![]()

CHAPTER 1

From Participant to Observer: Autobiographical Discourse in the Films of Jerzy Skolimowski

In his native Poland, Skolimowski is regarded as an artist who has conveyed his life and persona on screen more effectively than any other Polish film maker: the ultimate autobiographer in and for Polish cinema. This chapter attempts to establish how Skolimowski managed to convince his viewers that his films are about him, and how his self-portrait evolved over the years. Before I move to discussing Skolimowski's films and his life, it is worth briefly presenting the concept of autobiography I will use. I regard autobiography not so much as a matter of truthful representation of one's persona and life, but of the impression effected by the autobiographer on his reader (see Pascal 1960; Buckley 1984; Lejeune 1989). Accordingly, it is always relative, depending, for example, on the form used by the writer and the moment an autobiography is created and assessed. Lejeune uses the term ‘autobiographical pact’ but I would prefer to use the term ‘autobiographical effect’ because ‘pact’ suggests conscious decisions on the part of writer and reader to write and read a particular work as autobiographical. In reality, ‘autobiographical reading’ is usually involuntary, almost automatic. Moreover, as I argued elsewhere (see Mazierska and Rascaroli 2004; Mazierska 2007), ‘autobiographical effect’ is never solely the product of a particular work of art which mirrors somebody's life, but also a product of using one's creative work to shape one's life. As Polish philosopher, Szymon Wróbel, observes, establishing whether a work of art is an autobiography ultimately means matching one partial and subjective representation (autobiography) with another which is also partial and subjective (life). Stuart Hall presents a similar argument, maintaining that ‘rather than speaking of identity as a finished thing, we should speak of identification, and see it as an on-going process. Identity arises, not so much from the fullness of identity which is already inside us as individuals, but from a lack of wholeness which is “filled” from outside us, by the ways we imagine ourselves to be seen by others’ (Hall 1992: 287–88).

Skolimowski – Life and Fiction

Although Hall's and Wróbel's observations are valid in reference to every artist and every man, they ring particularly true in relation to Skolimowski, because in his case the web of life, narration and artistic creativity is extremely complex. I believe that Skolimowski used cinema (which includes, for example, interviews he gave) to create and test his different personas and correct the official version of himself; to share with the public his private life and even, perhaps, to communicate with those closest to him, his family and friends, in a way he could not achieve off-screen. Cinema also made Skolimowski, bringing him fame, assuring him the status of a ‘cult director’ and a major legend of Polish cinema. On the other hand, it severed him from his Polish roots and changed him into a migrant. After projecting on screen a certain image of himself, the director had to live up to this image in his private life, which in later instances affected his films.

To illustrate this mutual relation between life and work I would like to mention three episodes from Skolimowski's biography. The first incident concerns the fate of his fourth full-length feature film made in Poland, Hands Up! An important element of its mise-en-scène is a huge portrait of Stalin with two pairs of eyes. The contentious character of this image led to the censors’ demand to cut from the film any footage including it. Skolimowski rejected this request, which led to much unpleasantness from the political authorities, including from Zenon Kliszko, the Party official, regarded as the second most important person in Polish politics at the time, after the First Secretary, Władysław Gomułka. The director, however, did not give in and, finally, as he himself confessed in a television interview broadcast many years later, he was offered a passport, which amounted to an invitation to leave Poland. He emigrated, to live life and make films that were without doubt very different from those he previously made in Poland. It is plausible to assume that even if Hands Up! had been Skolimowski's first film, he would have acted in the same principled way with the political authorities. It can also be suggested that his reputation as the chief nonconformist of Polish cinema was a factor in his resolute rejection of the offer to compromise. If he had accepted it, he might have saved his film and continued to make films in socialist Poland, even becoming its leading director, but he would have destroyed the rebellious persona he created in his previous films and in this one. When Hands Up! was eventually taken from the shelf in 1981, rather than allowing it to be released in its original version Skolimowski added to it a prologue (or rather Prologue with capital P, because it functions almost like a film in its own right), in which he explains the circumstances in which this film was banned in Poland, as well as describing his life concurrent to the period of Hands Up!'s belated release. It thus appears as if the director cannot accept any dissonance between his films and his biography – the films always have to be in step with his life.

