![]()

PART 1

THE GUTS OF A GREAT PROJECT MANAGER

By guts, I mean grace under pressure.

—Ernest Hemingway

If PMs listened to their gut instincts a little more (“We missed our dates the last three times out—what makes us think we’ll make the date we estimated this time?”) and paid a little less attention to the tools and rules and software and mechanics, we’d all be better off. And if you’re that guy who insists that the first thing your new project management office needs to do is a thorough evaluation of PM software alternatives, you’re not helping at all. Tools and rules and software and mechanics are fine in their place, but only if and after they’re informed by practical, I-know-in-my-guts-that-this-is-true PM thinking—the kind of thinking that the best PMs exhibit regardless of the kind of project they’re on, regardless of the tools and rules and software they’ve got.

And that’s what Part 1 of this book is about: the kind of thinking that speaks directly to the good gut instincts of PMs. The next two parts after that will add on the practical how tos: how to apply good project management thinking in planning (the hard part), and then how to manage the project day to day (the easy part, if you do the planning right). But for now, we’re talking about the guts-aware thinking that forms the mental framework for effective PMs: the mindset that allows them to connect all the pieces, to see and act on the linkages between risk and uncertainty and the schedule, between the project’s stakeholders and its critical deliverables, between its measures of progress and its ultimate project performance, between its priorities and how project changes are handled in light of those priorities. Here’s what’s in the guts and brains of the best PMs.

![]()

CHAPTER 1

A WILLINGNESS TO LEARN FROM THE PAST

It’s what you learn after you know it all that counts.

—Harry S. Truman

The best PMs are always thinking about what’s in front of them in the context of what they’ve learned from the past. And if that past wasn’t always great, they won’t blindly, irrationally assume that things will be better this time, especially when there’s no evidence to support that optimism. Even if (maybe especially if) they hear, “It’s different this time, really.” Here’s what they know: Without a change in thinking and approach, no, it isn’t.

It’s the first question I ask when I’m interviewing PMs: What did you learn from your last project experience? And it’s a bad sign if they take a long time answering.

The best PMs are always asking: What have we learned here? And how can we apply what we’ve learned going forward? More specifically, what have we learned that’ll allow us to:

- Repeat the good outcomes, and

- Make sure we don’t make the same mistakes again?

It’s a key question to ask about any PM or organization that works on projects: has he, she, or it ever made the same project mistakes more than once? If so, they’re not learning—not learning about the critical importance of comprehensive project closeout reports (see Chapter 16) or about the importance of planning for and tracking mandatory performance deliverables (see Chapter 9), for example. The best PMs institutionalize learning; they won’t compromise on the need to do project closeout reports on every project, and you’ll see them run reviews at the end of every phase of a project to ensure their team gets better, every step of the way.

![]()

CHAPTER 2

A NEED TO KNOW WHY

When dealing with people, remember you are not dealing with creatures of logic, but with creatures of emotion, creatures bristling with prejudice and motivated by pride and vanity.

—Dale Carnegie

As far as I can tell, there are two inviolable truths about people and projects:

- There’s a reason behind everything that everyone does on, to, for, with, or against a project. No one does anything without a reason.

- In a stakeholder’s mind, no matter what they are doing on, to, for, with, or against a project, it makes complete sense to them.

The key skill for a PM then, is figuring out: where are these project stakeholders coming from, and most important, why are they acting the way they are? (“Because he’s an idiot!” is never the right answer.) The thinking PM asks “Why?” all the time, guided by two principles:

- He never allows himself to think that someone is doing something “just because he’s stupid.”

- He never treats anyone as an “enemy” of the project but, rather, as a potential ally he just hasn’t figured out yet.

This approach makes a broad assumption about the intent of the project stakeholder community: It’s very rare that a stakeholder is really out to kill a project, even if it feels that way sometimes.

Asking “Why?”—over and over and over again—should take the PM back to root causes. Without an understanding of the root causes of a stakeholder’s behavior and their attitude toward a project, the PM probably won’t be able to put an effective stakeholder management plan in place.

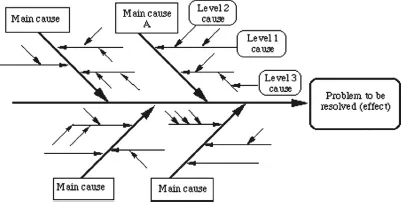

Getting to Root Causes: The Fishbone Diagram

The fishbone diagram, also known as an Ishikawa diagram or a cause-and-effect diagram, came out of the Japanese quality management push in the 1960s. Although it’s more often used to analyze the root cause of product defects, it’s also very helpful to PMs in understanding their stakeholders.

Wikipedia offers this example of root cause thinking1:

“My car won’t start”.

“Why?”

“Because the battery’s dead.”

“Why?”

