![]()

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

GENERATIONAL STUDIES

The notion of generation as a construct of investigation can be traced to Karl Mannheim’s (1952) seminal work, “The Problem of Generations.” In his essay, Mannheim describes a generation as individuals “who share the same year of birth, are endowed, to that extent, with a common location in the historical dimension of the social process.” However, he notes that simply sharing the same location (i.e., born at the same time) is not sufficient since individuals must also experience the same events. Mannheim adds that a generation must be an actuality, whereby members of the same generation are exposed to and participate as a social unit within a historical period. As a social unit, these individuals undergo a pattern of events, although interpreted differently, and form an identity shaped by their common experiences. His influential work has spawned a body of literature in sociology, anthropology, demography, psychology and, more recently, management and organizational studies.

Following Mannheim’s work, Strauss and Howe (1991) later wrote about American history, which is articulated from the lens of generational biographies. They suggest that generations are a recurring cycle of 20 years. Similarly, Strauss and Howe go on to explain that each generation share a common location in history, have beliefs and behaviors that are shaped by key defining events, and they (members of a generation) identify with their peers from the same generation. Their writing gained widespread attention and popularity. They followed up with other titles, 13thGen: Abort, Retry, Ignore, Fail? (1993), which focused on Gen X, and Millennials Rising: The Next Great Generation (2000), which focused on the Millennial generation.

The works of Mannheim as well as those of Strauss and Howe have generated an awareness that shifting demographics is accompanied by a shift in employee attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors in the workplace. Other books on generations also begin to emerge. In Canada, Foot and Stoffman (1996) wrote about how to profit from demographic shifts in their book, Boom, Bust and Echo. They claim that demography explains two-thirds of everything, from real-estate meltdowns to the changing nature of work. Foot and Stoffman also conjecture that changing demography is a useful tool for forecasting the supply and demand of goods and services and consequently labor; it is useful for employers, corporations, and government.

Barnard, Cosgrave, and Welsh (1998) further wrote about how to market, employ, and engage with Gen X, in Chips & Pop: Decoding the Nexus Generation. The book centers on Gen Xers and how to reach out to a challenging (following Douglas Coupland’s characterization of Gen Xers as a dissatisfied and disenchanted) generation as consumers, employees, and citizens. As the Millennials begin to show up in classrooms and the workplace, Jean Twenge (2006) followed up with the youngest generation (at that time) with Generation Me. In her book, Twenge seeks to explain why present-day youths are more confident, assertive, and entitled than previous generations. Her book resonated with a lot of parents, teachers, counselors, and employers, which led to a burgeoning consulting industry that is focused on working with and managing the Millennials.

Other authors focused on managing generational differences, more specifically in the workplace. Zemke, Raines, and Filipczak (1999) wrote about the four generations in the workplace, namely, Veterans, Boomers, Gen Xers, and Millennials, highlighting generational differences and offering advice on how to manage them. Likewise, Lancaster and Stillman (2002), using slightly different terms for the generations (e.g., “Traditionalists” in place of “Veterans”) also described the four generations that are currently coexisting in the workplace, their differences, and how to bridge the generational divide. Suffice to say, these books are rooted in Canada and the United States with little attention paid to generational work in other countries. To fill this gap, we edited a volume Managing the New Workforce: International Perspectives on the Millennial Generation, to document studies of the Millennial generation as a primary focus, across 23 different countries including Australia, Canada, China, Europe, and South Africa.

GENERATIONS IN THE WORKPLACE

The four generations frequently reported in the research literature and popular press are Veterans, Baby Boomers, Generation X (Gen Xers), and Generation Y (Gen Y or Millennials). Some authors have used slightly different terminologies to describe them, notably referring to the Veterans as the “Silent Generation” or “Traditionalists” (see Lancaster & Stillman, 2002; Strauss & Howe, 1991). Foot and Stoffman (1996) also used “Baby Bust” (1967–1979) to refer to Gen Xers, and “Baby Boom Echo” (1980–1995) to refer to the Millennials. Given the focus of our research in Canada, we have adopted “Matures” (in place of Veterans), “Baby Boomers,” “Gen Xers,” and “Millennials” in keeping with the terminologies that are commonly used in both the research literature and popular press.

