eBook - ePub

The Making of the Pentecostal Melodrama

Religion, Media and Gender in Kinshasa

Katrien Pype

This is a test

Share book

- 348 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Making of the Pentecostal Melodrama

Religion, Media and Gender in Kinshasa

Katrien Pype

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

How religion, gender, and urban sociality are expressed in and mediated via television drama in Kinshasa is the focus of this ethnographic study. Influenced by Nigerian films and intimately related to the emergence of a charismatic Christian scene, these teleserials integrate melodrama, conversion narratives, Christian songs, sermons, testimonies, and deliverance rituals to produce commentaries on what it means to be an inhabitant of Kinshasa.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is The Making of the Pentecostal Melodrama an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access The Making of the Pentecostal Melodrama by Katrien Pype in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Media Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

The First Episode

This book is about the production of Pentecostal1 television fiction in contemporary Kinshasa. Kinois people (inhabitants of Kinshasa) refer to the TV dramas as télédramatiques, théâtre populaire, and maboke.2 The title of the book can be read on two levels. On the one hand, it is an ethnography of the ways in which Pentecostal concepts and practices are presented to the urban audience in the space of television fiction and beyond (in TV talk shows discussing the teleserials, in church settings, in conversations among Christians). I will show how the Pentecostal message is negotiated in the religious and cultural spaces of Kinshasa. A major argument is that “the Pentecostal ideology” does not exist. Rather, Pentecostal concepts and ideas are constantly put into question and spur continuous reflection and debate. The Pentecostal imagination is all the time in the making. Second, this book offers at the same time an ethnography of the generation of TV fiction in Kinshasa. I trace the origins of plotlines and of fictional characters while also paying attention to the various social and spiritual interactions that occur during and beyond the filming, that is, in the interactions between the TV actors and their audiences, sponsors, spiritual counselors, and invisible agents such as demons and the Holy Spirit.

The material was gathered during seventeen months of fieldwork between 2003 and 2006.3 In the first month of fieldwork, when I was planning to study development-related theater in Kinshasa, the capital city of the Democratic Republic (DR) of the Congo, I attended a meeting of actors who had specialized in folkoric drama (ballet). The group, called Afrik’Art, felt disappointed by the directors of the Walloon-Brussels cultural center (CWB), which promotes local arts. Two years before my visit to their rehearsal space, the theater company had requested CWB staff to consider Afrik’Art for financial support. I was shown the official letter that had finally arrived after a year of waiting, in which a CWB official promised to attend one of their rehearsals. Since the arrival of the letter, the Afrik’Art actors had been anticipating the CWB visit at every single rehearsal session. Much to their disappointment, the official never showed up, and the group became aware that they needed to consider other routes if they wished to gain money and eventually make a living out of acting. My first visit was at an emergency meeting the group’s leader had organized to discuss the future direction of Afrik’Art. At one point, one of the actors suggested doing TV drama. Nearly every month, new TV stations were being set up, so the actor assumed they would not have any difficulty finding a TV patron who would give them a time slot and provide them with the material to film.

The idea was taken seriously by the others—and by the troupe’s leader, who apparently had considered this option as well and did not have to weigh the idea, since there were no other real alternatives. Very quickly he began to issue orders. One actor was to prepare a letter to the heads of the local television channels. This was not such a difficult task, since all of the twenty-six television stations4 on the air at that time broadcast local television drama (and continue to do so). Someone else had to approach shopkeepers and businesspeople who might have an economic interest in cooperation with the group. Much to my surprise at the time, another troupe member was told to ask the pastors in the neighborhood for spiritual guidance. If a pastor demanded that the troupe be part of the church as well, the leader added, they would not refuse. When summarizing this conversation in my notebook, I added an exclamation mark next to this third order. Little did I know then that I would be sucked into the world of born-again Christians and that pastors would become key informants.

