eBook - ePub

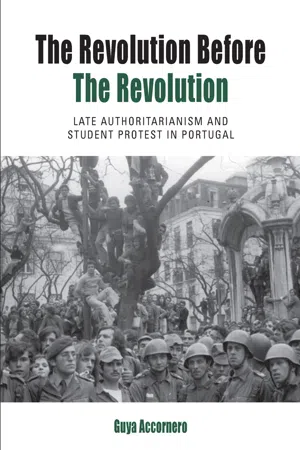

The Revolution before the Revolution

Late Authoritarianism and Student Protest in Portugal

- 186 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Revolution before the Revolution

Late Authoritarianism and Student Protest in Portugal

About this book

Histories of Portugal's transition to democracy have long focused on the 1974 military coup that toppled the authoritarian Estado Novo regime and set in motion the divestment of the nation's colonial holdings. However, the events of this "Carnation Revolution" were in many ways the culmination of a much longer process of resistance and protest originating in universities and other sectors of society. Combining careful research in police, government, and student archives with insights from social movement theory, The Revolution before the Revolution broadens our understanding of Portuguese democratization by tracing the societal convulsions that preceded it over the course of the "long 1960s."

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Revolution before the Revolution by Guya Accornero in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Two Decades That Shook the World: 1956–1974

Old Structures and New Conflicts

From Khrushchev to the New Left

The analysis of the Portuguese student movements throughout the 1960s and 1970s cannot ignore the formation of a left more to the left than the Communist Party which had, up until this date, represented the main reference point for the forces of opposition to the New State. In fact, the birth of a new left and its convergence with the student and youth movements was a common feature of the Western world as of the early 1960s, without major distinctions between the countries governed by authoritarian regimes and the democratic ones. Up to the end of the 1950s, in the imagery of militants and sympathizers of Western communist parties, the Soviet Union constituted, in fact, a symbol of hope in the actual achievement of an egalitarian society. In spite of this prestige, however, the accusations of excessive centralization and rigidity directed at Western communist parties, often coming from their own members, were not rare.

In this context, 1956 represents a fundamental year. The declarations of the new Secretary, Nikita Khrushchev, with the denouncement of Stalinism, at the XX Congress of the CPSU, had a profound effect on Western communist parties. The Soviet Union no longer represented socialist utopia while Western communist leaders were accused of having concealed and falsified the truth. The critique necessarily involved the actual inner functioning of parties as well as the attitude they maintained after the XX Congress.

On the other hand, the new course of the Soviet Union stipulated that Western communist parties should accompany ‘the Soviet inflexions unhesitatingly’ (Pacheco Pereira 2005: 345), inflexions that tended towards establishing a climate of ‘peace in the world’, correcting aspects that defined the sectarianism that had dominated the previous period. The interweaving between international and local elements emerges starkly at this point, since, while it may be true that the long waves of the XX Congress were a determinant in the choices of Western communist parties, it is also necessary to highlight that they were inserted in dynamics specifically linked to the national events of the 1950s. An example of such is the case of the Partido Comunista Português (Portuguese Communist Party, PCP), whose main leaders, including Álvaro Cunhal, had been in prison since 1949. As demonstrated by one of the principal researchers of the PCP, José Pacheco Pereira, this condition led to a series of profound consequences in the history of the party over the following years. Hence the effects of the Khrushchev era and of the successive, and in part consequent, Sino-Soviet conflict, occurred under this scenario of internal tensions, which found a provisional solution only in 1961, when, a little after the Peniche prison escape of January 1960 and during the meeting of the Central Committee when he was appointed Secretary of the PCP, Cunhal declared that it was necessary to suppress this tendency defined as ‘anarcho-liberal’ and responsible for a ‘right-wing deviation’.