“Because the alternator isn’t working.”

“Why?”

“Because the alternator belt is broken.”

“Why?”

“Because the belt was well beyond its service life—it’s never been replaced.”

“Why?”

“Because I guess I haven’t been maintaining my car according to the recommended service schedule.”

And that’s the root cause (although you could keep going to figure out why he isn’t maintaining his car, but you get the idea). So how would a root-cause analysis work with a difficult project stakeholder?

Project Business Lead (PBL): “We’ve invited Bob Miller to the inventory management process redesign sessions a number of times, but he just isn’t attending, and that’s a problem—Bob’s got a lot of influence with the VP of manufacturing.”

PM: “Why do we think Bob’s not participating?”

PBL: “He says that the way we’re tackling process optimization is stupid.”

PM: “Stupid how?”

PBL: “He says that we haven’t fully considered how things work in his plant.”

PM: “Why does he think that?”

PBL: “Because we don’t have his warehouse manager on the inventory management redesign team.”

PM: “Why not?”

PBL: “Because the COO—our sponsor—chose a warehouse manager from another plant.”

PM: “So?”

PBL: “So Bob’s warehouse manager had put his name in the hat for that role on the team.”

PM: “And …?”

PBL: “And Bob and his guys are convinced that the next set of promotions will only go to people who are on the project team.”

Now we’re getting somewhere. Now we’re at the root cause, and we have information the PM can act on—something he can take up with the sponsor.

Note

![]()

CHAPTER 3

A WILLINGNESS TO ASK FOR HELP

He who is afraid of asking is ashamed of learning.

—Danish proverb

The best PMs are always asking for help. It’s not because they don’t know the answers, and it’s not because they don’t want to do things for themselves. It’s because they understand the power in asking questions, and they know that people—sponsors, team members, stakeholders—like to be asked to help and very rarely, if ever, say no when they’re asked.

Asking for help says to the people you’re asking that you respect their views and that they have a role in the project and a view that’s worthy of your consideration. It gives you a chance to voluntarily take yourself off your PM pedestal (if you were ever on one) instead of being knocked off it, and it establishes a collegial relationship with the person you’re asking. It’s just a good approach in general. Don’t ask questions, of course, if you have no intention of listening or responding to what you’re hearing; people will see through that kind of disingenuous approach.

PMs should know that they need everyone’s help and that if they’re not asking, they’re missing something. Which is why a common complaint of project managers—“As PM, I have all the responsibility to get things done, but none of the authority”—is, I think, somewhat misdirected. That kind of thinking displays a fundamental misunderstanding of the role of the PM. The best PMs don’t have all the responsibility for project outcomes—rather, they share it effectively with people like the sponsor—nor do they really require all the authority to be successful. The best PMs—and this is probably true of all effective leaders—rarely exercise their positional power even if they can do so easily. Instead, they lead by influence and, certainly, by the will of those they’re leading. They ask for help a lot.

Making It Their Solution: Leading Others to the Answer You’re Looking For

Watch the most successful negotiators (and good PMs are nothing if not successful negotiators), and you’ll see that they’re really good at leading people to solutions that are in their own best interest while making it look as if the solution was the other person’s idea all along. Good negotiators make it easy for others to come to a conclusion the negotiator’s already reached. “I need your help,” they’ll say. “Here’s what I’m seeing. What are you seeing? What do you think we should do here?”

If you really do have a solid solution or answer in mind that makes sense objectively and that you can lay out in organized fashion, you can reasonably expect the person you’re asking for help will come to the same conclusion. The difference, of course, is that the other person will think that the conclusion was their idea, and their buy-in will then be that much stronger. It doesn’t really matter whose answer it is, as long as it’s workable; if it comes from one of your important project stakeholders, all the better. It’s a subtle art—just don’t be too obvious about what you’re doing; people will see through you right away if you are. And remember that this approach doesn’t work if you’ve got a really bad idea that you’re just trying to jam down someone else’s throat. A bad idea, or even a good idea lacking a logical presentation, just won’t fly, no matter who owns it.

![]()

CHAPTER 4

TAKING DEAD AIM AT OUTRAGEOUS OPTIMISM

We descend into hell one step at a time.

—Charles Baudelaire

In project management, unwarranted optimism is a dangerous thing. Watch out when you hear: “How do you know it can’t be done that fast?” or “It’s different this time” or “You need to be more of an optimist!” These statements imply that the speaker hasn’t looked at the historical evidence—or that there is no historical evidence. They’re an attempt to appeal to the emotions, with a bit of baseless cheerleading thrown in. Any one of these statements is frustrating; in combination, they’re deadly. Fortunately, there are ways to fight back.

Look at What Happened in the Past

We know that some projects, given their schedule, cost, and performance constraints, are headed for the tank right from the beginning, but we just can’t...