![]()

Chapter 1

ARBORESCENT CULTURE

WRITING AND NOT WRITING RACEHORSE PEDIGREES

Rebecca Cassidy

When Rivers popularized the genealogical model in the early days of the twentieth century, he created the possibility of comprehensive knowledge of society, and of each particular society. The model is apparently exhaustive (everyone has a mother and a father) and value neutral (the placement of men to the left of women and of the younger generations beneath the elder is merely conventional (Rivers 1900: plates II and III). As such, it is potentially liberating, universal, and in the context of the development of a structural-functionalist anthropology in opposition to the iniquity of social evolutionism, no doubt a ‘good thing’. However, the genealogical model contains a set of implications that militate against its use as a way of knowing and suggest that it is best thought of as a way of making knowledge of a particular kind. Apparently universal, inclusive and egalitarian, the genealogical model enshrines the modernist idea of progress.

The genealogical model is a theory of attribution. It fixes the direction of time by granting special status to temporal anteriority. It reduces individuals and events to the playing out of the inevitable properties of people and of objects. It presents the contingent as necessary, and in doing so provides evidence supporting the most conservative of interpretations of the present. Much of its utility depends on an ability to separate the model from society, to allocate it a place within ‘nature’, and this separation entails violence done to data that may suggest contradictory interpretations. This separation also suggests that the model exists in a historical vacuum, and that it has no relationship to the models that preceded it and to some degree made it thinkable, such as family trees, trees of life, and pedigrees. In this way the genealogical model denies aspects of its own ancestry.

In this chapter I want to explore some of the implications of pedigree thinking that, it has been argued, were part of the social repertoire on which the genealogical method drew (Bouquet 1993). More importantly, this chapter is an argument for suspicion of any kind of genealogy constructed without consideration of the particular way of knowing it might produce. As I will show through a discussion of nineteenth-century Bedouin and English thoroughbred horse breeding practices, merely producing a written pedigree transforms the manner in which knowledge about people (and horses) is envisaged. The recent creation of a cloned horse, the first in the world, has also provided a pertinent thought experiment for the current producers of the thoroughbred racehorse: what happens when pedigree stands still? What principles embodied by the pedigree (and by the genealogical model) are violated when descent is displaced by replication?

Context

Races between horses (or more accurately, between people mounted on horses) take many forms all over the world, from the pony races of Galloway and Iceland to the Percheron plough pulling of Japan. This chapter is only concerned with horse racing that adheres to internationally recognized rules and takes place exclusively between selectively bred thoroughbred racehorses, defined as such by their presence in the General Stud Book (GSB), first published in 1791. Thoroughbred racing takes place all over the world and is based on a highly specialized domestic animal and a template (of rules, conditions, etiquette) that originated in Europe, and specifically in Britain and Ireland.1 It consists of three interrelated activities: the production of thoroughbred horses (the bloodstock industry), the staging of racing, and wagering or gambling. Very simply, demand for thoroughbred racehorses is stimulated by prize money, prize money is levied from betting turnover, and maximal turnover demands racing that is perceived as competitive and fair.

Policing the boundaries of the breed has become increasingly important during the last century as competitions between thoroughbreds have come to dominate all other kinds of racing, including trotting, harness racing, pony racing and Arab racing. To a large degree, today racing is thoroughbred racing. A vast international sport and industry has been created based on this dominance. Pedigree is the mechanism that links the fortunes of the bloodstock industry with those of the massive wagering industries (currently estimated as constituting a £1 trillion market worldwide [Davis 2001]), because it limits the supply of horses capable of providing what has come to be regarded as the authentic racing product.

The Roman Emperor Septimus Severus is said to have staged races between imported Arabian horses at York in 210 (Lyle 1945: 1). Having been wholeheartedly appropriated by Tudor and Stuart kings and queens, racing was subsequently exported by the British Empire to several of its colonies, most notably the U.S., Canada, Hong Kong, Australia and New Zealand. Recognizably British racing is still popular in India and in several former colonies in Africa, including Mauritius, where the Champ de Mars, one of the oldest courses in the world, has held races since 1810. At the present time the fastest-growing racing jurisdictions are those of Japan, Singapore, South Korea and Hong Kong.2

My fieldwork takes place amongst the present-day custodians of the thoroughbred. Entry into this world depended not just on my ability to move safely amongst live racehorses, but also to navigate my way through the links created by their ancestors, both human and equine, dead and alive. To a degree that can seem entirely baffling to the outsider, pedigrees and genealogies establish ‘who's who’ in the bloodstock industry. Amongst horses, breeding sells, and pedigrees are claims that must therefore be regulated (the GSB and the paraphernalia associated with breeding racehorses have enshrined this opportunity for wealth creation). The keepers of national stud books maintain strictly enforced regulations concerning entry, overseen by the International Stud Book Committee and supported by increasingly sophisticated identification systems.3 Amongst people, as this chapter will show, breeding suggests entitlement. The grammar of pedigree is particularly compelling to a group of people for whom daily life consists of the acting out of the principle that ‘like begets like’.

