![]()

1

“Minty” Ross, Her Family, and Slave Life in Antebellum Maryland

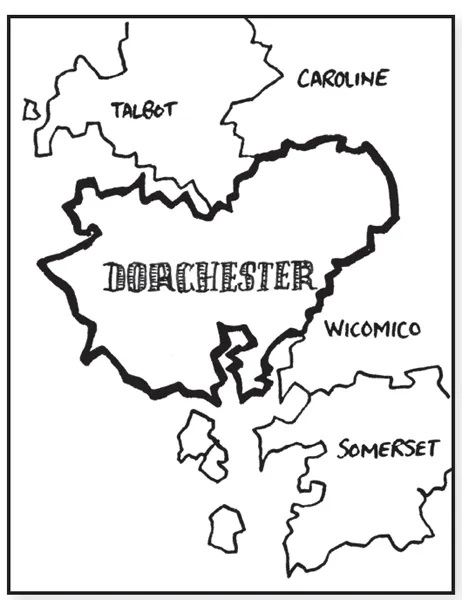

IN 2005, TWO GREAT-GRANDNIECES OF HARRIET TUBMAN had an opportunity to travel to Ghana, West Africa, where they believe the seed of their genealogy in America was sown. Here they would complete the circle that started in the early to mid-1700s when Modesty, an Ashanti girl, was ripped from her tribe in or near Accra, Ghana, and brought to the American colonies. She was eventually purchased by Atthow Pattison, a successful landowner and slaveholder in southeast Maryland's Dorchester County. Records indicate that Modesty was the mother of Harriet “Rit” Green, who would become the mother of Harriet Tubman.

Geography is always important in understanding the course of history and, in this case, the struggles that precipitated the decisions made by the enslaved and slave owners. Here the setting is southeastern Maryland and the land settled and owned by white slaveholding families. Maryland's proximity to the North—the Mason-Dixon Line formed its border with Pennsylvania beginning in the 1760s—made the structure of slavery in that colony different from most others, particularly those farther south that relied on labor-intensive cotton.

Landowners in the Dorchester region appeared to have a simple formula for growth that turned into an unwritten rule: marry within the area to amass wealth. As a way of increasing their property holdings and status, white landed gentry would intermarry with other estate owners in the region. Over the generations, the leading families on Maryland's Eastern Shore consolidated control over vast expanses of rich farmland, forests, and marsh areas.

Harriet's family from the time of Modesty was intricately involved with four white families in the Dorchester region: the Pattisons, the Thompsons, the Brodesses, and the Stewarts. As the landed white families merged, shifted, and expanded their estates, African American slave families were moved around the regional network. By the 19th century, black family units were interwoven among Dorchester's landed white families, creating a large network of interaction and communication throughout the area. Enslaved blacks often worked alongside free black men at the docks or in skilled labor markets, sharing information and extending the network over time.

The interrelations among blacks and white, and the relationships among the area's white families, created the setting and cast of characters for the drama that was to come.

Pattisons and Brodesses

In 1776, the year the Continental Congress signed the Declaration of Independence less than 150 miles to the north, Atthow Pattison's 265-acre estate in Dorchester County included five slaves. Modesty, the grandmother of Harriet Tubman, is believed to be one of them. By 1790 the number enslaved had increased to seven; Rit, Tubman's mother, was born into the household sometime between 1785 and 1789. Upon Pattison's death in 1797, ownership of Rit passed to his granddaughter, Mary Pattison. Three years later, Mary went on to marry Joseph Brodess, a local farmer in the central Dorchester town of Bucktown. On June 14, 1801, Mary gave birth to Edward Brodess; a little more than a year later, Joseph Brodess died.

The Thompsons

Anthony Thompson was a moderately successful and respected businessman and landowner whose family lineage went back to the founders of Dorchester County. He considered himself a benevolent caretaker because of his promise of manumission for the loyalty and good behavior of those he held in bondage. His wife, Polly King, died between 1800 and 1803, leaving him with three sons under the age of 15—Edward, Anthony, and Absalom. Thompson owned nine slaves; one of them was Ben Ross, who was to become the father of Harriet Tubman.

