- 230 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A History of Oxford Anthropology

About this book

Informative as well as entertaining, this volume offers many interesting facets of the first hundred years of anthropology at Oxford University.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A History of Oxford Anthropology by Peter Rivière in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

ORIGINS AND SURVIVALS:

TYLOR, BALFOUR AND THE PITT RIVERS MUSEUM

AND THEIR ROLE WITHIN ANTHROPOLOGY IN

OXFORD 1883–1905

AND THEIR ROLE WITHIN ANTHROPOLOGY IN

OXFORD 1883–1905

Any form of history is produced from contradictory motives. On the one hand, the historian attempts to be true to the past; to understand people and processes in their own terms, trying not to see events as the inevitable precursor of what we now know was to come. We should obviously resist the temptation to see the past purely through the lens of present concerns. On the other hand for history to be something more than a dilettante exercise it should speak to the concerns of the present, providing perspective and contrast to what is happening today. In this chapter we shall sketch the intellectual, institutional and personal situation of a nascent anthropology from 1883, outlining a very different organisation of knowledge to that which exists now and a university system that reflected this difference.

Anthropology at Oxford grew up initially as a minor element within the natural sciences, themselves still a small fraction of the University compared to classics and humanities. There were fierce debates on the benefits or otherwise of specialisation and the sciences generally grew up within the University Museum, partly designed to promote a unity of scientific endeavour. This is the past we shall attempt to understand in its own terms. But we shall also make two points of present relevance, both of them speculative. A theme running through the earliest history of anthropology within Oxford is the repeated failure to set up an undergraduate degree with anthropology as a major component. When these attempts did succeed, first with the establishment of the Human Sciences degree in 1969 and then with Archaeology and Anthropology in 1991, anthropology was set within a broad disciplinary compass which included variously the biological and social sciences, classics and archaeology. We wonder whether the birth of anthropology here, within a series of complex links to other disciplines, influenced its long-term history, making this eventual outcome less than an accident? Secondly, we are intrigued by the echoes resonating between a pre-disciplinary anthropology in the late nineteenth century and a situation developing in the present where disciplinary boundaries, so sharply erected and policed in the middle of the twentieth century, are starting to loosen up. We shall return to this point briefly at the end of this chapter.

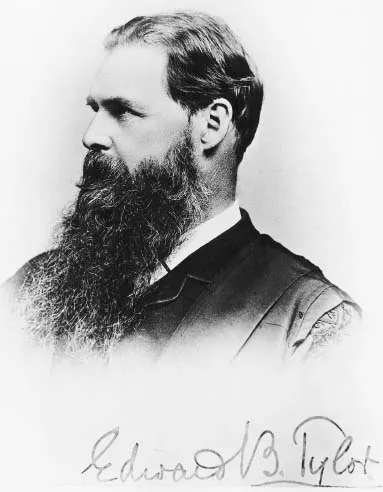

The period from 1883 when Edward Burnett Tylor took up his post as Keeper of the University Museum until 1905 with the formal start of the Diploma in Anthropology is a complex and ambiguous one. George Stocking referred to Tylor and his contemporaries as part of an ‘epistolary anthropology’, engaged as they were in letter-writing campaigns to bring ethnographic information from the colonial periphery to the metropolitan centres of academia. We shall refer to this period as one of material anthropology, letters being just one of the material supports for the early discipline. Anthropology in Oxford was built around the Pitt Rivers Museum, founded in 1884 as a department of the University Museum, which was completed in 1860 and designed to provide a single home for the natural sciences (physics, chemistry, biology, zoology and geology, to use present day labels).

Research and teaching were carried out within the Museum, and for both these activities the collections were crucial, expanding quickly beyond the 20,000 objects originally given in 1884 by the eponymous Pitt-Rivers. These collections consisted of anthropological and archaeological artefacts, supplemented, in 1886, by the transfer of material in the University and Ashmolean Museums deemed to be ethnological. The collections were painstakingly developed by Henry Balfour (with some new material also coming via Tylor). Balfour was employed initially for a year in 1885 and was made the first Curator of the Pitt Rivers Museum in 1890. The expansion of the collections at the Pitt Rivers Museum, through letter writing, travel and conversation, provided then the foundation for anthropology in Oxford and provides now a well-documented means of accessing this history. Balfour especially used the collections to give the Pitt Rivers Museum a separate status from the University Museum and this in turn helped differentiate anthropology as a subject within the broader ambit of the natural sciences. Balfour continued to use the Museum as both a research laboratory and as a political tool within the University until his death in 1939.