Images

The pedigree is the central organizing image of the bloodstock industry. To the extent that the value of a horse is more easily predicted by reading its pedigree than it is by looking at it, the ‘dry facts’ of breeding are more important than the ‘flesh and blood’ to which they relate. When thoroughbreds are sold at public auction as one-year-olds (referred to as ‘yearlings’), they are assessed first by their pedigrees. A horse that is of reasonable conformation (muscular and especially skeletal form) will be expected to reach a certain price at auction. A yearling of average conformation with different breeding will be expected to reach a different price. The yearlings are therefore grouped together primarily on the basis of pedigree and only secondarily on the basis of appearance – despite the fact that pedigree is far from foolproof in predicting an individual horse's ability.4

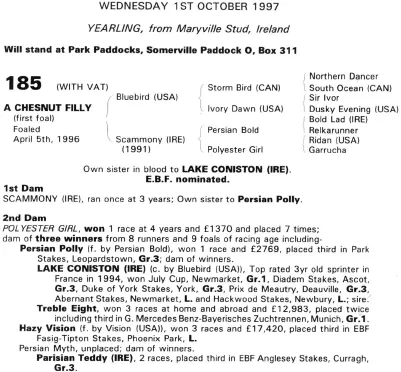

Thoroughbred pedigrees, in their standard format as they appear in sales catalogues, are read from left to right (see Figure 1.1). The individual whose breeding is recorded is alone on the left. The name of her sire, in this case Bluebird (USA), is recorded to the right and above. The name of her dam, Scammony (IRE), is recorded to the right and below them both.5 This format is repeated for each ancestor over four generations, so that the final line of the pedigree records eight individuals, sires above dams. In addition, information detailing the relatives (male and female) of her female relatives is provided in a list below the pedigree itself. This roster begins with the dam and continues with her offspring, and the offspring of her offspring. It then lists the second dam, her offspring and the offspring of her offspring. This process continues until the page is full. The information provided at this point is often highly selective. Breeders search for successful racehorses that can be linked with their mare, often described as a search for ‘black type’ (a reference to the fact that success in the most important international ‘Group’ or ‘Graded’ races are recorded in black type).6 This page is littered with black type, showing that the relatives and progeny of this mare have already been successful and suggesting therefore that this yearling will be similarly talented.7

FIGURE 1.1: Catalogue page.

The pedigree has two aspects, the upper male line, recording sires and sires of sires, which constitutes the strength of the pedigree, and the bottom line, which records the dam and dams of dams. During my fieldwork, the sire line was said to represent the strength against the weakness of the dam line. The purpose of the additional information offered regarding the mare was to reassure potential buyers of her relative lack of weakness. At auction, the sire will usually be far more influential in determining the price of the yearling than the dam, who was described to me by one of my informants as nothing more than ‘a mobile incubator’. This idea is clearly expressed in the shorthand for yearling pedigrees, which in this case would be ‘Yearling, Bluebird (Persian Bold)’.8

Pedigrees are not just employed to represent the quality of individual horses, but also serve as a kind of motif running through all of the stories that the racing industry tells itself (and others) about itself. Historians of racing society produce stories that combine humans and horses in mutually supportive genealogies. Selective breeding uses a patriarchal and aristocratic theory of heredity to determine mating decisions, just as the producers of racehorses use this theory to explain the outcome of unions between humans. This is history of the kind criticized by Nisbet, in which ‘events have events, as women have babies’ (1970: 354).9 Particular dynasties are linked to the fortunes of particular equine lines, and this conflation of human and animal is used to express the implicit logic of all pedigrees, that ‘blood will tell’. In the language of the genealogical historian, the explanation for the present lies in the properties of the past. However, amongst thoroughbred breeders an extra incentive to adhere to the idea of pedigree is provided by the idea of improvement, because it is here that gains in status can be made. The pedigrees of successful horses do not just offer ‘proof’ of the efficiency of selective breeding; they also credit the person who arranged that mating with the ability to improve nature.

In a recent book about Ascot racecourse, I was struck by the juxtaposition of four pedigree-like diagrams, recording a series of human and equine relationships (Onslow 1990). Ascot is one of the premier racecourses in England, and the Royal Meeting over four days in June is perhaps the most famous race meet in the world. Once the central event in the social calendar of the Edwardian aristocracy, it is still important to the well-heeled. Each day of the meet is opened by a royal procession: the queen and her guests are transported by open horse-drawn carriage down the centre of the course to wave at the racegoers as the band of the Blues and Royals plays the national anthem in the stands. The meet is a British institution, covered by a team from the BBC including the royal correspondent and a squadron of fashion experts breathlessly describing the importance of a good hat and the difficulties of obtaining made-to-measure gloves.

The endless books written about Ascot are mostly the responsibility of the tame racing press. Typically, an author will celebrate the racecourses of the world before going on to say that Ascot is by far the best: ‘Elaborate splendour, often allied with elegance, and even sheer beauty, is the hallmark of (all racecourses), but none has the indefinable quality that the presence of the sovereign, pageantry, fashion, and racing of the highest quality combine to give to Royal Ascot’ (Onslow 1990: 206).

