eBook - ePub

German History 1789-1871

From the Holy Roman Empire to the Bismarckian Reich

- 388 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

During recent years, there has been a noticeable increase in interest in the nineteenth century, resulting in many fine monographs. However, these studies often gravitate toward Prussia or treat Germany's southern and northern regions as separate entities or else are thematically compartmentalized. This book overcomes these divisions, offering a wide-ranging account of this revolutionary century and skillfully combining narrative with analysis. Its lively style makes it very accessible and ideal for all students of nineteenth-century Germany.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access German History 1789-1871 by Eric Dorn Brose in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Geschichte & Geschichte des 19. Jahrhunderts. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

A REVOLUTIONARY CHALLENGE,

1789–1815

The brightly colored houses, steeply angled roofs, and imposing stone ramparts of the Imperial City of Aachen sparkled in the sunlight as the travelers ascended a bumpy road which led westward. Near the Austrian territory of Limburg the coaches turned onto a more comfortable paved highway traversing a ridge. Occasionally, the discussion of the gentlemen inside yielded to silence as they peered reverently through the hedges that lined their way. Below them a collage of red and white farmhouse walls, blue slate roofs, golden meadows, and shady copses stretched southeast to the dark green of the Ardennes and the gray walls of Limburg. Finally they halted for a late lunch at the Gasthof Bel Oeil, appropriately named for the beautiful panorama around it.1

One of the six seated around the inn’s largest wooden table, Joachim Heinrich Campe, hailed from Brunswick, where he pursued journalism and promoted educational reform. As the others returned to the debate that had raged since the previous evening, he busied himself with notes for his travel journal. Campe’s companion, Wilhelm von Humboldt, a gifted young scholar from Berlin, implored his former teacher, Christian Wilhelm Dohm, to listen. That the state’s sole function should be to provide military and police security for the people, as Dohm said, was mistaken. For one thing, policemen and soldiers often endangered a person’s freedom. Secondly, there had to be a place for progressive state institutions and policies in the promotion of prosperity, welfare, and enlightenment. States should proactively facilitate personal growth and enable individuals to realize their fullest capacities.

The older man leaned forward, sensing that Humboldt had mistaken him for an enemy of individualism. Famous for his advocacy of Jewish emancipation and assimilation into society without religious conversion, Dohm believed that governments should promote freedoms and champion rights. But all individual efforts to obtain physical, intellectual, and moral well-being would better succeed without cumbersome and badly conceived state regulations. With manufacture, commerce, education, and morality, only individual initiative made the difference between success and failure. The function of states, therefore, should be limited mainly to security. Humboldt, somewhat more impressed but not entirely satisfied, reclined pensively in his chair.

The mid-summer sun of 1789 began its descent in the western sky as Campe and Humboldt parted company with their friends outside the Bel Oeil. They watched and waved as Dohm’s coach returned to Aachen, standing silently until it became indistinguishable from the hedges on either side. A moment later they got into their coach and headed back onto the highway which, ten days later, would bring them to the revolutionary metropolis of Paris.

Each was drawn for different reasons to the great city that all of Europe had focused on since early summer. Campe could not resist the urge to witness the “stirring victory of humanity over tryanny” and the glorious political achievements of “the new Greeks and Romans.”2 Humboldt was attracted more by the Sorbonne, Notre Dame, and the architectural delights of Paris than its teeming masses and political dramas. Thus the ongoing demolition of the Bastille, a “beautiful medieval building,” saddened him. But the young, sophisticated opponent of state tyranny also appreciated the historic, progressive scene unfolding in the French capital. Six days a week the work crews swung their hammers, hurrying to remove the massive prison and make way for a freedom memorial on the same site. “Yes,” he admitted to his diary, “the destruction of the Bastille was necessary. It was the real bulwark of despotism.”3 Avid defenders of individual rights like Humboldt naturally preferred a freedom memorial to the Bastille.

Caspar David Friedrich’s Ruins of Eldena, 1824–25 [Nationalgalerie, Berlin]

Friedrich often employed ruins as symbols of the old order

Friedrich often employed ruins as symbols of the old order

Notes

1. For a detailed description of the trip to the Bel Oeil, and the conversation there, see Wilhelm von Humboldts Tagebücher, Albert Leitzmann, ed., (Berlin, 1916), 14:90–91, 94; and Joachim Heinrich Campe, “Reise des Herausgebers von Braunschweig nach Paris im Heumonat 1789,” Sämmtliche Kinder- und Jugendschriften (Brunswick, 1831), 24:52–53.

2. Cited in Campe, Sämmtliche Kinder- und Jugendschriften, 24:3; and Thomas P. Saine, Black Bread—White Bread: German Intellectuals and the French Revolution (Columbia, SC, 1988), 23.