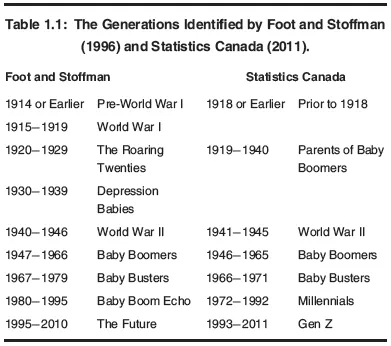

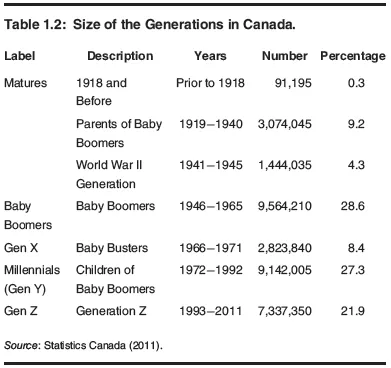

Foot and Stoffman (1996) and Statistics Canada (2011) employ similar cutoff years to identify the various generations in Canada. Statistics Canada defines a generation as “a sudden rise in the births observed from year to year, […] [and] ends with a sudden drop in the number of births […].” Likewise, Foot and Stoffman describe a generation as “sustained high numbers of births.” A comparison between Foot and Stoffman’s and Statistic Canada’s generational cohorts is provided in Table 1.1. Table 1.2 also provides the size of the various generations in Canada.

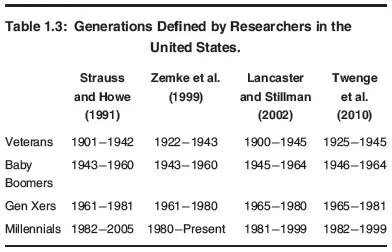

We note that these cutoff years differ from research conducted in the United States (e.g., Lancaster & Stillman, 2002; Strauss & Howe, 1991; Twenge, Campbell, Hoffman, & Lance, 2010; Zemke et al., 1999). See Table 1.3 for cutoff years used by researchers in the United States. In reality, the exact years demarcating a generation matters less than the shared experiences and historical events that shape their worldviews, values, beliefs and attitudes. For example, we will not anticipate someone born in 1980 (a Millennial) in Canada (or a Gen Xer) to differ in substantive ways, given the historical and geographical proximity to each other.

In this book, we will primarily focus on the four generations, namely the Matures (born before 1945), Baby Boomers (1946–1964), Gen Xers (1965–1979), and Millennials (1980–1992), since they not only constitute the largest generations, but are also found in the workforce during our research period. We also use the cutoff years specific to Canada based on Statistics Canada’s definition of a sudden rise (or fall) in birth rates from year to year. Each of the generations is briefly described below.

Matures (Before 1945)

Although the Matures generation span pre-World War I to the World War II, we are primarily interested in those between 1941 and 1945 as they are still in the workforce when our project commenced. Matures entered the workforce following the war, and were part of a prolonged period of economic growth fueled by demands generated by the Baby Boomers (see Foot & Stoffman, 1996). As a result, we anticipate they would follow a traditional or linear career pattern, one that is characterized by steady promotions, few employer changes, and long-term employment.

Baby Boomers (1946–1964)

The Baby Boom generation, which lasted for 20 years, forms the largest workforce at the time of our research. As the largest cohort, they drove up demands, powered the economic engine (post-war growth), and set the trends (Foot & Stoffman, 1996). When the Boomers entered the workforce, unemployment rate was low, and they generally experienced linear, upwardly mobile careers. The Boomers also saw an increasing number of women entering the workforce. As a result, many workplace practices such as gender equality, work/life balance, and family friendly policies were introduced. Given the long periods in which Boomers remained in the workforce, coupled with economic cycles and changing nature of work, some would change jobs, employers, and even career tracks. We anticipate Baby Boomers will experience some lateral and even downward movements, as employers would down size or reorganize themselves.

Gen Xers (1965–1979)

Following the Baby Boom generation is a smaller cohort that was often portrayed as less successful compared to the Matures and Boomers. This generation, popularly labeled “Gen Xers,” is aptly characterized in Douglas Coupland’s novel, Generation X. As a generation, they faced a poor labor market when they entered the workforce (Statistics Canada, 2011). When the economy improved, they were too old for entry-level positions and lacked experience for more senior roles (Foot & Stoffman, 1996). As a result, many had a delayed start in their careers. Many Gen Xers are said to live in their parents’ basement when they were in their thirties. We anticipate Gen Xers will have greater job and career movements, as they find their place in the labor market. This also reflects the demographic bind Gen Xers find themselves in, as they arrive behind a large cohort (i.e., Baby Boomers) who still occupies key positions in organizations and the industry.