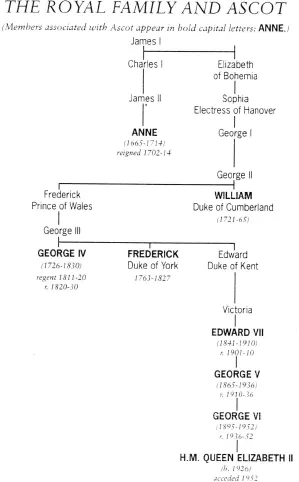

In this case, the author is determined to stress the inevitability, the ‘rightness’, of this combination of human and animal excellence. On four pages, Onslow depicts the royal founders and supporters of Ascot, the most successful trainers at Ascot, and the pedigrees of winners of races at Ascot. The blurring of distinctions between humans and animals is particularly suggestive; the same hereditary principles are operating in each case.

Queen Anne founded Ascot in 1711 (see Figure 1.2). Whereas her great-grandfather James I and uncle Charles II had been devoted to the racing and hunting opportunities of Newmarket Heath, Anne planned to develop Ascot so that she might watch racing whilst the court was based nearby in Windsor. Indeed, Charles II does not even appear on the diagram.

FIGURE 1.2: Royal Family and Ascot.

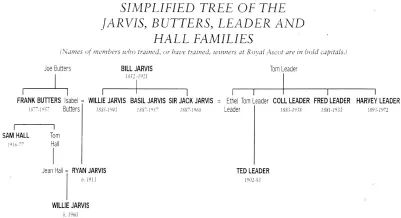

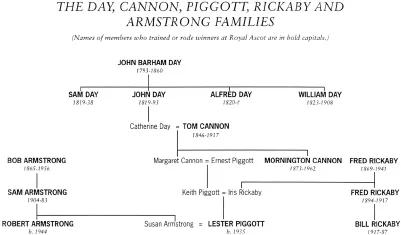

These two trees can actually be linked, and the dynasty as a whole still has a close involvement with racing in Newmarket. During fieldwork, one of the first racehorse trainers I met (in the pub that served as ‘local’ to both of us) was a member of this family. As soon as he discovered that I was an anthropologist, he started telling me about his relatives and, to my surprise and consternation, began drawing a family tree on a paper napkin left over from our lunch (see Figures 1.3 and 1.4). All of my own reservations about the genealogical method were swept aside in his confident enthusiasm that this was ‘just the stuff I needed’. During the course of my fieldwork, spent meeting a highly selective group of his relatives, I recorded approximately five hundred individuals in nine generations.

FIGURE 1.3: Simplified Tree of the Jarvis, Butters, Leader and Hall Families.

Just as Onslow's trees omit individuals that do not serve to connect those associated with Ascot to each other, I found that I was recording some rather strange relationships. In particular, I found that people were reproducing asexually. At first I put this down to my lack of focus – I was happy to listen to stories about relatives, but I was both lazy about the actual business of representing each person symbolically, and resistant in principle to such a practice. What did such a practice conceal? Was this method of recording data making alternative interpretations impossible? When the problem of missing ancestors persisted, I mentioned it to an informant. I was told that of course people who were not associated with racing were omitted, so long as they didn't provide any links to other racing families. I tried to persuade my informants not to do this, and we argued the point. The compromise position that emerged was that we put a diagonal line through these human dead ends. When children were subsequently produced by nonracing relatives, this had the bizarre effect of recording reproduction that had apparently taken place from beyond the grave.

FIGURE 1.4: The Day, Cannon, Piggott, Rickaby and Armstrong Families.

In this case, the maintenance of ideas that pedigrees appear to express is more important than the tracing of biogenetic relationships. Pedigree is more than the tracing of blood ties; it is also the concentration of the social imagination on links that do in fact support the implicit suggestions of imagining relatedness in this way, as is clearest in the final case, the Royal Ascot winners in the male line from Stockwell (see Figure 1.5).

What is interesting about this particular pedigree is that it is no longer bilateral, as Franklin has observed of Dolly the sheep's genealogy (1997). Whilst Dolly's genealogy eliminates the ‘noise’ of sexual reproduction, this pedigree or line shuts out the noise of mares and (other) losers. Causation is stripped down: Stockwell produced Doncaster, who produced Bend Or, who produced Bona Vista, etc., right up to Northern Dancer. This is the symbolic expression of patriarchy.

Origins

Arab horses have been exchanged as gifts since Sheikh Haroun Al Rashid sent five to Charlemagne in 800 (Boucaut 1905: 121). However, the exchange of horses between East and West that eventually produced the thoroughbred in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries began in earnest with the import of Arabs by Emperor Septimus Severus in the second century.10 Septimus Severus was born in Africa and had fought his way across the Middle East, the ‘cradle’ of the Arab horse, before finding himself in Weatherby, in Yorkshire, where he conducted what are generally thought to be the first races in Britain (Lyle 1945: 1). Records from the time of King John suggest that the transportation and exchange of horses in order to improve the quality ...