![]()

Chapter 1

ON ETHNOGRAPHIC NOSTALGIA

Exoticizing and De-exoticizing the Emberá, for Example

Dimitrios Theodossopoulos

Ethnography is an inherently nostalgic exercise because it emulates a previous experience, a memory of fieldwork, articulated in dialogue with a previous ethnographic record or the narratives of others. In recent work (Theodossopoulos 2016), I have used the term ‘ethnographic nostalgia’ to refer to the inclination of ethnographers—and in general, authors who try to record cultural practices—to pursue nostalgic connections between a present social reality and what other people (previous authors or key informants) have said about a particular society before. Ethnographic nostalgia emerges from the comparison of the ethnographic object as encountered in the present with previous written or oral descriptions, for example, the ethnographic literature or local lore. According to this definition, most theories that attempt to uncover structural patterns—for example, most types of structuralism—flirt with the possibility of generating a certain nostalgic view. This is often predicated in the analytical attempt to identify an underlying structure by comparing an imperfect present with an increasingly idealized past.

When one’s thoughts and observations are committed to paper, it is very hard to follow up the rhythm of social transformation. By the time a description of social life has been articulated—published, formalized, accepted as representative—society has already changed in numerous unanticipated and as yet unaccounted for ways. It is to here that we can trace the roots of ethnographic nostalgia: the present ethnographic reality does not always fit, and often compare unfavorably, with the more perfect, well-articulated picture of the ethnographic record. The latter may be polished, already idealized, selective, often legitimized as a standard of authenticity. And this is why so many ethnographers relate to the present social reality in ‘allochronic’ terms, placing the peoples they study in another, distant, and safer time (see Fabian 1983), which generates nostalgia and a desire to salvage “ethnography’s disappearing object” (Clifford 1986: 112; see also Berliner 2015).

‘Ethnographic nostalgia’ has an affinity with two other types of nostalgia identified by Renato Rosaldo (1989, 1993) and Michael Herzfeld ([1997] 2005). Rosaldo’s ‘imperialist nostalgia’ focuses on the paradoxical lament of the colonizer for what colonization has already destroyed (1989). The Western observer longs for what the Western civilizing mission has radically transformed, romanticizing Otherness—which is seen as lost and therefore unthreatening—seeking absolution in the presumed innocence of such a nostalgic longing, as if domination could be erased. Herzfeld’s ‘structural nostalgia’ uncovers a nostalgia that emerges from a comparison with the past, an idealized and irrevocable age of reciprocal sociality (2005). It is to be found both in official and local discourses—not only colonial narratives—when idealized narratives about the perfection of relationships in a previous, more sociable and authentic era are evoked to frame commentary for a less perfect present. The longing for former, better times, representative of ‘structural nostalgia’, may inform a desire to salvage what is perceived to be disappearing, which is so representative of ‘imperialist nostalgia’.

Imperialist and structural nostalgia together substantiate ‘ethnographic nostalgia’. The Western ethnographer—or the auto-ethnographer who adopts a Western epistemology—longs for what Westernization has transformed, seeking connections with an authentic representativeness found in narratives about society in the past—for example, the previous ethnographic record. The ethnographic record is imagined as a lost social world, idealized and purified in its written articulation, and therefore works as a standard of authentication, framing nostalgia and exoticizing the present in comparison with an imagined, well-structured, and articulated past. The ethnographer—or culture writer, more generally—may identify this artificially structured and, ultimately, imagined past in old cultural patterns that emerge spontaneously in the present; which often stimulate a sense of nostalgic recognition.

It is in this respect that the ethnographic process engenders a certain degree of nostalgic exoticization. My aim here is not to merely identify this danger but also to provide a more constructive message. Ethnographic nostalgia, despite its patronizing and idealizing proclivity, can generate the conditions of its own demise. It may lead—through reflexive self-questioning—to the recognition of intentionality in social life, leading to a confrontation with the essentialisms of the exoticizing nostalgic view. Nostalgia may also “engender its own ironies” (Battaglia 1995: 78), play a role in social life as a transformative force (Angé and Berliner 2015b), and be used by local actors as a discursive tool to subvert or highlight contradictions (see Herzfeld 2005). As such, vernacular—locally expressed, non-authorial—nostalgia can stimulate the revitalization or readaptation of older cultural themes in the present, produce new arguments about cultural representation, and breed creativity in unpredictable ways (Bruner 1993; Hallam and Ingold 2007)—a transformation of what is seen as tradition which may be conceived to be ‘inventiveness’ (Sahlins 1999: 399).

But let us return to the nostalgia experienced by authors who write about society. To the degree that their—‘ethnographic’—nostalgia inspires the pursuit of what has been previously described or said about the past in the present, it paves the way for confronting complexity and the possibility that the present is not exactly like the past. Such contradictions may complicate previous authenticating ethnographic accounts or expose their incompleteness. Or, on the contrary, they may attract attention to reemerging cultural patterns that may unite the past with the present, in recognition that what was recorded before—and structured as the object of ethnographic nostalgia—is now part of a new configuration of knowledge. Bruce Kapferer has recently refigured the anthropological use of the exotic by directing attention to the moment of exotic recognition: the search for new possibilities “at the edge of or beyond knowledge,” the exotic as a “challenge to understanding” (2013: 818). Such moments of exotic recognition may challenge and undermine one’s attachment to a previous nostalgic view, destabilize the established pathways of authentication, and engender a de-exoticizing, de-essentializing awareness of complexity.