Figure 1. Edward Burnett Tylor circa 1880. Copyright Pitt Rivers Museum, 1998.267.88

The museum's collections also remind us that anthropology was a much more permeable and participatory discipline in the later nineteenth century than it is now. Material flooded in from all over the world sent by hundreds of people and often accompanied by letters or other forms of documentation pertaining to the use and history of the objects concerned.1 On numerous occasions artefacts were sent which had been solicited by either Tylor or Balfour, so that accompanying written material was penned in response to specific queries. The complex network of people (most of whom were not professional anthropologists), objects and written documentation helped form anthropology at the time and had a lasting historical impact. For those interested in these histories now, the museum and its collections represents a rich source of evidence which can indicate the social and material networks existing from the late nineteenth century onwards. Before taking a glimpse at some of this evidence, let us first outline some details relevant to Tylor's arrival in Oxford, the position of anthropology within the natural sciences and within the University Museum.

Earliest Anthropology and its Context at Oxford

Oxford, during the nineteenth century, saw a shift from a single core curriculum, taken by all students and based around classics, to various specialised degrees in which eventually no trace of Greek, Latin or ancient history remained. From 1850 it was possible to take new subjects as part of the BA, each with their own board of examiners, and these included natural science, law and modern history (Curthoys 1997: 352). Taking natural sciences generally added an extra year to the degree, which explains its relative lack of popularity. Also, the natural science degree lacked college tutors and fellows, and was mainly taught by readers and professors employed by the University and able to charge for attendance at their lectures. Generally speaking, attendance at science lectures was low, which made it more difficult to lobby for a greater provision for the sciences within the University. Through the 1850s Henry Acland (who became Regius Professor of Medicine) and others, including John Ruskin, lobbied for a central building for science facilities then spread throughout the larger and richer colleges. This campaign, which crystallised some of the key tensions between humanities and sciences at Oxford, was surprisingly successful, resulting in the building of the University Museum on land south of the University Parks. The Museum opened fully in 1862 and provided a setting where the major sciences of natural philosophy (physics), chemistry and physiology could each be provided with laboratory and teaching space, but also maintain some overall unity in accord with Acland's vision that the sciences should give an undergraduate a broad and comprehensive grounding in the working of the natural world (Fox 1997). The Museum was based around a central courtyard with each of the major subjects on the north, south, and west sides. The east side was left available for expansion. The teaching of natural sciences was henceforth based in the University Museum which had space for practicals within its laboratories and a lecture theatre.

Also, from the 1850s onwards Augustus Henry Lane Fox Pitt- Rivers started making a collection, first of firearms, in keeping with his early employment in the army, but soon branching out into ethnographic and archaeological artefacts. Influenced by moves to promote evolutionary thought after the publication of The Origin of Species in 1859, Pitt-Rivers ordered his collection so that it would exemplify general evolutionary principles, key amongst which was the movement from simplicity to complexity, which Pitt-Rivers felt to be fundamental to human history, as well as biological evolution. His collection was assembled not just for research purposes but also for education, especially the education of the working classes, and was exhibited first in Bethnal Green and then in the South Kensington Museum. Pitt-Rivers felt that each of these venues was unsatisfactory for his purposes and canvassed a range of options in an effort to find a more suitable location. He had a number of close contacts in Oxford, including Henry Acland and, especially, George Rolleston, the first holder of the new Linacre professorship of Anatomy and Physiology, based in the University Museum. Rolleston and Pitt-Rivers were personal friends who had travelled and done fieldwork together in Scandinavia and Britain (Chapman 1982: 192) and it was Rolleston who probably provided the initial impetus for Pitt-Rivers to consider Oxford as home for his collection. Rolleston died in 1881 before negotiations with the University could be completed. However, negotiations were taken up by John Obadiah Westwood, the Hope Professor of Zoology, and on 30 May 1882 the University accepted the offer of Pitt-Rivers’ collection: ‘That the offer of Major-General Pitt Rivers, F.R.S., to present his Anthropological Collection to the University be accepted…It will be seen that the Collection, besides having great intrinsic value, which from the scarcity of the objects themselves must necessarily increase as time goes on, it is of very wide interest, and cannot but prove most useful in an educational point of view to students of Anthropology, Archaeology, and indeed every branch of history.’ (Chapman 1984: 23).