Before I traveled to Kinshasa, development-related theater produced in a society concerned with social and political renewal seemed an original and highly relevant entry into the study of Kinois society, which at the time was coming to terms with the legacy of Mobutu’s failed political program and trying to find the right track to a prosperous future. In the initial months of fieldwork, I spent much time following theatrical troupes that produced plays on issues such as citizenship, domestic violence, and HIV transmission. Yet, I noticed, the Kinois themselves were far more fascinated by locally produced TV drama than by NGO-sponsored theater. I suddenly found the teleserials much more relevant than stage plays that people attended only if they were paid. Because of the strong interference of Pentecostal pastors in the promotion and design of local TV drama, this change of research topic meant that religion would become a major research matter, and I could not ignore the social value of the ubiquitous fictionalized visualizations of witchcraft and conversion to Pentecostal Christianity, which are the two main motors of the story lines in Kinshasa’s teleserials.

In Kinshasa, a city where ratings are unavailable to prove which are the most viewed shows and the most popular acting groups, it is commonly assumed that the acting companies Muyombe Gauche, Cinarc, the Evangelists, and Esobe produce the “best” serials and draw the most viewers. The ethnography draws on field research with various TV drama groups. Leaving aside the troupes Sans Soucis and Muyombe Gauche, each of which I worked with for a week, the bulk of my material derives from participant-observation with the company Cinarc, whose telenarratives are broadcast on privately owned channels (Tropicana TV: 2001–2005, RTG@: 2005–). TropicanaTV, the channel on which Cinarc’s serials were shown at the beginning of my fieldwork, is led by two journalists. In 2005, conflicts with the patron of TropicanaTV led Cinarc’s founder and leader Bienvenu Toukebana to search for another TV station to air their work. The politician Pius Mwabilu Mbayu Mukala offered the group the same broadcasting hours on his channel, RTG@, and an advantageous contract. Since the Cinarc serials’ inception, and even after moving to another television channel, the episodes have been aired on Thursday evenings (9–10 P.M.) and rerun on Friday afternoon (4–5 P.M.) and Sunday morning (9–10 A.M.).

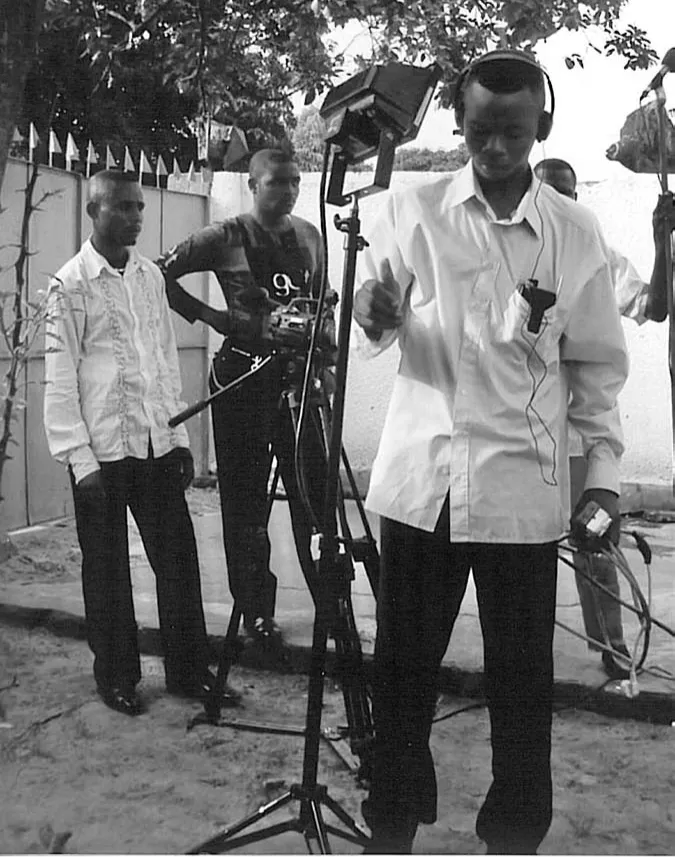

Cinarc was, at least during my fieldwork, by far the city’s most popular TV acting group (fig. 1.1). In 2005, two Cinarc actors were selected by all of Kinshasa’s television performers to receive awards for best actress and for best kizengi (fool, a stock character in Kinshasa’s serials; see Pype 2010). In 2006 and 2007, Cinarc won the annual Child of the Country Award (Mwana Mboka Trophy) for best TV acting group. This prize was awarded to them by audience vote via digital technology (mobile phone text and email). These local evaluations confirm that Cinarc is a significant player in the city’s media world. An analysis of Cinarc’s serials as well as its actors offers a relevant insight into Kinshasa’s popular culture.

