![]()

Chapter I

Introduction

David Peacock and Lucy Blue

Since Eritrea gained its independence in 1993, very little archaeological work has been possible as the country was rebuilding itself after 30 years of war with Ethiopia. The scars of this war remain and present a considerable hazard to field work, in the form of minefields and unexploded ordnance, as we were to discover. After a preliminary visit in 2002 and more extensive discussions in Asmara in 2003, we were able to launch the Adulis project in 2004, although by 2006 tightening government regulations made continuation impracticable. The project was conceived as a non destructive survey without recourse to excavation. The latter seemed premature in the current state of Eritrean archaeology, where even a basic topographic map of the site and its surroundings was lacking.

The Environment

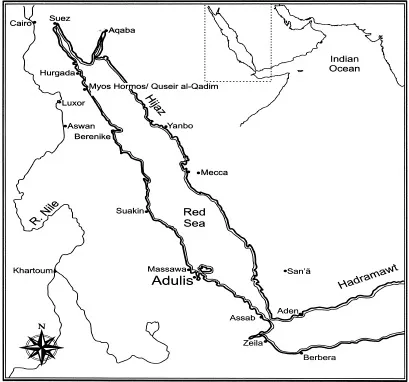

Adulis is situated on the Bay of Zula on the western shore of the southern Red Sea (Fig. 1.1). It comprises a series of low mounds covering an area of nearly 40 hectares, now partly covered with low scrub (Fig. 1.2). The bedrock here is a fine yellowish alluvium, but volcanic rocks are found near Foro and in the Galala Hills. To the north is the metamorphic Ghedem massif, which dominates the site and in the rainy season often capped with cloud. This is almost certainly the Montuosa Chersonesus of Claudius Ptolemy (Geog.Book 4, chapter7; Stevenson 1932).

From June to September it becomes very hot (40-50° C). In the period December to February (rainy season) the temperature varies from 20 to 35° with an average annual temperature of 30° C and an annual precipitation of about 200 mm. Around Adulis are fields, which are farmed by the inhabitants of the neighbouring villages of Zula and Afta, although many of these are barren perhaps because of climate change. The main economy seems to be based on the herding of sheep, goats and camels, with relatively little exploitation of marine resources. The coastal strip is also home to local Rashaida nomads, whose tents are usually in evidence. The local fauna is rich and varied with significant numbers of gazelle and ostriches.

At the entrance to the Bay of Zula is the hilly island of Dese, which contrasts with the flat Dhalak islands further to the north-east (Fig. 1.3). The waters in this area are easily navigable and generally much more sheltered than the northern Red Sea which is dominated by northerly winds for much of the year. Massawa, 50 km to the north of Adulis, is the main port of Eritrea and capable of accommodating sizable vessels. The sea abounds in fish, no doubt attracted by the coral reef.

Figure 1.1 Map of the Red Sea area showing the location of Adulis

Adulis in Antiquity

The port of Adulis was one of greatest significance in Antiquity. It is best known for its role in Aksumite trade during the 4th-7th centuries AD. It is connected to Aksum in Ethiopia by a tortuous mountain route to Qohaito, thence across the plateau to the city itself. However, it is also a major port of the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, a sailors’ hand-book of the mid 1st century AD, concerned with the journey between Egypt and India (Casson 1989). We learn that, not only did Adulis offer a good harbour on the route to India, but it was also a source for luxuries such as ivory, tortoise-shell and rhinoceros horn. Whilst the equation of the site with the historically attested town of Adulis is broadly acceptable, from the outset it appeared that there were a number of chronological and topographical issues which could be economically addressed by field survey. Firstly, the surface pottery appeared to be late in date, according with the Aksumitic importance of the town. There must however, have been earlier activity on the site, because of its mention in the Periplus and because pre-Aksumitic pottery from this region has been found at Quseir (Myos Hormos), in Egypt, in 1st century contexts (Tomber 2005b). Paribeni (1907) conducted excavations at the beginning of the 20th century which revealed two phases of occupation: a later Aksumite and an archaic phase, which it seemed dated many centuries earlier. It was felt that careful, gridded study of the surface pottery might well reveal that parts of the site were occupied at the earlier and perhaps Roman date.

Figure 1.2 A view of Adulis showing the typical topography with scrub covered mounds

In addition, there were significant topographic problems. Adulis is referred to as a port, yet it now stands some 7 km from the sea. At the time of the Periplus it was 20 stades (3.3 km) from the coast. It is therefore clear that there has been major coastal change in the area, which at present remains relatively poorly understood. The site does appear to have been connected to the sea by a silted river channel, and if this was active in the Roman and Aksumite periods then Adulis may have been a fluvial rather than a maritime port. The Periplus itself refers to ships mooring near an island approached by a causeway, for which there is no evidence at Adulis. Theories have thus evolved that suggest that the site was originally at Massawa, 60 km to the north, which today comprises islands connected by causeways (Casson 1981), though it is equally plausible that an island and causeway, now obscured by coastal change once existed much closer to the site of Adulis. These questions could only be answered through a detailed analysis of the maritime environment on the plain of Zula.