Knowledge of the critical situation of the party was hardly secondary in determining the urgent need to escape from prison and embark on the immediate restructuring of the party’s guidelines. The new course was later confirmed in 1965 during the VI Congress of the PCP held in Kiev, with Álvaro Cunhal’s presentation of the plan called ‘Rumo à Vitória. As tarefas do partido na revolução democrática e nacional’ (‘Route to Victory. The Party’s tasks in the democratic and national revolution’), already discussed with the Central Committee in 1964. This debate, in which the party was immersed during the early 1960s, in the meantime coincided with the eclosion of the Sino-Soviet conflict that hit the PCP at a critical moment of its history (Pacheco Pereira 2008: 127). Thus, at the same time that the new Central Committee of the PCP managed to re-establish a certain consensus within the party in renewing objectives and strategies between 1963 and 1964, new dissidence was sparked by the Sino-Soviet conflict and coagulated around Francisco Martins Rodrigues, a member of the Executive Committee of the Board. Having been imprisoned with Cunhal in Peniche and had escaped with him in 1960, he was thus expelled from the party and founded the first pro-Chinese organizations in Portugal, the Comité Marxista Leninista Português (Portuguese Marxist–Leninist Committee, CMLP) and the Frente de Acção Popular (Popular Action Front, FAP).

These episodes will be explained in further detail below. At this stage, it is sufficient to observe how the new strategy of political fight, of correction of the ‘right-wing deviation’ – theorized by Cunhal back in 1961 and restated in 1965 – was not completely independent from this ‘crossing over’ to the left by an explicitly revolutionary group which criticized the PCP, above all, for its moderation and attitude of waiting. In fact, as shown by Pacheco Pereira:

In the PCP’s internal debate, the full revision of the ‘right-wing deviation’ line, which in many aspects represented Khrushchev’s line after the XX Congress applied in Portugal, the substance of this rectification theoretically placed the PCP and Cunhal much closer to the Chinese theses than those of the Soviet approach. Cunhal was thus forced, at the same time as he fought against this tendency in Portugal as a ‘right-wing deviation’, to approve it as the line of the international communist movement. (Pacheco Pereira 2008: 128)

This sparked the beginning of this competition to the left which would lead, by the end of the decade, to the pulverization of the Marxist world and to the gradual loss of consensus of the PCP in the more radical wings of the opposition. Adopting Leninist language, Cunhal was to react to this situation, by now in 1970, accusing the ‘leftists’ of being ‘renegades’ and ‘adventurers’, especially due to the fact of not considering that the ‘fight of the masses’ was important to topple the regime and, therefore, of ‘showing contempt for’ the organization and political conduct aimed at creating consensus among the population (Cunhal 1970).1

The Soviet World and China

The most explosive consequences of the criticisms pointed at Stalinism by Khrushchev were immediately felt in Eastern Europe, above all in Hungary and Poland, where the report of the new Secretary of the CPSU gave rise to the illusion that the hegemony of the Soviet Union over its satellites could decline or even end completely. In Poland, it was in particular the workers supported by the Catholic Church who led the protests, which culminated in the great Poznań uprising in June 1956. The strike was suppressed by the intervention of Soviet troops, but the insurrection continued during the summer, having become a widespread movement of protest that extended to various sectors of society, which is now known as the Polish October. Instead of facing a difficult military repression, the leaders of the USSR decided to make a change in the vertices of the Polish party and government, favouring the rise to power of the former Secretary of the Polish Communist Party, Władysław Gomulka, who, imprisoned in 1951, had been rehabilitated following the XX Congress. Gomulka promoted a policy of cautious release of liberalization and partial reconciliation with the church, albeit never placing in question the alliance with the Soviet Union or the terms of the Warsaw Pact.

The far better known crisis in Hungary initially followed an almost analogous course, but culminated in a much more dramatic outcome. In this case, the leaders of the revolt were above all students and intellectuals, whose protests, during the month of October, ended in a real insurrection, also involving broad sectors of workers. Workers’ committees autonomous of the official organizations were created in all factories. Imre Nagy, a communist of the liberal wing, who had already been expelled from the Communist Party, was called upon to head the government. When, on 1 November, Nagy announced the country’s withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact, the Secretary of the Communist Party, Kadar, invoked Soviet intervention. Soviet Army troops occupied Budapest and violently repressed the resistance that had formed against them. A few months later, Nagy was executed, and Kadar took over the running of the country. The Soviet intervention, which appeared as a radical dashing of the hopes born of the de-Stalinization process, caused protests and denouncements at an international level, giving rise to real crises of conscience among communists all over the world, already affected by the trauma of the Khrushchev report.

