eBook - ePub

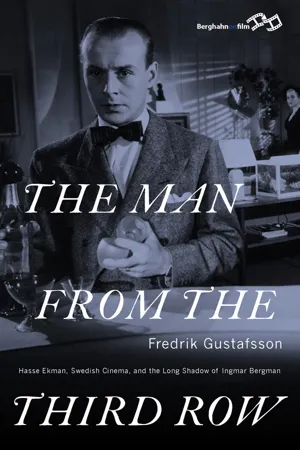

The Man from the Third Row

Hasse Ekman, Swedish Cinema and the Long Shadow of Ingmar Bergman

- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Man from the Third Row

Hasse Ekman, Swedish Cinema and the Long Shadow of Ingmar Bergman

About this book

Until his early retirement at age 50, Hasse Ekman was one of the leading lights of Swedish cinema, an actor, writer, and director of prodigious talents. Yet today his work is virtually unknown outside of Sweden, eclipsed by the filmography of his occasional collaborator (and frequent rival) Ingmar Bergman. This comprehensive introduction—the first ever in English—follows Ekman's career from his early days as a film journalist, through landmark films such as Girl with Hyacinths (1950), to his retirement amid exhaustion and disillusionment. Combining historical context with insightful analyses of Ekman's styles and themes, this long overdue study considerably enriches our understanding of Swedish film history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Man from the Third Row by Fredrik Gustafsson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

On Auteurs and National Cinema

Although discussing the films of Hasse Ekman within the context of Swedish national cinema, this is primarily a straightforward study of an auteur. The main reason for this approach is that this is the first English-language study of Ekman’s films, and should therefore cover all the films with which he was involved, focusing on his particular contribution to them and to Swedish cinema in general. This study will provide a foundation for further discussions of individual films and aspects of his career from various theoretical standpoints and towards the end of the book there will be suggestions for other angles from which to continue to explore and analyse Ekman’s body of work.

But since the concept of auteurs, or auteurism, is much contested would it not be better to disregard it? Some believe so and consider it a romantic delusion, or obsolete in the context of contemporary cinema studies. As Catherine Grant has argued, ‘film authorship has rarely been considered a wholly legitimate object of contemplation’ (Grant 2000: 101). So is the term ‘auteur’ really necessary? Is not cinema a collaborative art form? Might not the word ‘filmmaker’ suffice instead, or perhaps just ‘director’, as they are not questioned in the same way as ‘auteur’ is? But there is a difference between ‘filmmaker’, ‘director’ and ‘auteur’. A person who makes educational films, or public relations films, is a filmmaker but hardly ever an auteur. A director likewise. A director might not have had a hand in the development of the script but an auteur almost always has. And it is precisely because cinema is a collaborative art form that it is relevant to speak about auteurs. Films are made by a number of people but they are not all of equal importance for the finished result.

Thinking about auteurs is not new with regards to filmmaking: it was happening almost right at the beginning of film history, even though it is sometimes assumed that it first came about in the mid-1950s. The following section will emphasise this historical background, and also specify the way in which ‘auteur’ is defined and used in this book, precisely because it is a contested term and has been defined in many different ways.

When talking about authorship and auteurs it is customary to begin in France in the 1950s with the writings of Alexandre Astruc, André Bazin, François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard and others. Film History – An Introduction (Bordwell & Thompson 2003: 415–417), The Film Experience – An Introduction (Corrigan & White 2009: 465–466) and Approaches to Popular Film (Hollows & Jancovich 1995: 37–58) are examples of books that place the emergence of ideas about directors as auteurs in France at this time. But this is to some extent ahistorical since already by the beginning of the twentieth century there was a particular focus on the director in cinema. Traditionally, film has been seen as the director’s medium, not least from a marketing perspective. The poster for the US film Intolerance (1916) is an example of this. Despite the fact that some of Hollywood’s most famous stars at the time, such as Lillian Gish and Mae Marsh, acted in the film, the name used to sell it was that of its director, D.W. Griffith. The poster also makes a direct reference to a previous film by Griffith. The words on the poster, directly below the film title, are ‘Mr Griffith’s first production since “The Birth of a Nation”’. Using only the name of the director, however, was still rather unusual. Usually, the director and the names of some of the more famous actors would be used, such as on the poster for the first version of Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1925): the name of the director, Fred Niblo, comes first, and in slightly bigger letters than the names of the actors. For a typical Swedish example, the poster for The Phantom Carriage (Körkarlen, 1921) is illustrative. Beneath a drawing of the eponymous carriage it reads: ‘Selma Lagerlöf’s The Phantom Carriage told in moving images by Victor Sjöström’ (trans.). The selling point was definitely the authors behind it: Lagerlöf, who wrote the short story, and Sjöström, who directed the film. On the poster for Hasse Ekman’s first film, With You in My Arms (Med dej i mina armar, 1940) it says ‘Direction: Hasse Ekman’ (trans.) as an enticement to the audience.

