![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

Roy Ellen

Background

The 1990s witnessed a growing acknowledgement world wide of the importance of local ecological knowledge in the context of food security and sustainable development (Warren, Slikkerveer and Brokensha 1995; Sillitoe, Bicker and Pottier 2002; Pottier, Bicker and Sillitoe 2003; Bicker, Sillitoe and Pottier 2004). Much has been written of how this knowledge can help us avoid the problems associated with top-down development strategies, how it can provide cheap and appropriate solutions in the absence of modern health-care delivery systems and the drugs on which they depend, and how it can help conserve local habitats and maintain genetic diversity. It is argued that local knowledge is by definition culturally relevant, improving rural livelihoods, nutrition and general well-being, while encouraging a more rational use of natural resources. Moreover, it is said to strengthen local institutional capacity, leaving a general capital surplus for financing other initiatives (Alcorn 1995: 1). Less attention has been paid, however, to the particular role local knowledge might have in providing a set of responses to which populations may resort in times of political, economic and environmental instability, or to how traditional knowledge strategies are used as responses to specific natural, economic and social disasters (but see Walker 1995).

The period 1996–2004 in island southeast Asia presents an instructive test case for understanding how coping mechanisms based on essentially local strategies might work, as the period has witnessed multiple socio-economic and ecological crises following on from – for the most part – a period of sustained economic growth and modernization (approximately between 1965 and 1996), which itself provided the assumed conditions for the erosion and neglect of traditional knowledge. In an attempt to plug this gap, this book explores how the decline of traditional environmental knowledge that has accompanied modernization in island southeast Asia has been challenged by recent natural disasters, economic problems and political conflict, and how the use of traditional knowledge, together with its innovative combination with new kinds of knowledge, continues to enable communities to manage the crises they face. The book, therefore, is concerned with the creation, maintenance, modification and transmission of ecological knowledge, and increasingly with the hybridization between traditional and scientifically based knowledge, but in the context of those local forces of instability that shape it. Although it focuses on a recent period in the history of island southeast Asia, there has been a continuous record of environmental and socially induced perturbation throughout its documented history and of local responses to this. While these latter have been constantly adjusting to new circumstances, they have evolved in their general principles over the long term. For this reason their understanding inevitably merges with general anthropological analyses of cultural and population adaptation.

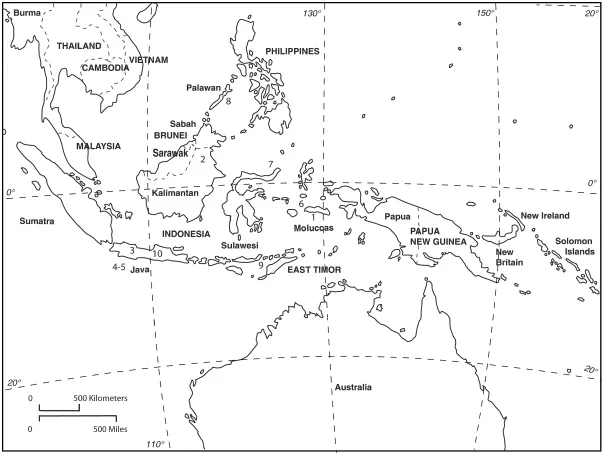

Figure 1.1. Island Southeast Asia, showing location of case studies discussed in text. Numbers refer to chapter. 1, Nuaulu, south Seram; 2, Penan and Kenyah, east Kalimantan; 3, Kasepuhan, west Java; 4-5, Baduy, west Java; 6, Buano, central Maluku; Minahasa, north Sulawesi; 8, Batak, Palawan; 9, Oeucusse, East Timor; 10, Merapi, central Java.

The region selected for examination comprises the modern nation states of Malaysia, the Philippines, Indonesia, Brunei Darussalam and East Timor (Figure 1.1). Indonesia, inevitably, dominates the discussion, occupying as it does 75 per cent of the territorial space of the countries listed and, at 208 million, providing 68 per cent of the total population. Although no specific chapter is devoted to Brunei, Ellen (Ellen and Bernstein 1994, Bernstein, Ellen and Bantong Antaran 1997) has research experience in this country and some reference will be made to the situation there later in this introduction. Of the vast expanse of Indonesia, only Papua (Western New Guinea) is excluded, on biogeographic grounds, having more in common ecologically and culturally with the rest of Melanesia. The area covered, therefore, is what geographers, anthropologists and historians generally describe as ‘island (or archipelagic) southeast Asia’, an area that displays a high degree of homogeneity in terms of overall topography, climate, ecology, subsistence systems, languages and cultural histories, when compared with the areas surrounding it, and certainly when compared with the more encompassing and typologically more problematic notion of ‘southeast Asia’ (Fisher 1964: 3–10). The older term ‘Malaysia’ (or, in botany, ‘Malesia’: van Steenis 1948) and ‘Indo-Malaysia’ (Bellwood 1985) are sometimes used to describe the same area, though are not used here to avoid confusion with the nation state of Malaysia.