In this chapter I will highlight some of the obstacles that academic analysts confront when they attempt to contain their proclivity to exoticize, which is inherent in the practice of writing about societies. To avoid offending any particular colleague, or the broader academic community, I will focus my analysis on my own exoticizing tendencies during my struggle to understand the cultural practices of the Emberá, an Amerindian indigenous group. I believe the lessons I learned from this exercise will interest a broader academic audience, primarily academics engaged in ethnographic research, but also, indirectly, indigenous leaders and writers who produce narratives that inform cultural representation. Many authors who write about cultural practices—of their own people or others—are tempted to exoticize, to a greater or lesser degree, in a nostalgic manner. As with ethnocentrism, the distorting lenses of nostalgia and exoticization represent a constant challenge: the more biases we uncover, the more we are bound to discover.

Nostalgia about Emberá Clothes

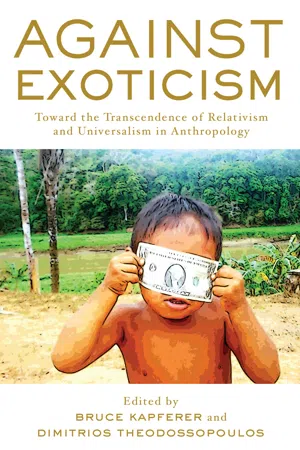

My first gaze of the Emberá, dressed in their traditional attire, elicited a type of nostalgia very common among audiences of Westerners who visit indigenous groups (cf. Bruner 2005; Salazar 2010): a desire to encounter indigeneity uncontaminated by modernity, representative of a hidden, isolated, and authentic world. This is a naïve, romanticizing, but crypto-colonial nostalgia, ‘imperialist’ in Rosaldo’s (1989) words. When I saw the Emberá welcoming me decorated in full traditional garb, wearing loincloths, colorful paruma skirts, beaded necklaces, and body paint designs, my mind stopped for a fleeting moment, as if I wanted to embrace and hold onto this image of quintessential, uncomplicated indigeneity, as if it was possible to stop the clock, reverse time, and experience what I had read about the Emberá in books.

FIGURE 1.1 A first view of the Emberá of Parara Puru

Sketch © Dimitrios Theodossopoulos

The first Emberá I met were the residents of Parara Puru, one of a small number of Emberá communities close to the Panama Canal that receive regular visits from Western tourists. Parara is in all respects an organic, inhabited community—not a tourist enclave (Edensor 1998)—home to around 20 Emberá families, organized along the lines of the available system of political representation in Panama.1 Its inhabitants nowadays work full time in indigenous tourism. Every other day—for the greater part of the year—they welcome and put on performances for tourists, and, after the tourists depart, they carry on with the usual chores of their everyday life. As a result, their compelling ‘traditional’ attire, I soon realized, was a temporary dress, a costume to wear during part of the day, before putting on, as all other Emberá in Panama, their ‘modern’ (as they call them) clothes.

Many tourists who visit the community seem to be surprised at the extent to which Parara Puru and its inhabitants closely match Western expectations of the appearance of indigenous Amerindians (see Theodossopoulos 2011). The tourists often describe the ‘dignity’ conveyed by the Emberá, who present their culture without begging for money or hustling their visitors. However, a few tourists, after recovering from their first overwhelming surprise, question the authenticity of the community (see Theodossopoulos 2013a) or express some reservations: “Is this really a real community?” “It looks too good to be true.” “Are the Emberá dressed like this all the time?” “They look so much like real Indians!”

This suspicion of inauthenticity on the part of several Western visitors led me to return to Parara, after visiting many other ‘non-touristy’ Emberá communities in Eastern Panama. And I kept on returning, for the next decade, to conduct anthropological fieldwork and participate in the life of the community, an experience I have described in detail elsewhere (Theodossopoulos 2015, 2016). In the meantime, the issue of Emberá clothing kept on emerging and reemerging as a central theme, uniting different parts of my research. I have taken careful notes on what the Emberá describe as ‘traditional’ or ‘modern’ clothes, compared current practices with the ethnographic record, and provided my own neat and clearly outlined description of Emberá clothes (cf. Theodossopoulos 2012, 2016)—all of which have structured, and continue to inform, my ethnographic nostalgia.