Hence, while it is true that in the immediate term, concerning relations of force, the USSR managed to maintain control over its satellite states, it is also true that the experiences of Poland and above all Hungary marked the onset of a loss of consensus on the Soviet Union and the actually existing socialism among the weakest sectors of society, which had up to then always represented a model of the ideal society. On the other hand, the de-Stalinization was not only contested by the right wing, due to its betrayal of liberalizing promises, but also by the left wing, due to being considered a betrayal of the path designed by the fathers of communism, Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin and, finally, Mao. The factions that upheld this critique thus easily turned towards China, which began to represent the new model to be followed by the new Marxist–Leninist groups, composed especially by young people and students and, in Portugal, also by young deserters and conscientious objectors to military service in the Colonial War.

The Sino-Soviet conflict deepened these cleavages. This conflict was essentially based on State rivalry and political–ideological divergences, linked both to international strategies and internal politics. As emphasized by Pacheco Pereira: ‘Both the CPSU and the CPC [Communist Party of China] were parties in power, commanding over countries with overlapping zones of influence, with distinctive national policies, each with their own particular weight in the communist movement, and each considered that they were entitled to define their own international policy’ (Pacheco Pereira 2008: 10). Therefore, while the USSR proposed the maintenance of a bipolar world order, China contested the international status quo, in particular by supporting the cause of revolutionary movements all over the world, with the intention of representing a guiding model to developing countries against imperialism. Underlying this tendency was the Maoist idea that the revolution could be launched from countries of the third world; in other words, that a certain level of industrial development was not necessary for a revolution. It would be the rural masses, trained in guerrilla warfare, more than the proletariat, who would represent the fundamental actors of the revolution. This position – while it also showed evident motivations linked to its raison d’état, dictated by the interest in contrasting with the domain of the two superpowers (USA and USSR) and giving China a relevant role in the international context – had a deflagrating effect in the factious midst of Western Marxism, supplying an ideological baggage of the new utopias assumed and disclosed by the tiny Marxist–Leninist cells that began to sprout all over Europe. However, as shown above, while these dynamics exacerbated the process:

The prehistory of the pro-Chinese and pro-Albanian groups in countries of Europe, America, Australia and New Zealand date from the XX Congress of the CPSU and of de-Stalinization, processes whose impact created tensions and resistance within communist parties … These tensions led to dissidence of groups which evolved to other forms of communism, to the left and to the right, or to non-communist or radical socialist platforms, with progressive loss of communist identity. (Pacheco Pereira 2008: 65)

The Western World and May 1968

While in the Soviet world there was an opening of contestation of a liberalizing nature regarding the political and social structures of the existing socialism, in the Western world the contestation was in particular turned against capitalism and the inequalities that it was causing in the midst of the allegedly well-run welfare society. Moreover, as noted above, in more recently democratized countries, contestation was likewise directed against the authoritarian elements that also existed in democratic contexts, linked in particular to harsh measures in the management of public order and to aspects, endorsed or not, of social exclusion. The contestation of the capitalist model, not only economic but also cultural, embodied by the consumer society appeared initially, especially in the Anglo-Saxon world, under the guise of an absolute rejection of the industrialized society. This formed the underpinnings for the proliferation of hippy communities and later the creation of an alternative culture, into which flowed concepts such as conduct of non-violence, eastern religious philosophy, drug consumption and the messages of new music. Later, the youth insurrection would take on more politicized forms and find its driving centres at universities, where the education of the masses had given rise to a more numerous student body, and one that was more socially vociferous than ever before. Also in this case, the phenomenon began in the United States, where the mobilization – initiated with the occupation of the University of California, Berkeley in 1964 – was interwoven with the protests against the Vietnam War and the civil rights movement.

