- 258 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Located within the forgotten half of Europe, historically trapped between Germany and Russia, Estonia has been profoundly shaped by the violent conflicts and shifting political fortunes of the last century. This innovative study traces the tangled interaction of Estonian historical memory and national identity in a sweeping analysis extending from the Great War to the present day. At its heart is the enduring anguish of World War Two and the subsequent half-century of Soviet rule. Shadowlands tells this story by foregrounding the experiences of the country's intellectuals, who were instrumental in sustaining Estonian historical memory, but who until fairly recently could not openly grapple with their nation's complex, difficult past.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Shadowlands by Meike Wulf in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 20th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

UNDERSTANDING COLLECTIVE MEMORY AND NATIONAL IDENTITY

Remembering in order to belong.

– Jan Assmann, ‘Erinnern, um dazu zugehören’1

When a big power wants to deprive a small country of its national consciousness it uses the method of organized forgetting …

A nation which loses awareness of its past gradually loses its self.

– Milan Kundera (in interview about The Book of Laughter and Forgetting)2

A nation is a soul, a spiritual principle.

Two things, actually, constitute this soul, this spiritual principle.

One is in the past, the other is in the present.

One is the possession in common of a rich legacy of remembrances; the other is the actual consent, the desire to live together, the will to constitute to value the heritage which all hold in common.

– Ernest Renan, ‘Qu’est-ce qu’une nation?’3

Estonian history in the twentieth century inevitably poses questions about the effects of war, military occupation, authoritarian rule and socio-political rupture on collective memories and identities. In this chapter I will discuss these issues on a conceptual level. Which memories can be preserved, which will be transformed and which are permanently lost? How far is collective memory important for the continuity of a group, such as a nation? Understanding the social dynamic of continuity and change in modern societies has been the main focus of sociologists, but it is also a key concern in the field of memory studies. This opening chapter intends to provide a good theoretical understanding of the interrelated concepts of collective memory and national identity, as well as history and generation, and to lead – as a sort of ‘toolkit’ – into the case study of identity formation in post-Soviet Estonia. The relation of collective memory to processes of national identity formation forms the logical axis of this chapter as well as the next. To be sure, memory and identity are highly elastic concepts that need to be clarified. Whereas this chapter sets up the concept of collective memory as a synthesis of the works of founding figures Maurice Halbwachs, Pierre Nora, Jan and Aleida Assmann, Jacques Le Goff and Jeff Olick, Chapter 2 will discuss Estonian collective identity formation between Teuton and Slav. I will add my own theoretical refinement to the discourses on memory studies and nations and nationalism in three ways: understanding national identity through collective memory and establishing the link between the two concepts; launching the concept of generational identity as an alternative to ethnically defined collective cultural identities; and rethinking collective memory for the East European context. In addition I shall tackle questions of the social and political functions of collective memory in modern society, and the mechanisms of its transmission.

Mechanisms of Collective Memory

The anthropologist Elizabeth Tonkin’s aphorism ‘memory makes us and we make memory’ captures well the intertwined mechanisms underlying the concept of memory and points to its socially constructed nature. To start with, memory is embodied individual memory because there is no living entity such as a ‘collective memory’, there are only collective memories.4 The first part of Tonkin’s quote – ‘memory makes us’ – hints at the social framework of memory, which both informs and restricts its group members’ thoughts and actions. Thus, group members perceive and interpret the past, present and future through these social frameworks, a process that Francis A. Yates referred to as seeing through the ‘eyes of memory’.5

However it was the French sociologist Maurice Halbwachs who in the 1920s first placed individual memory within the larger framework of society, claiming that individual memory requires the support of a collective for its existence, maintenance and reconstruction. He further argued that it is only through group membership that individuals acquire, localize and recall their memories. These socially prescribed cognitive frames are systems of conventions that, due to their partial and biased nature, impact on how and what the group remembers. Because of this the social framework of society is essential to processes of individual remembering, which is the main reason Halbwachs coined the term ‘social memory’. It is because social memory is inextricably connected to a specific social framework that it is limited in time and space. In other words, human life is finite and groups vanish. Another reason for labelling individual memory as social memory is that it is structured through language and based on communication. It is indeed language that forms the link between the collective and the individual enabling conversation and sharing, including even those group members who lacked the first-hand experience of certain events in the imagined reconstruction of the group’s collective memory. Here the mechanisms of transmission of memory can either be familial and unmediated or mediated through public institutions, such as schools and libraries. Recognizing that we participate in a range of different groups throughout our lifespan and that individual memory is an agglomerate of various group memories, Halbwachs introduced the term ‘collective memory’ in addition to social memory. He later also employed collective memory in the plural to emphasize the many different social memories coexisting in a society at any one time.6