Running in parallel with attempts by the science lobby in Oxford to convince Pitt-Rivers to give his collection to the University, was a campaign to attract Tylor to Oxford. Tylor had been awarded an honorary DCL in 1875, along with John Lubbock and others who promoted a Darwinian view of social progress. Rolleston's professorship was split up in 1884 and distributed between a Linacre Professorship of Human and Comparative Anatomy, the Waynflete Professorship of Physiology and a new Readership in Anthropology (Fox 1997: 688). This represented an expansion of anatomical and physiological teaching and research within the University, but also shows that anthropology was conceived of as contributing more broadly to comparative studies of the human body and its relationships to the environment. It is also fitting that Rolleston, a great promoter of ethnology during his life, opened the way for the first post in the subject through his early death. Tylor was given first the Keepership of the University Museum in 1883 and then the Readership in Anthropology in 1884, starting his first formal lectures within the University in that year. Thus the ultimate beginnings of anthropology in Oxford date to 1884.

Tylor's duties were ill-defined, but probably included some responsibility for all the collections and activities of the University Museum, of which the Pitt Rivers Museum became a part. A new building was constructed to house this collection on the eastern side of the University Museum court. Work on the new building only began in 1885, and so the initial unpacking of the Pitt Rivers collection took place in the University Museum itself. Tylor had no special responsibility for the Pitt Rivers collection, which was managed by Henry Nottidge Moseley, the Linacre Professor of Human and Comparative Anatomy (a post created out of Rolleston's old chair). Moseley was responsible for unpacking and arranging the Pitt Rivers collection, while Tylor had an oversight role as Keeper of the Museum as a whole. When the collection was transferred from South Kensington Museum in 1884, Walter Baldwin Spencer was employed to help with the process. He was a natural sciences graduate, closely associated with Moseley, and was later to use the experience he gained from this close contact with a wide range of artefacts to good effect in his groundbreaking fieldwork in central Australia. Spencer commented of this time:

[I]t was the old Pitt Rivers collection that first gave me my real interest in Anthropology…. I did a great deal of the packing up and it was intensely interesting to have Moseley and Tylor coming in and hear them talking about things. I remember well that Moseley seemed to know a great deal more than Tylor in regard to detail and, of course, after his experience on the ‘Challenger’ he could speak of many things with first hand knowledge but Tylor with his curious way which you may remember of every now and then as it were ‘drawing in his breath’ – I don't know how otherwise to express it – simply fascinated me. It was intensely interesting to a young man like myself and also a great privilege to come into such personal contact with two such workers. Of the two it struck me at that time that Moseley had the greater technical knowledge but Tylor the wider outlook (PRM MS Collections, Spencer papers, Box IV: letter 21, 24 September 1920).

In October 1885, Moseley wrote to one of his former tutees in natural science, and a contemporary of Spencer's, Henry Balfour, to ask whether he could assist for one year in the unpacking of the collection, for which he would be paid £100. This temporary proposal became the start of Balfour's fifty-three year association with the Museum ending with his death in 1939, aged seventy-five. Balfour had read natural sciences at Trinity between 1882 and 1885, much of the teaching for which took place in the University Museum, using its collections. He fitted well into the general natural science ethos within which anthropology was created in Oxford and was disposed to think of the Pitt Rivers collection as an extension of the insects, fossils, human skeletal remains, plants, animals and minerals that composed the collections of the wider Museum.

In this respect, his approach mirrored that of other anthropologists in the same generation. Alfred Cort Haddon, for example, was a trained zoologist whose ethnographic research in the field and at home was, in many ways, an extension of his work as a marine biologist (Herle 1998). Large, systematic collections of specimens, which could be assembled, classified and analysed in great detail, were at the heart of research in the natural sciences at this time. Haddon and Balfour saw themselves as observational scientists, bringing their skills to bear on evidence for human cultural diversity and history. Other anthropologists within the Cambridge School, such as William Halse Rivers and Charles Gabriel Seligman, worked in the tradition of experimental science, conducting sensory and psychological tests on their subjects in the field. Collecting and evaluating objects was fundamental to this form of anthropology, which was so preoccupied with gathering ethnographic ‘facts’. Whether working in the museum, surrounded by artefacts and specimens, or amongst indigenous informants far from home, this ‘intermediate’ generation of ethnographers sought to create a science out of culture and its products.