Millennials (1980–1992)

Millennials are the children of Baby Boomers, and as a result, they are very much influenced by their parents. As the Boomers have done well for themselves, the Millennials are raised in a relatively middle-class environment (Foot & Stoffman, 1996). They have high post-secondary participation rate, experience rapid technological changes, and saw the same number of males and females entering the labor force (Statistics Canada, 2011). Millennials also enter a tumultuous labor market with the global financial crisis (beginning in 2007–2008). The changing nature of work, driven in large part by technological advancement, saw jobs changing or disappearing alongside the emergence of a “gig economy,” which is characterized by part-time, short-term, lower paying jobs. On this basis, we anticipate Millennials will experience the greatest job, employer, and career track changes.

Based on the foregoing, we surmise that each generation, based on their cohort size, having been exposed to significant historical events – such as an economic boom or crisis, technological advances, globalization, and mass migration – will display different work values, hold different attitudes toward work, and form different expectations about their careers leading to different career trajectories.

GENERATION – FACT OR ARTIFACT?

A major criticism of generational research is the lack of empirical evidence to substantiate claims of generational differences. Some studies found that the effect sizes were small (e.g., Becton, Walker, & Jones-Farmer, 2014) or the differences are not meaningful (Costanza, Badger, Fraser, Severt, & Gade, 2012), leading some researchers and commentators to call generational differences a myth (Costanza & Finkelstein, 2015). For example, a study conducted in Australia examining personality and motivations found no difference across Baby Boomers, Gen Xers, and Millennials (Wong, Gardiner, Lang, & Coulon, 2008). In reality, most research on generational differences is cross-sectional in nature, often resulting in an inability for these studies to distinguish between the effect of maturation and true generational differences. Second, the four generations conceptualized above are based on sociohistorical events that occurred in the West (usually the United States), and thus may not be valid for samples outside of the United States. Many researchers conducting studies outside the United States erroneously adopt the same birth years or cohorts without considering the national contexts in which they study. For example, Egri and Ralston (2004) found that the value orientations between U.S. and Chinese workers differ significantly within the same generation due to national and cultural differences. Third, many generational studies fail to consider the heterogeneity that exist within a generation. For example, in an era that is characterized by globalization and greater worker mobility, younger generations are much more likely to be heterogeneous in terms of gender, race (including ethnocultural diversity), and urban/rural socializing and outlooks, leading to a diversity of identities that are adopted by a single generation (see Lyons, Ng, & Schweitzer, 2014).

Furthermore, in demography studies, researchers frequently use birth years to demarcate a generation, rather than relying on social, economic, or political factors (Statistics Canada, 2011). This is problematic since a study cannot meaningfully detect differences across generations are produced by maturity or life stage. For example, we found that many research models detect no generational differences after controlling for age.

It is important to emphasize that a generation, as conceptualized by Mannheim, shares a social space, experiences a common set of events, and has a uniform reaction to (or identifies with) those events, rather than birth years alone. Joshi, Dencker, Franz, and Martocchio (2010) propose another conceptualization of generation as an identity, in which individuals self-identify as belonging to a cohort. In this regard, Urick, Hollensbe, Masterson, and Lyons (2016) have found support on identity-based generations, which can give rise to intergenerational conflicts.

Thus, in order to detect generational differences from life stage effects, we need to clearly distinguish between age effects, period effects, and cohort effects.

Age Effect

Following Parry and Urwin (2011), age effect occurs as a part of human maturation, in that regardless of the generation to which one belongs or identifies with, they will behave in the same way as those who preceded them during the same life stage. For example, someone is more likely to be engaged in career exploration in their twenties, establish and advance in their careers between their thirties and fifties, and maintain or wind down their career as they approach their fifties and sixties. As such, individuals who are in their twenties, regardless of generations, are more like each other, than with they are like themselves as they age.

Period Effect

Period effect refers to historical events or activities that led to a certain generation to form certain values, attitudes, and behave in certain ways. For example, the great depression and the world wars have shaped the values and attitudes of the Mature and Baby Boom generations with respect to work and responsibilities.

Cohort Effect

Finally, cohort (or generational) effect represents the effect that represents differences that is detected when we compare one generation to another. Thus, the shared identities and common experiences that result from exposure to a set of historical events (e.g., period effect) would set one cohort apart from another, thus allowing us to find differences in values, attitudes, and beliefs across different generations.

...