The second episode concerns Skolimowski's age. According to official documents, he was born in 1936. This date is also ‘confirmed’ in Walkover (1966), in which the main protagonist is about to celebrate his thirtieth birthday. However, in an interview given in Filmówka, a book commemorating the history of the famous Łódź Film School, as well as in our talk, Skolimowski presents himself as being two years younger than his birth certificate proclaims. The disparity between his real and official age apparently resulted from his poor physical state after the end of the war. The mother of the future director, wanting to save him, falsified his birth certificate, thanks to which he could go to convalesce in Switzerland (see Krubski et al. 1998: 73). The story of Skolimowski's contentious age can be regarded as trivial, but I find it symbolic of the character and status of Skolimowski's cinema, as well as of his place in Polish culture. Having two dates of birth (official and unofficial but based on personal testimony) seems fitting, given Skolimowski's position as somebody who, thanks to his films, has more than one persona or ‘mask’, and who can use his power of narration to correct his life. Skolimowski's ‘rejuvenation’ by subtracting two years from his life, using narration, brings to mind old film stars who wanted to be regarded as younger than they were according to official documents (Pola Negri apparently had several dates of birth). More importantly, it increases the temporal distance between Skolimowski and the war generation. Having been one year old when the war began, the future director was not only excluded from anti-Nazi resistance, but could not even have any significant memory of the war. Not remembering wartime is an important trait of Skolimowski's protagonists in films such as Identification Marks: None and Barrier, distinguishing them from the generation of war veterans. By presenting himself as somebody who is two years younger, Skolimowski thus increases the similarity between himself and his protagonists. Finally, the story of a wrong date on an official document excellently conveys Skolimowski's distrust of officialdom, especially of any documents produced in socialist Poland. Again, this is also a motif present in many of his films, most importantly in Identification Marks: None and Hands Up! I must emphasise that I am talking here only about the associations the story of the ‘wrong date of birth’ has for me, without assessing its authenticity, something I am unable to do.

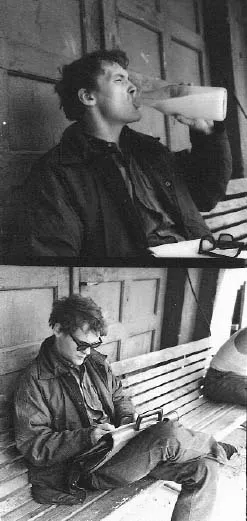

Figure 1.1 Jerzy Skolimowski during shooting Hands Up!

The third episode refers to the director's relation with Elżbieta Czyżewska, who was perhaps the greatest Polish female star of the 1960s. This actress played in Skolimowski's short films, Little Hamlet and Erotyk, as well as in Identification Marks: None and Walkover, where her presence, however, is reduced to a photographic image. These films trace the development of the director's relationship with Czyżewska, from youthful interest in Little Hamlet, through erotic fascination in Erotyk, to a more complex, multidimensional relationship in Identification Marks: None and, finally, separation and her fading away from the director's memory in Walkover. They also mirror a certain ambiguity of this relationship, which is lacking from Skolimowski's relationship with Joanna Szczerbic, his later wife, as represented on and off the screen. In particular, we never learn whether Teresa in Identification Marks: None is Leszczyc's wife or only plays this role. Similarly, most critics claim that Czyżewska and Skolimowski were married, while in interviews Skolimowski denies this claim and is generally rather taciturn about this chapter of his private life (see Lichocka 1994: 7). Indeed, if the director and the actress never married, then do the critics attribute to him something which they learnt about his cinematic creation, Andrzej Leszczyc? Or, perhaps, it is rather Skolimowski who follows Leszczyc in denying Czyżewska any important role in his life? Again, I do not have answers to these questions and they do not interest me very much. I ask them only to draw attention to the complex mesh of life and fiction in Skolimowski's case.