Balfour's work was firmly focused on the Museum in Oxford from an early stage in his career. When Moseley was forced into early retirement due to ill health in 1887, Balfour took sole responsibility for the collections, lobbying Convocation for more salary for himself and greater financial support for the collection. Balfour was at pains to stress in various forms of extant correspondence that he, not Tylor, was in charge of the collection and that only he was genuinely knowledgeable about the specimens and their manner of arrangement. Balfour was almost unknown during the 1880s and still in his twenties, whilst Tylor was the best known anthropologist in the English-speaking world. It is unsurprising that people inside the University, and without, should have associated Tylor's name with the creation of the collection, but Balfour was understandably irked by the fact that his hard work was not properly recognised and acknowledged. Through the 1880s and 1890s Balfour pursued a vigorous and generally successful campaign in the University to lobby for more resources for the Pitt Rivers collection and to have himself acknowledged as its first Curator. He was recognised in this title in 1890 and from then on the Museum started to separate from the Anatomy Department and from the University Museum more generally. Balfour not only created a job for himself, but provided ethnology with an increasingly separate status inside the University. This status remained ambiguous and disputable through into the early decades of the twentieth century (see Rivière, this book), but the existence of anthropology as a subject was made tangible and real through the growing bulk of the Museum's collections and the activities carried out through these collections. The transfer of ethnological material from the University Museum and the Ashmolean in 1886 was another significant step in the University's recognition of anthropology.

In June 1895 anthropology's profile was enhanced when a statute was approved to establish a Professorship of Anthropology for Tylor, tenable for the duration of his readership. According to the University Gazette, Balfour gave his first official series of lectures to students during the Michaelmas Term of 1893 (although he had taught students informally prior to this date). He talked on the ‘Arts of Mankind’ and used objects from the Pitt Rivers Museum collections to illustrate his words. As Reader in Anthropology, Tylor had been giving a series of anthropology lectures every term since January 1884, but in 1893 his lectures were announced in the Gazette alongside Balfour's and another series devoted to physical anthropology to be given by Arthur Thomson, then Lecturer in (soon to become Professor of) Human Anatomy. A special notice announced that, while they were open to anyone who was interested, all these lectures were ‘adapted to meet the requirements of Students taking up Anthropology as a Special Honour Subject’ at the University (OUG 1893: 603). This teaching continued into the early twentieth century when Balfour and Thomson were joined by Marett, together becoming known as ‘the triumvirate’ by successive generations of anthropology students. These three remained responsible for the University's core teaching in anthropology until the 1930s.

Tylor led a petition to establish a FHS in anthropology at Oxford, which culminated in 1895, but Convocation rejected his proposal, something he felt bitter about throughout his life. John Linton Myres (1953: 7) remembered that Tylor

resented the rejection of his project for a degree examination in anthropology. It was an unholy alliance he said, between Theology, Literae Humaniores, and Natural Sciences. Theology, teaching the True God, objected to false gods; Literae Humaniores knew only the cultures of Greece and Rome; Natural Sciences were afraid that the new learning would empty their lecture rooms. And the arch-villain was Spooner of New College, whom he never forgave.

Anthropology could only be taken as a special subject within the FHS of Natural Science, and this remained the case for undergraduate teaching until the first intake of Human Sciences undergraduates in 1970. One can speculate as to why anthropology failed to gain final honour school status, but part of its failure must be due to Tylor's lack of ability to galvanise support within the University. Although a popular and respected figure in the institution, Tylor seems not to have viewed the University as the sole centre of his life – he and his wife Anna took the train to Anna's family home in Wellington, Somerset, at the end of every term, only to return at the beginning of the next term. They spent under half the year in Oxford. Furthermore, Tylor lacked a college base (common for readers and professors at this time) until he received an honorary fellowship at Balliol in 1903, which reduced his ability to link into significant parts of the collegiate University. This might have been significant in his failure to convince the body of college tutors that anthropology was a suitable subject for undergraduate study.

In 1896 Tylor was unwell and underwent operations on 16 and 30 June. He seems from this point to have...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Contributors

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1. Origins and Survivals: Tylor, Balfour and the Pitt Rivers Museum and their Role within Anthropology in Oxford 1883–1905

- 2. The Formative Years: The Committee for Anthropology 1905–38

- 3. How all Souls Got its Anthropologist

- 4. A Major Disaster to Anthropology? Oxford and Alfred Reginald Radcliffe-Brown

- 5. ‘A Feeling for form and Pattern, and a Touch of Genius’: E-P's Vision and the Institute 1946–70

- 6. Oxford and Biological Anthropology

- 7. Oxford Anthropology as an Extra-Curricular Activity: OUAS and JASO

- 8. Oxford Anthropology Since 1970: Through Schismogenesis to a New Testament

- Appendix: Reflections on Oxford's Global Links

- Bibliography

- Index