3. Wilhelm von Humboldts Tagebücher, 14:120.

Chapter One

GERMANY BEFORE

THE FRENCH REVOLUTION

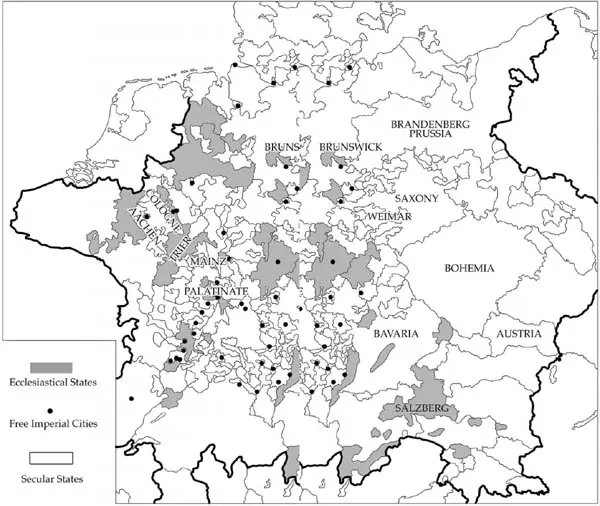

Campe and the others began their journey that historic summer in Brunswick, capital of the Duchy of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, a small but prominent territory located in the north-central portion of the Holy Roman Empire (Reich) of the German Nation. In the Reich of 1789 there were 350 of these “secular” states—that is, territories not ruled by the church—ranging in size from the tiny County of Lippe to large dynastic powers like Prussia, Saxony, Bavaria, and the imperial heartland of Austria. The first week of their trip took them through the Bishoprics of Hildesheim, Paderborn, and Cologne, three of sixty-one church-held “ecclesiastical” territories scattered throughout the western, central, and southern parts of the empire. Within a week, Campe and Humboldt had reached Aachen, one of fifty-one free “imperial” city-states with rights bestowed by the emperor guaranteeing non-interference by secular and ecclesiastical states. The wayfarers also passed through or near several miniscule territories or “estates” presided over by some of the Reich’s 350 “free imperial knights,” petty princes or liege lords whose rights of independence and jurisdiction, like the cities, came directly from the emperor. Before they crossed into France on the twelfth day, the travelers had entered and exited six secular duchies, four bishoprics, one free city, and seven knightly estates—a mere fraction of the 812 largely sovereign political entities of the Holy Roman Empire.

Society and Economy

While in Aachen days before their luncheon at the Bel Oeil, our travelers noted signs of tension between forces of change in society and the old traditional ways. Like many other free city-states, the ancient capital of Charlemagne had long been a citadel of the guilds. These medieval handicraft corporations had controlled urban economic, social, and political life in former centuries. A boy of twelve or thirteen aspiring to the status of master baker, butcher, weaver, or jeweler embarked on this path by paying a fee to enter the master’s household as an apprentice. After years of hard work and training, there followed “tramping days” as a journeyman moving from town to town to work with other masters and acquire more skills. If all proceeded well, a journeyman might complete a “masterpiece” carefully evaluated by guild authorities for proper workmanship. Graduation to guild master remained a tortuous process, however, for journeymen had to purchase the legal right to open shops. These so-called real rights (Realrechte) represented a sizable investment—2,500 florins for an apothecary in Augsburg around 1800, for instance—and usually required considerable negotiation with guild and town authorities who strictly limited the number of licenses.

Licenses gained entrée, however, to the quaint, exclusionary world of the German home towns. Mack Walker’s research has uncovered about four thousand of these guild-run communities, the majority outside of the free cities in a secular or ecclesiastical territory. Rarely exceeding 10,000 inhabitants, they more typically contained only a few thousand people. With the purchase of shop rights came the right to reside and marry in such a town. At home the successful master provided food, shelter, and the emotional security that accompanied survival in an uncertain world. His was a patriarchal household where wife, journeymen, sons, apprentices, daughters, and servants lived and worked in a hierarchy of age and gender. Masters also earned seats on guild councils that regulated the numbers of licenses, the quantity, quality, and price of wares produced, and the social behavior of members. Guild masters usually dominated town government, moreover, passing offices back and forth over the decades among closely related families—a kind of “regime of uncles.”1 It was a much-idealized world of quality workmanship, fulfilling labor, and high status in the community. Thus Christian Wilhelm Dohm wrote in 1781 that the master craftsman “enjoys the present with a pure and perfect joy and expects tomorrow to be exactly like today.”2