Most remarkable for the Cinarc group is its explicit Christian proselytizing mission. Although most of Kinshasa’s troupes portray urban life from a Christian perspective, not all of these theater companies designate themselves “evangelizing groups.” The young Cinarc members imagine themselves as correctors of Kinshasa’s society. As I discuss in Chapter 7, the Cinarc artists intend to transform the city along Christian lines. Some of the actors even hold key positions in Pentecostal churches. It is exactly this explicit juncture between entertainment and religion that renders the Cinarc group the most popular in the city. Cinarc’s appeal reflects the hegemonic role of Pentecostal-charismatic Christianity in Kinshasa, and it accordingly guides the viewers’ media preferences.

Figure 1.1. Cinarc members filming (2006, © Katrien Pype)

Religion, Media, and Kinshasa’s Public Sphere

Like most of Kinshasa’s teleserials, the Cinarc serials primarily deal with domestic and social situations from a Pentecostal angle. One can understand this focus on the private and the “apolitical”5 as an escape from a harder, more “political” public sphere in a nation without a tradition of freedom of speech. During his long rule, President Mobutu6 attempted to control political discourse and did not hesitate to put artists in jail for criticizing his regime or mocking him or his collaborators. Laurent D. Kabila, Mobutu’s successor, also had a harsh take on media. Given such a legacy, we might gather that Kinshasa’s television actors hardly refer to political candidates or refrain from making overt statements about the state.7

Yet the religious nature of local TV serials, the existence of various television stations to which the Afrik’Art actors could write, and the fact that Cinarc’s proselytizing teleserials are broadcast on private, political TV stations resulted from several drastic changes that DR Congo’s society experienced during the 1990s. At that time, Mobutu’s power had considerably eroded, which was reflected in a more lenient political stance toward broadcasting technologies. In 1996, the president ordained freedom of press, thus enabling private patterns of media patronage. Joseph Kabila continued this openness of media.8 Immediately taking advantage of this opening to establish their own TV stations were all kinds of entrepreneurs, among them, in particular, commercial and political TV patrons. Crucially, since then, a significant part of Kinshasa’s local TV channels have been set up by Pentecostal-charismatic pastors, who have become increasingly influential in Kinshasa as elsewhere in urban sub-Saharan Africa. The public favor of this charismatic type of Christianity and the zeal of its evangelizers are so invasive that the Pentecostal message even spills over to non-confessional channels. State-run media and TV stations belonging to political and economic entrepreneurs also broadcast religious films and music and invite Pentecostal leaders onto talk shows as well. They do this because, as Pius Mwabilu Mbayu Mukala, a politician9 and also the director of the television channel RTG@, told me, “this is what the public begs for.”

The public role of Pentecostalism in post-Mobutu10 Kinshasa should be understood as functioning in a society where the state and its officials have difficulties to mobilize the citizens. Churches seem to be more successful in engaging Kinois for public work. This became most striking to me one Saturday morning when I witnessed crowds sweeping the main boulevards in a highly ritualized manner. Brandishing their brooms, chanting Christian songs, and praying out loud, these Christians removed all the rubbish from a particular street or roundabout while simultaneously chasing away the impure spirits identified by their leaders. This activity reminds one of the Salongo work that Mobutu inaugurated during his reign, when people (“citizens”) were obliged to clean their compounds, streets, and neighborhoods on Saturday afternoons. Fines were imposed on those who failed to help keep the city clean. Nowadays, rubbish is all around in the streets, and the state cannot discipline Kinois to keep the public space clean. It is a gripping example of the ways in which Christian leaders took over governmental tasks in the early 2000s.