These examples have focused mainly on the marketing perspective and it should also be added that film trailers often used the director’s name as a selling point, the director sometimes even appearing in the trailer. Of course, it was not only the publicity departments that were promoting the director above other members of the crew. In early film theory, films were also often attributed to their directors, as in this passage by Jean Epstein written in the 1920s:

But the proper sensibility, by which I mean a personal one, can direct the lens towards increasingly valuable discoveries. This is the role of an author of film, commonly called a film director. Of course a landscape filmed by one of the forty or four hundred directors devoid of personality whom God sent to plague the cinema as He once sent the locusts into Egypt looks exactly like this same landscape filmed by any other of these locust filmmakers. But this landscape or this fragment of drama staged by someone like Gance will look nothing like what would be seen through the eyes and heart of a Griffith or a L’Herbier. And so the personality, the soul, the poetry of certain men invaded the cinema. (Epstein 1988: 317–318)

Since Epstein was writing in French, he of course used the word auteur, which here was translated into ‘author’. He unequivocally equates the author with the director, and for him this is an important aspect of what makes cinema an art form.

Another theorist writing in the 1920s, Louis Delluc, wrote about the director as the unifying force and argued that the director, if he is good enough, is the genius behind the film and is even, if he is as brilliant as Thomas Ince, capable of creating a masterpiece out of nothing (cited in McCreary 1976). Vachel Lindsay is yet another early example of a theorist who championed the notion of the ‘auteur’ (Lindsay 2000). One of Britain’s leading twentieth-century film critics, Dilys Powell, had what might be called an auteurist approach, at least from the beginning of the 1930s. When she wrote, in the 1930s and 1940s, about individual films by the likes of Carol Reed, Alfred Hitchcock, John Ford and Fritz Lang, she frequently discussed those films as being part of each director’s larger body of work. In 1946 she talked about the national, industrial and cooperative aspects of cinema and then asked the rhetorical question: ‘How can one man leave the mark of his personality and his talent on this hugger-mugger?’ and she answered, ‘But he does’ (Powell 1991: 37). In Sweden in the early 1940s there was a debate among film critics and scholars about who should be considered the true author of a film. There were those who said that it should be the writer and those who said it should be the director. In a summary of the debate the critic Georg Svensson came down firmly on the side of the director (Svensson 1941), in an article that would not have been out of place in an issue of Cahiers du cinéma, some fifteen years later.

In other words, directors, since the early days of cinema, have often been seen as the main force behind a film, the artist making it, by both critics and theorists. And the publicity departments used the name of the director as a selling point, which seems to suggest that for the public too it was the director who counted most, together with the actors. These ideas were then amplified in the 1950s and 1960s, especially in France (Cahiers du cinéma), in the UK (from 1962 in Movie) and in the USA, especially through the writings of the critic Andrew Sarris. At this point, it came to be known as the ‘auteur theory’. However, it should be stressed that, although often used, the term ‘auteur theory’ is questionable. Even Sarris, who wrote extensively about it and helped make the idea popular in the US, said that it was not a theory as such and that: ‘[u]ltimately the auteur theory is not so much a theory as an attitude’ (Sarris 1968: 30). It is rather a critical approach, or, as Robert Stam would have it, a ‘methodological focus’ (Stam 2000: 91). In this study the term auteurism is used instead.

The strong reactions against the idea of the auteur, and authors in general, emerged especially in the late 1960s and the 1970s (see for example Heath 1973; Foucault 1977; Kael 2007). Some of the criticism came from structuralists and post-structuralists, who argued that the author is not important but should be seen as merely a mediator between the text and the audience (Stam 2000: 123–125). The author might even, as in Roland Barthes’s famous essay from 1967, be declared dead. Barthes is concerned with language, which for him is the central creator of meaning: ‘it is language which speaks, not the author’ (Barthes 1977: 143). By ‘killing off’ the author, as it were, the text is liberated and becomes open to the reader’s own ideas and interpretations, and in a sense the text is created when it is being read. However, three years later Barthes opened up the possibility that the author might actually be alive in the text. In the essay ‘From Work to Text’ he wrote that: ‘It is not that the Author may not “come back” in the Text, in his text, but he then does so as a “guest”. If he is a novelist, he is inscribed in the novel like one of his characters’ (Barthes 1977: 161). When Barthes wrote about films his writing was usually focused on the director, his skills and intentions. In an article in Le Monde about the film French Provincial (Souvenirs d’en France, André Téchiné, 1975) Barthes wrote: ‘With Téchiné comes lightness: this is a significant event not just for the theory of film-making but also for the practice of film-watching’ (quoted in Calvet 1994: 193). This seems to suggest not only that the author is alive, but also that the director is significant. Barthes has also written, favourably, about Sergei Eisenstein, Charles Chaplin and others (Barthes 1994), so maybe the auteur never was dead, not even for Barthes.