Figure 1.3 The maritime approaches to Adulis

The work of Cosmas Indicopleustes, ‘Christian Topography’, written in the 6th century AD provides us with an introduction to the town in the Aksumite period. It contains a sketch map showing Adulis a little way from the coast, clearly connected with Aksum (Wolska-Conus 1968; here Fig. 2.1). It seems to have been an important place with a throne and inscription which Cosmas recorded. On the shore are two other places Gabaza and Samidi, which have never been identified. However, 3.5 km to the south-east are some low hills in a region now known as Galala, at the foot of which large quantities of 6th century pottery have been noted. It was suggested by Sundström (1907) that this could be the site of Aksumite Gabaza, the port of Adulis in this period. If this were indeed the case then it may also have been the location of the port in the earlier, Roman period.

The present project

It was felt that the problems outlined above were crucial to understanding this important site, and they could be answered simply and cost effectively by field survey. The work was therefore designed to comprise the following elements:

- topographic survey with a total station, recording the mounds and structures within them,

- geophysical survey using a fluxgate gradiometer (as the ground is too dry for effective resistivity) to investigate sub-surface structures,

- study of the surface pottery through systematic collection,

- study of decorative stones in the same manner,

- regional survey and geomorphological evaluation of the sedimentary strip between the site and the sea, involving coring the sediments,

- a coastal study of the area from Massawa to the Bay of Zula, including the island of Dese and the western coast of the Bure peninsula.

The following academic outcomes were anticipated:

- an assessment of the status and wealth of the town of Adulis,

- an insight into the urban layout of Adulis,

- an explanation of the whereabouts of Adulis of the Periplus,

- an enhanced knowledge of Aksumitic trade from surface evidence on its most important port,

- an understanding of the development of the harbour or rather harbours of Adulis.

As this report demonstrates all these objectives were achieved to some extent. This is, in itself, quite remarkable for it is seldom to match research design and outcomes in such an unambiguous way.

![]()

Chapter II

Historical background and previous investigations

Darren Glazier and David Peacock

Despite the prominence of Adulis in the antique world, surprisingly little is known of its origins. It is suggested by Huntingford (1980, 168-170) that the city may be equated with Strabo’s Saba and its elephant hunts, though this appears to be based upon little more than the absence of any mention of Adulis in Strabo’s account. The city does feature in Pliny’s Natural History, written c. AD 70, where it is described as a large trading centre for both the coastal and highland populations of the region (NH VI, 34) though it is unclear whether ‘large’ refers to the size of the settlement or the volume of trade. It is in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, however, that we find the first detailed description of the ancient settlement: the anonymous author of the Periplus, a remarkable sailor’s log of the mid 1st century AD, describes Adulis as ‘a fair sized village’ some twenty stades (3.3 km) from the sea (Casson 1989,53). The author suggests that ships with cargo bound for Adulis had previously moored at ‘Diodorus Island’, connected to the mainland by a causeway, but that attacks on the port installation from local barbaroi had forced ships to seek an alternative anchorage offshore at the island of ‘Oreinê’ (meaning ‘hilly’).

The Periplus refers to Adulis as ‘ a legally limited port’, though there has been considerable debate about what this means (e.g. Casson 1989, Appendix 1). Only three of the ports mentioned in the Periplus appear to be designated in this way, so trade could clearly take place elsewhere. It is suggested by Casson that the term indicates a market where trade was limited and controlled by a ruler, rather than a ‘free’ bazaar. In contrast, Huntingford (1980, 81) argues that the Periplus divides ports into four distinct types: appointed, or customary marts, established marts, legal marts and local marts. For Huntingford, Adulis belongs to the second category, meaning simply that it was recognised as the official market for the region. The Periplus is enigmatic, but our work in the region does suggest another alternative viz. that the phrase ‘legally limited port’ refers to a situation in which the port and market is separated from the town itself. This will be discussed in more detail in Chapter X. Whichever theory is accepted, however, it is clear that, by the middle of the 1st century, Adulis had become a thriving centre of international trade.

Adulis is described in the Periplus as ‘a fair sized village’, though most of the trade does seem to have taken place elsewhere, around the harbour itself. The Icthyaphagoi of the Dhalak Archipelago appear to have conducted a fairly substantial trade in tortoise shell through the market, whilst large quantities of cloth, fabric, brass, glass, copper and coinage and smaller quantities of wine, olive oil and jewellery were imported (Munro-Hay 1982). It is generally accepted that Adulis exported tortoise-shell, ivory, horn and obsidian (Munro-Hay 1982,109), whilst human trafficking in the form of slaves was substantial enough to be highlighted by Pliny (see Connah 1987, 72, 89 on slave trading in ancient East Africa). Wild animals for the Roman arena may also have attracted merchants to the region, as both elephants and rhinoceroses were found close to Adulis itself. It is interesting to note that no manufactured goods seem to have been exported from the region, whilst the imports consist mostly of luxury items for which there is unlikely to have been a mass market in the interior (Munro-Hay 1996, 405, 407). It is questionable therefore whether t...