The presence of autobiographical discourse both links and distinguishes Skolimowski from Roman Polański. The films of both directors lend themselves to autobiographical reading, as both engage with such issues as the condition of an emigrant. Both directors also tended to cast their wives in their films. However, prior to making The Pianist, Polański never revealed any desire to make films about his life and vigorously distanced himself from any attempt by the critics to see in his characters his hidden persona. By contrast, Skolimowski consciously and openly created his characters in his own image. Polański is thus a film maker who draws on his life to furnish his characters and stories with authenticity. Skolimowski is a compulsive autobiographer who uses film as a medium to tell different versions of his own story.

Autobiographer as Participant

It is widely agreed that Skolimowski's four early Polish films: Identification Marks: None, Walkover, Barrier and Hands Up!, produce the strongest autobiographical effect of all the films he ever made. However, it is worth grouping them together with Wajda's Innocent Sorcerers and Polański's Knife in the Water, as they project a somehow similar image of the protagonist. As is documented both by Wajda and Skolimowski, Wajda invited Skolimowski to collaborate on his film because it was meant to depict the lives of young people, and by this time the future director of Barrier was already regarded as a specialist in this topic (see Wertenstein 1991: 42). Skolimowski fulfilled this expectation by choosing as the main character a young man sharing his interests in jazz, boxing and pretty women, and reserving for himself a small role as a young boxer. Wajda was not content with the overall effect, but not because Skolimowski's vision dominated the film, but because it did not come across more forcefully. He claimed that the effect would have been much better if the central couple were played by Skolimowski himself and Czyżewska, who were the true ‘innocent sorcerers’ of those times (ibid: 42). Most likely Wajda came to this view retrospectively, by watching films in which his younger colleague played main roles. His reasoning appears to be that Skolimowski's work is by ‘its nature’ autobiographical; therefore, to make use of his talent one should allow his autobiography to prevail, through using his own body, so to speak. A similar argument is presented by Mariola Jankun-Dopartowa, who claims that Barrier is a flawed film because Skolimowski does not play its protagonist (see Jankun-Dopartowa 1997: 100). In common with Innocent Sorcerers, Skolimowski joined the team of people writing a script for Polański's Knife in the Water and contributed to it immensely (see Polanski 1984: 133) because he knew the idiom of the young generation to which the film's main character belongs – it was his own idiom. Consequently, the Student in Knife in the Water, like Skolimowski, has blond hair, and shows no respect for the older generation (see Uszyński 1990a: 8), although he is a ‘composite’ character, bearing similarity both to Skolimowski and Polański.

The autobiographical effect is much stronger in the films which Skolimowski himself directed. The most obvious reason for that is the director playing the main part in three of them and having the same name in all three – Andrzej Leszczyc. The main character of Barrier is played by Jan Nowicki and does not have a name; instead, he is described in the script as the ‘Boy’. However, the director offers enough hints within the film's diegesis and off-screen to allow many viewers and critics to regard the Boy as a variation of the character of Leszczyc and Barrier as a part of the ‘Leszczyc tetralogy’. The most important was his desire to play in this film; he could not because of pressure the political authorities exerted on him not to do so.