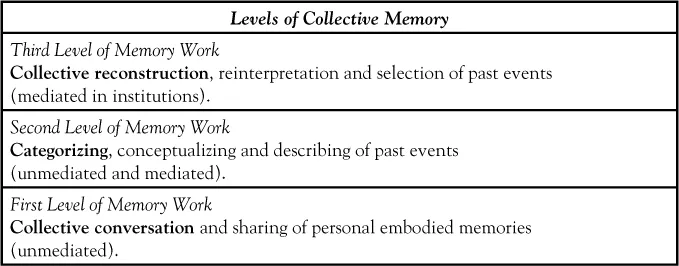

‘We make memory’, the second part of Tonkin’s quotation, stresses the constructed and constantly reprocessed nature of social memory. This means the past is not merely preserved but is continuously and selectively reconstructed in the light of present interests, needs and aspirations.7 To make more explicit the point that collective memory is a social process, Jay Winter prefers the term ‘remembrance’ instead of collective memory. This social process or activity of reconstructive ‘memory work’, to employ Freud’s term, takes place in the aforementioned social frameworks and comprises three levels: first, collective conversation; second, categorizing and conceptualizing past events; and third, more abstract processes of reconstruction and selection.8 As we move from the first level of collective memory work to the third, we are also moving from more unmediated forms of personal sharing of the past to mediated forms of institutionalized interpreting of the past. These multilevelled processes of collective memory are made visual in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Collective Memory: Three Levels of Memory Work

Continuity and Change in Collective Memory

To give a preliminary definition: collective memory constitutes a repository of shared cultural resources (such as language), which guarantees continuity of a group. Change lies in the continuous process of reconstruction, reinterpretation and selection of these cultural resources; in the how and what is remembered at any point in time. Halbwachs explained changes in the collective memory through an altered social framework, but it was Friedrich Nietzsche who pointed out that forgetting the past is as vital as remembering it for the endurance of a group. Forgetting, he argued, is the capacity of a people to accommodate change and to recreate and transform themselves in the light of present and future challenges.9 To understand continuity and change in collective memory, we need now to consider more carefully the different aggregate states of collective memory: it can manifest itself in more fluid and fluxionary forms or turn into forms which are more durable and lasting. Oral traditions, for example, can be classed as fluid, whereas archives and monuments constitute more crystallized forms of collective memory.10

Halbwachs’ way of accounting for continuity and change in collective memory was to distinguish between ‘historical’ and ‘autobiographical’ memory. Whereas the former is periodically re-enacted through commemorations, festivals and rituals, the latter refers to the personal memory of events. But this autobiographical memory will fade over time unless regularly reinforced through contact with other group members who have shared past experiences.11 It is important to note also that Halbwachs did not employ the term ‘cultural memory’: launching the dual concept of communicative and cultural memory to account for the dialectic interplay of continuity and change in collective memory can be credited to the Egyptologist Jan Assmann. Because communicative memory depends on language, it is ephemeral; but this also gives the group flexibility to adapt to the changing requirements of modernity. Communicative memory encompasses all experiences that are personally communicated over a time span of up to four generations. On the other hand it is through its long-lasting, institutionally manifested and thus externalized forms of memory that cultural memory ensures continuity. Cultural memory is recorded, codified and transmitted through literary tradition, cultural artefacts and forms of institutionalized communication, and is therefore trans-generational and long lasting, externalized from the individual embodied memory. We can therefore conclude that language plays a pivotal role for communicative memory, while tradition forms the backbone of cultural memory.12

The shift from oral traditions to script cultures profoundly transformed collective memory. It was particularly the innovations of print technology, a central bureaucracy and the ideology of nationalism as features of European modernity that had deep effects on the development of cultural memory. For instance, the French Revolution, with its new calendars and festivals, all in the service of its own remembrance, can be seen as a benchmark in the secularization and multiplication of public commemorations.13 Similarly in the late nineteenth century it was the creation of national archives, public record offices and historical research institutes after the national unifications of Italy and Germany that formed notable manifestations of cultural memory. After the First World War, monuments to the dead – such as the tomb of the Unknown Soldier – but also photography and film, further revolutionized cultural memory.14 With these developments in mind, the literary scholar Aleida Assmann has argued for a further differentiation of cultural memory into an active ‘functional memory’ and a more latent ‘stored memory’, two terms that can be understood as foreground and background of cultural memory. In other words, while the functional memory contains only a selection of the resources and traditions of a society’s cultural memory depending on its present needs and interests, the stored memory contains the larger pool of knowledge independent of political currents and short-term developments.15

Time in Space: Sites of Memory

We have seen that collective memory is anchored and unfolds in a social framework, but groups locate and solidify their collective memory also in a spatial framework, helping them to retrieve memories through landmarks.16 Anthony Smith holds that the homeland, as an ancestral land of saints and sages and historic battles, constitutes a repository of historic memories aiding national reassertion in times of foreign domination.17 Certainly in Estonia, a country that has been under foreign rule for most of its modern existence, the landscape was linked to the history of the community and to collective identity. In Chapter 5 I shall examine various landmarks of cultural memory in contemporary Estonia, such as monuments and memorial sites connected to the wars.

Although Halbwachs began to develop ideas on topographical memories in The Legendary Topography of the Gospels...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- CONTENTS

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Shadowlands

- Chapter 1 Understanding Collective Memory and National Identity

- Chapter 2 Between Teuton and Slav

- Chapter 3 Historians as ‘Carriers of Meaning’

- Chapter 4 Voicing Post-Soviet Histories

- Chapter 5 A Winner’s Tale: The Clash of Private and Public Memories in Post-Soviet Estonia

- Conclusion: Framing Past and Future

- Appendices

- Bibliography

- Index