In the article by Catherine Grant mentioned earlier she emphasises towards the end that the auteur will not go away, and that there are good reasons for this. She mentions for example the importance of auteurs within cinephilia and also how minorities, be it sexual or ethnic, have stressed the importance of gay filmmakers, filmmakers with immigrant backgrounds or members of some other minority group. ‘An academic commerce in auteurism, then, continues apace, hardly touched by the earlier debates, except perhaps that many more previously marginal auteurial “subjects” are invited for discussion (women, gays, non-white, non-western filmmakers, and so on)’ (Grant 2000: 108).

In recent times Dorothy Arzner, an early female filmmaker in the Hollywood studio system (when it was very rare to find women in such a position), is one of many who have been ‘discovered’ (see, for instance, Johnston 1975); another example of this trend is Christina Lane’s research on the writer/producer Joan Harrison (Lane 2003). There are also now several studies of queer filmmakers, such as Michael DeAngelis’ work on Todd Haynes within New Queer Cinema (DeAngelis 2006). Such work points to the relevance of auteur studies from a perspective of equality and progressiveness or what James Naremore refers to as ‘an attack on convention and a form of resistance’. He also argues that auteur studies have the ability to explore, expand and challenge canons and previous thinking about film history (Naremore 2014: 31–32) and that idea is partly what inspired this study of Hasse Ekman.

Today there is a common expression in film criticism which has taken the notion of the auteur to a different level. It is the expression ‘auteur cinema’. In a way it is the opposite of traditional auteurism, even though the terms are frequently used synonymously. ‘Auteur cinema’ is often put in opposition to commercial cinema, and by doing so the difference between ‘auteur cinema’ and traditional auteurism becomes clear, since auteurists, such as Andrew Sarris, were arguing that there was no contradiction between auteurs and commercial cinema and that auteurs were in fact plentiful in commercial cinema. So ‘auteur cinema’ is an unhelpful term. It is often used as a marketing device at film festivals and by arthouse cinemas to distinguish their films from the mainstream cinema, as if mainstream cinema could not possess auteurs. It is sometimes said against auteurism that it is a romantic idea, as when Linda Haverty Rugg argues that the concept of the auteur is ‘imbued with romantic notions of artistic genius’ (Rugg 2005: 228–229). That is a valid criticism of the concept of ‘auteur cinema’, because it suggests films that are made by creative geniuses beyond genres and commerce. But it is not a valid criticism against auteurs as such, in the way that the concept is used in this book.

Films can be analysed from an economic perspective, an industrial perspective or an audience perspective. But, whilst important, such perspectives will not fully explain why a particular, individual film was made and neither will it explain what the particular circumstances were in which that film was made. This is something important that auteurism brings to the study of cinema. Part of history and its progress are ideas and emotions, and these originate in human beings. This is naturally true for film history as well. By not discussing the actual people making the films, an important part of film history goes missing, and it will not be possible to gain a complete understanding of that history. In the introduction to his book on Luchino Visconti, Geoffrey Nowell-Smith writes:

As a principle of method the [auteur] theory requires the critic to recognize the basic fact, which is that the author exists, and to organize his analysis of the work around that fact. Whether one is trying to get to grips with a particular film, or to understand the cinema in general, let alone when one is studying the development of an individual director, the concept of authorship provides a necessary dimension without which the picture cannot be complete. … [O]ne essential corollary of the theory as it has been developed is the discovery that the defining characteristics of an author’s work are not always those that are most readily apparent. (Nowell-Smith 2003: 10)

The key point here is that ‘the author exists’. S/he is not something that can be theorised away. Films are made by individuals, individuals who think, act and make conscious decisions: they are independent agents, and to quote Torben Grodal, ‘It is fundamental for normal human functioning that our theory of other minds acknowledges that such minds belong to conscious, intending, and desiring beings’ (Grodal 2004: 15).