Guilds had served aspiring journeymen fairly well during the best economic periods of former centuries, but by the 1780s Dohm’s idealistic characterization no longer rang true, mainly because foreign competition and warfare had ended the golden era of the guilds two centuries earlier.3 With markets shrinking, corporate masters began to exploit their hierarchical advantages. Hometown birth had become a near prerequisite for guild membership and related rights by the 1600s. Authorities forced widows to shut deceased husbands’ businesses, while towns like Göttingen and Leipzig barred female workers from weaving. Although male weavers benefited from this practice, most of these young journeymen found paths to their own shops blocked by oppressive guild controls. The resulting wave of journeymen’s strikes accelerated throughout the 1700s despite imperial attempts to restore order. One of the worst uprisings occurred in Aachen in 1786. Angry woolen workers stormed city hall and did not disband until troops from the neighboring Duchy of Jülich entered the gates. The empire appointed a commission headed by Dohm to rewrite the city’s constitution. Sobered on the subject of the guilds, he was in the process of recommending a dismantling of most of the guilds’ legal controlling rights when Campe and his friends visited him in 1789.

The Holy Roman Empire Before 1789

Guild abuses stood behind another significant challenge to the old ways. Frustrated by stifling corporate restrictions, renegade woolen and linen producers began as early as the 1500s to shift some of their operations outside city walls. They disbursed raw materials like wool to poor rural families for cheaply spun cloth, later collected by agents (factors) and returned to town for weaving and finishing. By the late 1700s this “putting out” system had spread throughout the Reich. In some regions, villages and small towns in the vicinity of guild-controlled cities grew into impressive centers of production. Rhenish Crefeld, Elberfeld, and Barmen grew into this new type of putting-out town, while west of Aachen, pre-industrial textile output multiplied in Burtscheid, Düren, Vaels, Monschau, and Verviers.4 The firm of Scheibler and Sons in Monschau had even begun to reassemble the spinning of high-quality woolens in town where “factors” (i.e. foremen) could monitor the work more closely under one “factory” roof. Aachen’s prosperity continued to decline, meanwhile, prompting an observant Campe to castigate “non-sensical” guild laws which “killed entrepreneurial initiative and undermined the welfare of the city.”5

The states of the Reich represented another threat to guild privileges. Prussia, for example, issued decrees transferring the political and regulatory power of these urban corporations to bureaucrats in Berlin. Other rulers established orphanages, workhouses, prisons, and lunatic asylums where inmates spun and wove goods sold by the state. The economic role of the state in eighteenth-century Germany extended further through monopoly charters, tax exemptions, and subsidies granted to non-guild businesses. Still other states established their own enterprises—about 6 percent of all large-scale manufacturing firms in German Europe during the late 1700s were fully state-owned, concentrating mainly on luxury items like porcelain, carpets, tapestries, hats, and lace, but also on foodstuffs like sugar, coffee, and chocolate. Although these mercantilist ventures provided much-needed income for princes usually strapped for funds, few were efficiently run, nor did they spawn modern industrialism. A more fertile seed, the above-mentioned putting-out system, constituted a remarkable 43 percent of German manufacturing production of all kinds and, as noted earlier, was gradually evolving toward a factory system.

Cottage industry was just one connection between urban well-being and the surrounding countryside. Cities sold most of their goods in rural areas where almost three-quarters of Germany’s population lived and worked. Furthermore, most food in cities came from outside city walls—and most raw materials, too. From the country came hops and barley for brewers, flax seeds for linen spinners, raw wool for woolen manufacturers, dye crops like moad and madder for dye works, leather for harnesses, pulleys, and the first machine belts, wood and stone for construction, and charcoal for iron makers. Germany’s manufacturing establishments represented a mere 2 percent of net investment in the late eighteenth century, while about 70 percent went into agriculture. Land was undoubtedly the most important means of production.

These circumstances help to explain the great influence wielded in state and society by landowners. Territorial princes usually possessed the largest tracts. The ruling Wittelsbachs owned about an eighth of the land in Bavaria, while the Hohenzollerns of Prussia held title to a third of Brandenburg and over half of East Prussia. The Catholic hierarchy, although representing a mere 1 or 2 percent of the population, also owned a significant amount of land—roughly half of all property in Bavaria, for example. In almost every secular and ecclesiastical state, furthermore, families of noble rank representing an even slighter 1 percent of the people possessed the lion’s share of real estate. This ensured them easy access to the ruler and a privileged status in government.

Thus Frederick the Great, king of Prussia from 1740 until 1786...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations and Maps

- Preface to Revised Edition

- Part I A Revolutionary Challenge, 1789–1815

- Part II The View From Vienna, 1815–1830

- Part III Opening Pandora’s Box, 1830–1848

- Part IV Answers to the German Question, 1848–1871

- Selected Bibliography

- Index