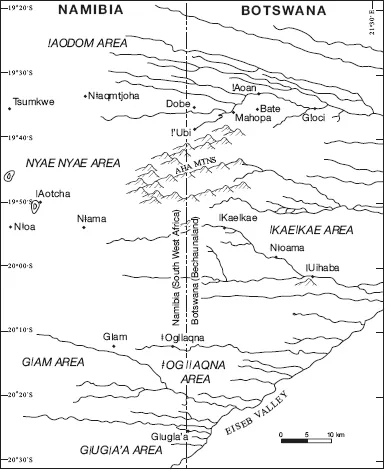

The area where the Ju/’hoansi reside today stretches across the Botswana-Namibia border from Tsumkwe and areas to the west into Botswana as far as Gomare, Tsau, and Sehitwa near the Okavango Delta in the east (see map 3). There are Ju/’hoansi residing in areas in the southern territory of Nyae Nyae, including the Omaheke portion of the Gobabis farms region of eastern Namibia (Suzman 1999: xxii–xxvi; Sylvain 1999, 2001) and the Grootfontein farms to the west (Suzman 2001b: 12–13). Ju/’hoansi also live in some of the towns of Namibia, including Grootfontein, Otjiwarongo, and Windhoek. The majority of the Ju/’hoansi reside in the Kalahari Desert region of northeastern Namibia and northwestern Botswana. Thus, Ju/’hoansi are, like many indigenous groups around the world, transboundary peoples, having to deal with all of the social and political complexities that that status implies.

Map 3 The Nyae Nyae and /Kae/kae areas in northeastern Namibia and northwestern Botswana

Anthropological Research on the Ju/’hoansi

While anthropological observations were made about the Ju/’hoansi and their San neighbors in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Gordon and Douglas 2000; Guenther 2005; Schapera 1930), it was not until the 1950s that serious, long-term, and detailed ethnographic work was carried out among Ju/’hoan populations. In 1950, Laurence Kennedy Marshall retired as president of Raytheon Corporation in the United States. As Lorna Marshall (pers. comm., 1990) noted, retirement provided her husband with an opportunity to pursue his interests. In addition to spending time with his family, one of the things that he wanted to do was to sojourn in Africa, which he had read about extensively as a child. Stories about the “lost city of the Kalahari” had particularly intrigued him. Marshall approached the Peabody Museum at Harvard University to see if there was any interest in carrying out an expedition to the Kalahari Desert of southern Africa. J. O. Brew, the director of the Peabody, said that, if they were to go to the Kalahari, the Marshalls might spend some of their time looking for “wild Bushmen,” meaning those people who lived solely by hunting and gathering.

In 1950, Laurence and his son John made their first trip to the Kalahari. They heard at /Kae/kae in Botswana that there were groups farther to the west who were living independently of other groups and who were foraging. In 1951, the Marshalls, including Laurence and his wife Lorna, son John, and daughter Elizabeth (now Elizabeth Marshall Thomas), set off for what is now Namibia. Their objectives were to visit places that had “been relatively little explored” (Thomas 2006: 46, 48), to establish contact with people living in remote areas (L. Marshall 1976: 2–3), and to learn about the hunting and gathering way of life.

Doing fieldwork in South West Africa in the 1950s was a complex undertaking. At the time that the Marshalls worked in the Nyae Nyae region (1951–1961), there were incidents of local people being captured and pressed into service in the mines or on cattle posts, ranches, or farms. In some cases, the farmers who came into the Nyae Nyae area persuaded local Ju/’hoansi to join them and took them away to their farms (L. Marshall 1976: 60). The Ju/’hoansi were also faced with the prospect of Herero and other groups moving into the Nyae Nyae region and establishing cattle posts. Some of the Ju/’hoansi were only too happy to work for the Herero because they were able to get access to milk and meat and sometimes were given gifts of food, clothing, and tobacco. In 1957, when Laurence Marshall again visited the Nyae Nyae area, he heard more details about the ways in which some of the Ju/’hoansi were being treated on the cattle posts, and he reported the matter to the South West African authorities. In response, the South West Africa Administration (SWAA) sent police patrols to the Nyae Nyae region, and the officers convinced the Herero to return to their homes in Botswana (L. Marshall 1976: 60; Lorna Marshall, pers. comm.).