In keeping with the unwritten formula for regional expansion, the recently widowed Anthony Thompson and the recently widowed Mary Brodess married in 1803 and consolidated their assets. Mary Brodess brought her son, Edward, and her personal slave, Rit, along with four enslaved males that had belonged to her deceased husband.

The Stewarts

The Stewarts appeared to be a family of mixed ideals. Joseph Stewart, Anthony Thompson, and Robert Tubman were among the county commissioners who oversaw the operations of the Black Water and Parsons Creek Canal Company, set up to expand the shipment of goods across the area's extensive waterways. The project was completed in the 1830s after twenty years of effort and named the Stewart Canal. Joseph's son, James A. Stewart, was the Pattison family attorney, a businessman, and later a US congressman. He was a major slaveholder and is not recorded as having manumitted any of them. (His brother, John T. Stewart, later hired a teenaged Harriet Tubman.) Joseph's brother Levin, however, went to court and turned in documents to manumit all of his enslaved at specified ages. Levin's friend James Pattison did the same a year later. These and other manumissions during the 1850s helped develop a free black community in Dorchester County.

To be clear, Levin's actions were hardly the norm. Even though he had less need for slaves than area farmers because he was going into the shipbuilding and trading business with his brother in Georgetown, he could have sold his slaves for top dollar to a Baltimore or New Orleans trader. Instead, he sold or gave them to his brothers, who honored the manumission schedules after his death in 1825.

Masters and the Enslaved

The master-slave relationship may have seemed complicated on one level, but it was quite simple on another.

While it appears that a few slave owners were moved by the soaring sermons of Quakers and preachers to appease their consciences by promising manumission to their human chattel, more were motivated to do so by the shifting tide from agriculture to industry on the Eastern Shore. Most, however, kept their enslaved despite declining need. Owners often found they could make more money on a slave by hiring him or her out to local farmers and businessmen than they could by selling them to a New Orleans or Mississippi slave trader. It also paid for slave owners to create incentives for their African forced laborers to remain loyal and dependent, thereby avoiding the cost and aggravation of tracking runaways or losing their property altogether.

Still, the enslaved in the Chesapeake region faced the constant threat of being sold into the Deep South and losing contact with family members forever. The threat of permanent, distant separation was especially acute wherever a slave owner's business was not thriving. Black families were considered fortunate if their loved ones were sold or transferred by marriage or inheritance to another white owner in the region. Only the lucky were granted the privilege of hiring themselves out by their owners, typically for an annual fee. This gave enslaved men and women the opportunity to “moonlight” and, over time, buy their own freedom.

When it came to buying one's freedom, however, time was a major obstacle. If a black man managed to buy his own freedom over a period of years—which it often took—he might not have time to buy freedom for his wife and children before they were sold on the auction block. The same held true for a free black man who married an enslaved woman. The children of the marriage took on the status of the mother rather than that of the father. And so, even when freedom was a real possibility for the African American man, he did not control the fate of his wife or children. The slave owner could decide to sell them or keep them at any time. How free was a man if someone else could determine the destiny of his loved ones?

Slavery may not have seemed as harsh in Maryland as it was in other parts of the country—especially where cotton was king—but it was still a living hell, with the constant threat of being dragged deeper into the pit of the South. Less complicated than all the conditions and limitations of manumission was the simple fact that a slave owner did whatever he deemed in his own best interest and that of his family, rather than that of the enslaved and enslaved family.

And yet, while hiring out their human property seemed advantageous for Maryland slaveholders at the time, they did not take full account of the connections developing among the region's farms and other workplaces. A growing network of free blacks, hired enslaved, and mariners along the Eastern Shore was forming in preparation for the escapes that were to take place just as Harriet Tubman was coming into the world.

Harriet is Born

Ben Ross was skilled in lumber inspection and managed the timber operations of the Thompson estate. He was one of only a few of Thompson's forty slaves who was promised land upon his manumission at age 45.

When Mary Brodess inherited Harriet “Rit” Green from her grandfather, Atthow Pattison, in 1797, the terms of his will stipulated that his slave wo...