However, there are more agents than just directors on a film set and the automatic focus on the director can be problematic. Scriptwriters and cinematographers tend to be overlooked, as well as other contributors. It is quite obvious, for example, how Michael Powell has been given much more attention than Emeric Pressburger, despite the fact that they worked as an intimate team. (Interestingly, there are a number of such teams in British cinema. Other examples are the Boulting Brothers, Basil Dearden/Michael Relph and Frank Launder/Sidney Gilliat.) In Our Films, Their Films Satyajit Ray wrote:

A director weak on the visual side may be considerably helped by a cameraman with a sense of drama. When a director is a true auteur – that is, if he controls every aspect of production – then the cameraman is obliged to perform an interpretative role. Whenever he does more than that, the director should humbly part with some of his credit as an auteur. (Ray 1994: 68)

This seems only reasonable, and not only with regard to the camera operator, but also with scriptwriters, set designers and composers. Paul Coates calls these other participants ‘mini-auteurs’ (Coates 1985: 83). The critic and the scholar should see to it that credit is shared, stressing the importance of co-workers and companions, of writers, cinematographers, producers and actors, in the making of the films being considered. Even so in most cases the director is still the central force on the set – the person who is responsible for the whole of the film. As V.F. Perkins wrote in Film as Film, ‘The director’s authority is a matter not of total creation but of sufficient control’ (Perkins 1993: 184); the word ‘control’ being important. As a writer, producer and director, as well as an actor, Ekman had considerable control, as shall be seen later. On the other hand, it is hard to judge how much control each individual has had on a film set without actually having been there to observe. That is why it is important to stress that with the approach taken in this book, the study of a larger body of work is essential. If there are clear links between the films of a particular filmmaker this strongly suggests that the filmmaker had at least some measure of control over how they were made. It is argued here that whether the filmmaker in question worked as a contracted studio director or as an independent filmmaker is not what decides his or her status as auteur. It is the consistency and cohesiveness of their oeuvre that matters in this definition. This empirical approach to auteurism means that most, if not all, films of the individual filmmaker under investigation should be watched. Additionally, films made by many other filmmakers working at the same time, and before, should also be analysed in order to be able to pick out what it is that makes this particular body of work special, and to be able to see the unique contributions made by a particular auteur. This book further argues that there is a difference between ‘director’ and ‘auteur’ in the sense that ‘director’ is a job title, describing a person from the moment they start to work on the film set, whereas with the definition of an auteur used in this study it is not meaningful to say of a first-time director that s/he is an auteur. A larger body of work that can be analysed as a whole is needed.

Another difficult question, besides the cooperative aspects of filmmaking, and one which is perhaps an integral part of the discussion of authors and authorship, is the autobiographical aspect. Links between an artist’s work and his/her own personal life and history have been made repeatedly over the ages. It is common enough either to consciously look for the connections between a character (in a book or film) and the artist, or to compare specific events or actions in the artist’s past with specific events or actions in the artwork. However, one potential problem with looking for such links is the autobiographical fallacy. Any work of fiction, regardless of how closely linked it may appear to be to the artist’s life, is still a processed story, where things have been altered and manipulated. Sometimes this is done simply to better fit the narrative structure and sometimes it is done in a deliberate effort to change the reader’s or viewer’s perception of what really happened. The artist might, for example, overplay dramatic events in order to evoke sympathy or give a narrative a happy ending which in real life ended tragically. What the artist says about his/her work may also be part of that process of alteration and manipulation. A correlation between a character in a film and the actual filmmaker does not necessarily mean they are the same person. However, it is not the case that autobiographical readings should be dismissed out of hand. It is close to impossible to create a narrative without using, consciously or unconsciously, real-life experiences and putting them into the story, the structure. Here it is also important to consider the fact that even if an artist vehemently denies that there is anything autobiographical in their work, that should not be taken at face value either. They may not want to admit it, or may fail to see it, even though the biographical aspects might still be there, and obvious for someone else. While acknowledging these concerns, in this book there will be autobiographical readings of some of Ekman’s films. (For discussions on autobiographical readings, see Mazierska & Rascaroli (2004) or Staiger (2008).)

The history of film is filled with auteurs and to make the discussion more precise, distinctions between different kinds of auteurs are helpful. I would like to propose a new one, the distinction between external auteurs and internal auteurs. An external auteur would be somebody who simply makes films yet has no presence in them, even though the films have thematic and stylistic consistencies and recurring motifs. An internal auteur would be somebody who, besides making the films, has a strong presence in them, either personally and/or through a voice-over and/or by including strong autobiographical elements in the film. External auteurs are more common, for instance Henry Hathaway or Gillian Armstrong. Internal auteurs are not as common, but among the more prominent in narrative cinema are Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Federico Fellini, Chantal Akerman, Clint Eastwood, Orson Welles, François Truffaut, Woody A...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. On Auteurs and National Cinema

- 2. The Social Context

- 3. Swedish Cinema

- 4. Hasse Ekman in the Renaissance

- 5. The Early 1950s

- 6. The Final Years

- 7. Ideas and Legacy

- Conclusion

- Filmography

- List of Works Cited

- Index