The impact of religion on Kinshasa’s public sphere coincides with the new role played by religious media in many other societies (de Vries and Weber 2001; Meyer and Moors 2006). The crisis of the Congolese nation-state that started in the early 1990s created a vacuum, allowing Christian leaders to occupy public arenas like politics and stimulate entertainment, both in physical settings (ranging from church compounds to public spaces like roads and public transport) and mediated through electronic media. Pentecostal-charismatic churches have embraced television in particular as a useful instrument in their evangelizing mission. Although Kimbanguist, Protestant, and Catholic groups too have their own TV and radio stations, prophets and pastors who identify themselves as born-again Christians are much more successful in establishing media ministries. In the first instance, they set up electric churches to attract new converts. Broadcasting recorded prayer events and sermons in church is intended to stir religious enthusiasm among spectators and draw them to the church compound on Sunday mornings. Christian church leaders are eager to use television as an instrument in their proselytizing mission because most households in Kinshasa have a TV set. The participation of Pentecostal groups in Kinshasa’s mass media world is so pervasive that radio and television in Kinshasa have become important discussion forums as well as visual arenas of the religious imagination and the construction of an imagined Christian community (Anderson 1991).

Pentecostal churches are characterized by youthful enthusiasm and appeal, personally charismatic leaders, an explicit location in the modern sectors of life, and an overwhelming use of modern means of communication such as video, radio, and magazines (Van Dijk 2000: 11). They represent an utterly modern, cosmopolitan, transnational, and economically oriented type of Christianity (Coleman 2000; Van Dijk 2000; Corten and Marshall-Fratani 2001; Ellis and Ter Haar 2004; Gifford 1998; 2004; Meyer 2004a; Maxwell 2005; de Witte 2008; Marshall 2009). Pentecostal-charismatic pastors are often called “religious entrepreneurs,” thus hinting at participation in the local market and their fixation on business. In Kinshasa, and also in Ghana, as Gifford (2004: 33) documents, because of the mainline churches’ monopoly of the fields of education and development, Pentecostal churches draw most of their resources from their involvement in local media. Inspired by American televangelists, African Pentecostal-charismatic leaders videotape their services; publish and sell Christian pamphlets, DVDs, books, and other recordings; and establish their own radio and TV stations. Their commercialization and mediatization co-construct this new type of Christianity.11 As Gifford (2004: 33) notes for Ghanaian charismatic Christianity, “these media presentations are molding what counts as Christianity.”

Although Kinshasa’s religious field thrives on other economic, political, social, and cultural dynamics than what we encounter in west Africa, the Pentecostal-charismatic world and the media network overlap to a great extent in both locations. Much airtime is devoted to Christian talk shows; most services in churches are filmed. This footage then appears on the church’s television channel, or is simply sold within the congregation, or travels along transnational networks to the Congolese diaspora, where it structures their religious practices. On channels owned by Pentecostal pastors, and also in TV programs on non-confessional channels, narratives of witchcraft and occult events are presented, and pastors perform miracles and deliver people from satanic powers in the TV studio and via the screen. Further, Kinshasa’s teleserials are not imaginable without recurrent references to biblical figures, or even without mentioning pastors’ names and the programs of church services.

Many researchers are turning to the social, religious, and economic worlds of these new churches. Anthropologists are now also studying the interface of media and Pentecostal-charismatic Christianity. This has led to fascinating ethnographies that document how sub-Saharan African pastors use visual and aural media (Hackett 1998; de Witte 2008; Kirsch 2008; Meyer 2003a; 2003b; 2004b; 2009b). With this book, I aim to contribute to this growing literature on Pentecostal Christianity in Africa.12

In Kinshasa, Pentecostal churches have moved into the domain of television fiction also because the leisure segment is nowadays to a high degree free from state control and intervention. This contrasts with the Mobutu era, in which the services of the General Secretariat for Mobilization and Propaganda (MOPAPA, a part of the Ministry of Information) established national troupes that produced a theater of political cheerleading (Botombele 1975; Conteh-Morgan 2004). Political slogans, marching band music, and carefully choreographed performances not merely entertained the Zairians (as the Congolese were named then) and their visitors; they also produced intense emotional identification with the nationalist program (Conteh-Morgan 2004: 112; Kerr 1995: 205). Congolese television serials too originated from Mobutu’s propaganda. The first broadcast plays were commissioned by the head of state in order to mobilize Zairians to work for national development. Zaire’s first teleserial was called Salongo, meaning “work” (see Pype 2009b). The Groupe Salongo still exists today, though it now produces Christian teledramas.

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, under Joseph Kabila’s rule, however, the Con...