Following 1966–1967, and with its peak in 1968, the student uprising spread to Japan and the largest European countries, where it took on more radical and ideological forms. One of the principal unifying elements was, as we have seen, not only the fight against authoritarianism, considered to be a distinctive aspect of advanced industrial societies, but also the mobilization against ‘American imperialism’, especially against the intervention in Vietnam. In Germany, the student unrest was particularly concentrated against the repressive measures of the grand coalition government and against the major press, controlled by the right, giving rise to political organizations that defined themselves as extra-parliamentary. In France, the coagulation among the different movements of the extreme left, which sought to combine the traditional revolutionary fervour with new forms of anti-authoritarian fight, in line with the situationist movement, led to the most famous episodes of the entire season of student uprisings, those of May 1968.

The Italian Case and the Hot Autumn

Italian students had been at the genesis of an outbreak of mobilization back in 1960, when, together with various sectors of workers, they contested the formation of a single-colour Christian-Democrat government which had the external support of the Movimento Sociale Italiano (Italian Social Movement, MSI), a party that was the direct heir of fascism and up to this time officially excluded from the political arena. Merely fifteen years after the end of the regime, this choice was considered offensive to the new democratic institutions and a betrayal of the constitutional values expressed by all the forces that had participated in the resistance fight. The protests that emerged were violently repressed, and nine young students, all aged between 18 and 21, were shot dead by the police during the demonstrations. The student protests resurged in Italy particularly from 1967 onwards, leading, in this case, to the occupation of numerous universities and to major demonstrations in the streets, as well as, once again, violent confrontations with the police.

At this stage, the Italian uprising incorporated issues that were already present in the movements of other countries (anti-imperialism, opposition to the Vietnam War, anti-authoritarianism, anti-capitalism), but also showed specific characteristics in terms of a strong Marxist and revolutionary ideological basis, rooted firmly in the ‘workerist’ tradition. The student movement grew in the fight against academic authoritarianism and the principle of school selection, but assumed an increasingly more hostile opposition in relation to the entire capitalist system and bourgeois culture in general (Ortoleva 1988; Agosti, Tranfaglia and Passerini 1991). The criticism levied at the bourgeois society was transformed into a rejection of traditional political conduct, including historical left-wing parties, the exaltation of grassroots democracy based on collective decision making and egalitarianism. This search for new forms of conducting politics was accompanied, in many cases, by a revolution in sexual behaviour, and in personal and family relations.

Following the autumn of 1968, the student movement identified the proletariat as its preferred and target partner. The search for this connection derived not only from the influence of the intellectual groups which had for some time assumed workerist positions, but also, more generally, from the presence of a strong Marxist tradition which had characterized the culture of the Italian left throughout the entire post-war period. Workerism was also a distinctive feature of the political groups that emerged between 1968 and 1970 in the wave of the student movement, and that, as in the German case, began to call themselves extra-parliamentary. Among other cases, we recall the ‘Potere Operaio’ (Workers’ Power), ‘Lotta Continua’ (Continuous Struggle) and ‘Avanguardia Operaia’ (Workers’ Vanguard) (Grandi 2003; Cazzullo 2006).

The attention given to the working classes by Italian students coincided with an intensive period of struggle by industrial workers which, having started in early 1969 on the occasion of a series of contractual renewals, culminated in the autumn of that year. The protest had begun almost spontaneously in various large factories in the north, with its main protagonist being the figure of the so-called mass worker – in other words, the unqualified worker, often an immigrant from the south and, therefore, upon whose shoulders the working conditions and lack of adequate social services weighed most heavily. On the other hand, while in many cases the workers from the north already had a strongly structured political education given by the Confederazione Generale Italiana del Lavoro (Italian General Confe...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Chapter 1. Two Decades That Shook the World: 1956–1974

- Chapter 2. The First Protest Cycle: 1956–1965

- Chapter 3. ‘The Marcelo’s Spring’ and the Opening of a Second Protest Cycle

- Chapter 4. Protest Cycle or Permanent Conflict?

- Chapter 5. The Demise of the New State

- Conclusions. Social Movements and Authoritarianism: A Paradoxical Relationship

- Bibliography

- Index