But let me return to my first sight of the Emberá, since I now see that it played a trick on my exoticizing imagination. My nostalgia was more unforgivable than that of the tourists, considering I had already spent a good portion of my life teaching anthropology. Having persistently advocated the importance of resisting the temptation to see society in static terms, I myself was not prepared to surrender without a fight to my desire to see the Emberá in indigenous clothes. But the embarrassing realization was that such a nostalgic desire had indeed emerged. Was I the same person who had previously criticized the old-fashioned anthropologist, preoccupied with the ‘tribal’ peoples of faraway lands? In European anthropology, on which I had previously worked, this exoticizing perspective had been seriously questioned and destabilized (see Goddard et al. 1994; Just 2000). It was precisely because of my firm commitment to this critical perspective that I was so disappointed every time I caught myself longing for cultural difference untouched by modernity. This nostalgic feeling was in fact unredeemable in a double sense: unforgivable, despite the redeeming illusion conveyed by nostalgia (see Clifford 1986; Rosaldo 1989), but also inescapable—the more I tried to get rid of it, the more nostalgia I discovered within myself.

As soon as I realized it was impossible to kill my nostalgia once and for all, I decided to ignore it, focusing instead on the task at hand: documenting the subtle nuances of the Emberá clothing practices. This plan seemed to work at the outset, because the complexity I encountered worked as an antidote to nostalgia’s essentializing vision. For example, I was soon able to recognize that the dichotomy between the traditional Emberá attire and their modern dress codes was not as impermeable as I had first thought. In fact, there was significant scope for accommodating modern as well as indigenous elements in the dress of the Emberá, which produced original combinations. Take, for example, the women, who combine in their everyday life their paruma skirts, which are mass manufactured but conceived of as indigenous, with a variety of modern tops. This practice has resulted in a distinctive indigenous—Emberá-Wounaan2—dress code, used extensively both inside and outside Emberá and Wounaan communities. Similarly, to offer another example, traditional or nontraditional jagua body paint designs—the old and diverse indigenous practice of body painting (cf. Ulloa 1992)—are matched with modern clothes in a variety of unpredictable ways, by young Emberá and Wounaan men and women.

Having recognized that various mixed modern and indigenous elements were incorporated into contemporary Emberá dress codes, I was able to appreciate the fluidity of Emberá cultural practices: that there was no deep, unyielding distinction between ‘tradition’ and ‘modernity’, no dichotomies, painful rifts, or a sense of irrevocable loss (the type of discontinuity so sharply underlined by imperialist nostalgia). Several Emberá clothing fashions in the past and present have emerged as transformations of previous transformations (Gow 2001) that have developed organically as the Emberá combine what they see as old (traditional and/or indigenous) with what they see as new (modern and/or exogenous). It is this fine balancing act that engenders the various Emberá ‘micromodernities’ that become in time “a synonym for current custom or personal performance” (Knauft 2002: 20). If we accept that neither modernization nor change are “incompatible with being indigenous” (Conklin 2007: 25), we are much more likely to agree with the Emberá when they insist that they remain distinctively Emberá in spite of the clothes they wear—modern, traditional, or mixed.

Such a fluid and processual view of modernity—that focuses on what can be seen from a local point of view as alternatively modern (Knauft 2002)—can be seen as another antidote for nostalgia and the vision of the vanishing cultures it perpetuates. Indigenous groups all over the world may choose to strategically resort to the visual exoticism (Conklin 1997) of their ‘traditional’ attire to communicate with wider audiences of potential sympathizers (see Bruner 2005; Conklin 1997, 2007; Ewart 2007; Faris 2007; Gow 2007; Knauft 2007; O’Hanlon 2007; Santos-Granero 2009; Turner and Fajans-Turner 2006; Veber 1992, 1996). In this respect, the Emberá of Parara Puru and other Emberá communities that entertain tourists are not exceptional. However, their use of the full traditional attire during cultural presentations should not be seen as a reassertion of what has been lost, as the nostalgic perspective implies. Instead of contradicting modernity, the full Emberá attire as used in the present is another expression of modernity’s many faces: a new representational strategy (Bruner 2005).

The tourists who suspected inauthenticity on the part of the Emberá of Parara Puru were correct in assuming that the Emberá wear full traditional attire only for cultural presentations. It must be noted, however, that even in the time of their grandparents—which the Emberá attire, in its contemporary use as a costume, represents—the Emberá only wore the full complement of their adornments for special occasions and celebrations, including visits from Western outsiders (see Howe 1998; Marsh 1934; Taussig 1993; Verrill 1921). When the tourists depart, the Emberá of Parara Puru carefully stow away their adornments—various types of necklaces, belts, and bracelets3—to carry on with their daily chores, very much as their ancestors did, once their celebrations were over. What has changed therefore is not so much the dress code for special occasions but rather the daily clothes of the Emberá, which are nowadays modern (e.g., shorts and T-shirts, for the men), or modern-and-indigenous combinations (e.g., paruma skirts matched with a top, for most women).

The implications of these transformations in Emberá clothing practices are undoubtedly countless. Particular dress choices relate to particular intentions—for example, a wish to either accentuate or temporarily deemphasize their indigeneity as the Emberá move between ethnically homogenous and multicultural contexts; relationships that the Emberá choose to pursue (with lovers, partners, relatives, indigenous or nonindigenous neighbors); subtle messages that can be only understood on culturally i...