Whilst the last fifty years of the colonial period and the first years of independence in the states now comprising island southeast Asia can be arguably typified as a period of stability and steady improvement in the theoretical ability of central government and various agencies to manage the environment, sustained economic growth and modernization during this time were not uniform across the region. The precolonial and colonial periods were typified by intermittent environmental hazards and disasters, whether of seismic, volcanic, climatic or biological origin. But in virtually every case these were magnified through human patterns of settlement, land use, social organization and economy. Throughout the nineteenth century the Dutch in Indonesia were unable to control the cycle of crop failure, famine and flood in Java, and before 1930 bad harvests were routinely followed by famine, cholera and other epidemics, which resulted in low population growth (Donner 1987: 32, 54). The ‘new environmental history’ of Indonesia has provided ample evidence for a continuous long-term experience of environmental perturbation, even away from the great agrarian centres (e.g. Knapen 2001).1 In many cases the vulnerability to environmental hazard was induced by the advantages of living in certain locations. Volcanism, which was so often a catastrophe, was compensated for by the clear benefits that volcanic soils provided for local people, whether cattle keepers around Gunung Merapi or nutmeg producers on the Banda islands. And, while seismic disturbances were causally independent of human inputs, the food and water shortages that resulted were magnified by patterns of human landscape change, cultivation and domestication.

But unlike the arid lands of Africa and mainland south Asia and the densely populated lands of south and east Asia, the humid tropics of island southeast Asia have often been perceived as sharing a fundamentally benign human ecology, one historically dominated by rainforest, characterized by slight seasonal fluctuations in temperature and rainfall, and where levels of precipation encourage the rapid growth of crops and other edible vegetation. In such a region, the non-human preconditions for famine generally appeared not to be obviously ecologically endemic, and the instability that gave rise to intermittent hazards arose in large part from the inconvenient presence of the interfaces between the Indo-Australian, Philippine and Pacific tectonic plates (Whitten, Soeriaatmadja and Afiff 1997: 90–91), from factors emanating from a dynamic and emerging social system, or from socially mediated environmental factors. There were exceptions to this ecology, of course, such as challenging soils and topographies, but in many places long-term co-evolutionary processes had resulted in anthropogenic landscape transformation that had allowed local populations to manage these disadvantages. The main environmental handicaps lay in the dry areas of east Nusa Tenggara and Timor, and in Madura and Lombok; and it is hardly surprising that it is for these areas where the colonial records indicate repeated crop failures and drought (Ormeling 1956, Donner 1987: 9–10, 25, 181). In addition, it was, paradoxically, the very capacity of the humid equatorial rainforest environment to be ecologically, and therefore economically, productive that encouraged, over time, patterns and densities of human settlement and agricultural intensification that destabilized these environments and made them more vulnerable to resource shortages. Under colonial conditions, these vulnerable areas tended to be the same as those in which European rulers sought to maximize surpluses and where the local response, given the proximity to carrying capacity, was what Geertz (1963) has famously called ‘agricultural involution’. Involution involved, in general terms, a kind of specialization within the context of long-term ecological simplification: biodiversity and other forms of ecological diversity declined except for the diversity of focal crops. Thus, under conditions of involution we would expect rice landrace diversity to increase as a way of coping with the uncertainties of intensive production and the risks that these entail in terms of water shortage under irrigation and pest infestation (see Lansing 1991). The modernizing lowland systems under high colonialism and postcolonialism have the characteristics of incremental emergent openness: increasing demands were being made on the local system by the wider system, the market simultaneously simplifying and destabilizing the local system by demanding higher productivity through a more specialized division of labour, and providing a means of reproductive maintenance through the greater emphasis placed on wider system organization, logistical infrastructures and institutions of social control (Ellen 1982: 273). It is these latter features that permitted rapid food transfer when, paradoxically, local systems periodically collapsed due to the very forces that gave rise to the higher productivity in the first place. In contrast, upland societies, with low population densities, less market integration and under less pressure to intensify, were more buffered internally against shortages than lowland societies, maintaining higher levels of diversity of all kinds (Li 1999).

The Modernization Project and the Decline of Local Knowledge

The context of the studies collected together here is the growth, development and modernization of postcolonial states in island southeast Asia, and the way in which these processes have undermined traditional forms of environmental knowledge. The powers, which relinquished control of their colonies and dependencies in island southeast Asia with the independence of, first, Indonesia (1946) and the Philippines (1947), then Malaysia (1957) and finally East Timor (1999), had each moulded them to suit the interests of the metropolitan economies. In some respects, therefore, the problem of development that the newly independent states faced was to create an infrastructure and economic base that served the interests of the new states themselves rather than their erstwhile rulers. And yet, in order to survive in the postcolonial world, they also needed to continue to work within an international market structure that itself was the creature of the late colonial period.

The colonial period had given rise to what Boeke (1966; see also Higgins 1955) controversially described as ‘dual societies’: ones in which there was a capital-intensive growth sector, involving extractive industries, manufacturing and estate agriculture, and an ‘underdeveloped’ subsistence sector. This duality had consequences in terms of the retention of ‘local knowledge’. In the capital-intensive sector the conditions favoured a narrow focus on single resources of strategic commercial importance and the discouragement of traditional knowledge, while the subsistence sector still heavily depended upon it. Indeed, in the context of the involutionary process described by Geertz (1963), the attempt by the metropolitan economy to ensure more surplus from the subsistence sector in Java resulted in increasingly ingenious permutations of local knowledge to maintain living standards and pay taxes, in ever more restricted geographical niches. The discouragement of much local knowledge was also linked to another contentious element of Boeke’s theory, that an ‘anti-growth’ subsistence sector was maintained by a ‘peasant mentality’, by which was understood fatalism, effort minimalization and short-termism (e.g. Alatas 1977). These ideological components had, once functionally inverted, an afterlife in the work of Chayanov, through Sahlins (1972; see also Smith 1979), and Scott (1976), where they become instead virtues, rationally consistent with the expectations of a backward-sloping supply curve in the first case and with the cunning ‘moral economy’ of the peasant in the second. In these theoretical versions we can see both a framework to socially contextualize otherwise semi-detached accounts of traditional technical knowledge and coping strategies, as well as a powerful legitimation that ha...