The Marshall family expeditions had a profound impact on the Ju/’hoansi, providing not only much entertainment and a periodic source of food and income, but also, according to Ju/’hoansi informants, a more positive sense of themselves. The expeditions to the various pans in the Nyae Nyae region led to increased numbers of local visitors in the places where they stayed. The larger numbers of people in the camps had both costs and benefits. On the cost side, local people had to go farther to get sufficient bush food to sustain themselves, except when they were being provisioned by the Marshalls. There were also more conflicts in the camps than when the camp sizes were smaller and there were fewer people from different bands living together, according to the Ju/’hoansi. On the benefit side, the greater degree of sedentism meant that there were more opportunities for people to engage in social interactions, for marriages to be arranged, and for exchanges of goods and services to occur, not to mention the possibilities afforded by the presence of the Marshalls and their co-workers.

The Marshalls did not have an easy time carrying out their work in South West Africa. There were logistical difficulties, such as vehicle problems (e.g., broken springs and overheated radiators) and the limited availability of water. Lorna Marshall says that she reported on the arduous nature of the journeys into the Nyae Nyae region because she believed that the grueling travel conditions were “so important a protective factor for the !Kung maintaining their way of life” (L. Marshall 1976: 13).

At the time of the expeditions, the Ju/’hoansi and other San in Namibia were under the administrative oversight of the South African Department of Bantu Administration and Development (L. Marshall 1976: 13). The South West African Native Affairs Administration Act of 1954 laid out the bureaucratic structure under which the Ju/’hoansi and other Namibian “native” populations fell. Essentially, the Ju/’hoansi were at the bottom of a several-tiered bureaucratic and socio-economic system in South West Africa. They had no right to self-representation; they had no leaders who were recognized by the SWAA; and they had no say over what could be done with regard to the land that they occupied and the water sources on that land.

The pace of change in the Nyae Nyae region began to quicken during the time of the Marshall expeditions in the 1950s (L. Marshall 1976: 13–14, 60–61). The Witwatersrand Native Labor Association began recruiting Ovambo and Kavango men for mines in the area just to the north of the Nyae Nyae region, and some of the mine labor recruiters visited the Nyae Nyae area, following the tracks of the Marshall vehicles (Lorna Marshall, pers. comm., 1990).

The Settlement at Tsumkwe

The next episode in Ju/’hoan history, from 1959 to the late 1970s, was characterized by several South West African government decisions regarding land use and zoning and the establishment of administrative infrastructure and management systems. These decisions had a series of ever widening social and economic implications for the residents of the area. The administrative center for Nyae Nyae, called Tsumkwe, was established in 1959. The center was meant to be a location of permanent and sedentary resettlement for the Ju/’hoansi, a way of incorporating them into “modern” life. The South West African government promised the Ju/’hoansi jobs, agricultural training, and access to medical care. It also encouraged them to come to Tsumkwe by offering them food and water.

Infrastructure development at Tsumkwe included drilling a borehole, preparing land for agricultural fields, and setting up a police station, a store, and a housing scheme (J. Marshall 1989: 46–49; L. Marshall 1976: 73). Paid jobs were made available, but only for a few people. The high population density and low rate of employment, combined with the availability of alcohol at the store, resulted in a whole series of social, economic, and health problems. The degree to which people in Tsumkwe could depend on wild foods declined. Resources were depleted relatively quickly in the vicinity, and because the people were now sedentary, these resources were not replenished as would normally occur when a group would move elsewhere in the annual mobility pattern. The diet deteriorated as people became increasingly dependent upon maize meal rations provided by the administration and foodstuff purchased from the local store. When people refused to share the few resources that they were able to obtain, reciprocity systems were disrupted and social tensions increased. Rape, domestic abuse, and interpersonal violence were common in Tsumkwe.

According to the Ju/’hoansi, life in Tsumkwe was characterized by poverty, ill health, apathy, and social dissatisfaction. Tensions increased to the point that fights would break out fairly frequently. The mo...