Skolimowski explains that he cast himself in Identification Marks: None largely because of the unorthodox way the film was made. Assembled from short films he shot during his study at the Łódź Film School as students’ exercises, it was made for so long and in such difficult circumstances that it would be next to impossible to employ a professional actor because hardly any actor would agree to play ‘on demand’ and practically for free (see Krubski et al. 1998: 149). The very difficulty of making Identification Marks: None instantly set it apart from the rest of Polish film production. This film was perceived as, in a sense, more than a film – a personal project, even a way of living, and over forty years after its premiere it has not lost any of its uniqueness (see Ronduda 2007). Again, this impression was confirmed by the director, who claimed that if it were not for making Identification Marks: None, he would not have persevered with his years as a student in the Łódź Film School (see Ziółkowski 1967: 9). As Walkover continued Leszczyc's adventures, it was natural that he again cast himself in the main role. Leszczyc in Walkover is older than in Identification Marks: None and has already gone through some of the experiences mentioned in the first films, most importantly expulsion from the university where he studied engineering, military service and testing himself in sport. In Hands Up!, Leszczyc is even older and, again, he was once expelled from university, although this time from medical school. In Barrier, although it was shot after Walkover, the main character appears to be younger than Leszczyc in the earlier film, and he is again at university, although about to leave. We see that some details of Leszczyc's life are mutually exclusive, but the general picture in terms of biographical details and character's traits is coherent (see Walker 1970: 39). Most importantly, Leszczyc is partly a rebel, partly a drifter, but neither to an extent which would preclude his future integration to society. It is even possible to construe him as a conformist (see Ronduda 2007).

The cumulative effect of playing a similar character, furnished with the director's physicality, was more important in creating an autobiographical effect than attributing to Leszczyc the adventures and personal traits of the ‘real’ Skolimowski. Had Skolimowski played Leszczyc only once, the effect would be much weaker, even if his incarnation had more in common with him. Similarly, if in Identification Marks: None a different actor was cast, it would be difficult to link this film with the following three, even if Skolimowski played in them. The ‘Andrzej Leszczyc effect’ can be compared here with the ‘Antoine Doinel’ effect in the films of François Truffaut, except that the autobiographical effect of the films of the Polish director is stronger because, unlike Truffaut, Skolimowski played his alter ego.

Paradoxically, the impression that we watch the director's autobiography in the ‘Leszczyc tetralogy’ was also facilitated by a certain sketchiness of the main character. As Konrad Eberhardt observes, Leszczyc is more ‘opaque’ than his counterparts in the films which Skolimowski only scripted. We know less about him than about the Student from Polański's Knife in the Water and Bazyli from Innocent Sorcerers (see Eberhardt 1982: 116). Janusz Gazda refers to the same feature, describing Leszczyc as ‘abstract’ (Gazda 1967b: 3). The consequences of Leszczyc's sketchiness are twofold. Firstly, thanks to being only a ‘skeleton’, Leszczyc can accommodate different ‘bodies’: be a somehow disorientated, anti-consumerist and polite man (at least when dealing with officialdom) in Identification Marks: None, and a materialist and arrogant Boy in Barrier. Secondly, opaqueness and elusiveness set Leszczyc apart from the bulk of the characters of earlier Polish cinema which favoured more ‘definite’ characters over those who are always in a state of becoming.

In his ‘Leszczyc films’, as well as in the etudes shot before embarking on Identification Marks: None, Skolimowski used his relatives and friends, most importantly, his two girlfriends, Elżbieta Czyżewska and Joanna Szczerbic (who later became his wife), in the roles of girlfriends of the main characters. While watching these four movies we witness the development of the director's involvement with these two women. I have already mentioned the trajectory of Czyżewska's character from the early shorts to Walkover. In Walkover, Leszczyc looks for a new woman and finds her in Teresa, played by Aleksandra Zawieruszanka, but for a number of reasons their relationship is unsatisfactory. Only in Barrier does he appear to find his true match – a young tram driver, played by Szczerbic. The testimony of her importance is the fact that, unlike in previous films, the female character is granted some narrative autonomy (see Kornacki 2004), because for a while the camera leaves Leszczyc and follows the driver. However, as I will argue in the following chapter, this is not matched by her psychological autonomy – she is all for her Boy. In Hands Up!, Szczerbic's character, now named Alfa, is friendly ...