![]()

CHAPTER 1

‘I’M AN AFME HUNTER PILOT...’

What a milestone! The point in 1968 at which I and my young colleagues were to be sent onward from advanced flying training to our operational conversion units (OCUs) was an unforgettable moment. We had undergone the rigours of initial officer training, enjoyed trying out our fledgling abilities on the Chipmunk and Jet Provost, and had marvelled that we’d mastered the slippery little Gnat. Now, the choice was essentially between Lightnings and Hunters. Those of us whose names came out of the hat for Hunters were thrilled to bits; not one who was headed for the day-fighter/ground-attack (DFGA) role doubted that we would have a marvellous time tearing around at low level and firing ordnance at ground targets. But it may surprise readers to learn that not all of our friends who were sent to Lightnings were quite as delighted. Of course there were some who had never aspired to fly anything else, and quite clearly the aircraft was an impressively exciting beast. But there was a perception amongst many that the air defence role was, despite the aircraft’s proclivity to catching fire and running out of fuel, somewhat boring. Most of us imagined that a Lightning pilot spent his time at high altitude, where there was no sensation of speed, flying on instruments and obeying the instructions of a ground controller. In our ignorance, we never considered the satisfying and demanding aspects of the flying, nor the opportunities for postings to Germany, Cyprus or Singapore. I certainly didn’t fancy the Lightning at the time.

Anyway, back when we youngsters arrived at 229 OCU at RAF Chivenor for our next course, all our preconceived prejudices seemed to be confirmed. For those of us headed for Hunters, the unit was an operational conversion unit pure and simple. We were taught all the various facets of the DFGA role: low-level navigation and attack; air-to ground weapons delivery of all types; air-to-air combat and gunnery; and so on. The pre-Buccaneer chaps (our Valley course was the first from which a couple of first-tourists were sent to the RAF’s latest jet) got all the low-level stuff but not the air-to-air, and seemed at the time to be generally content with that.

But the pre-Lightning boys appeared to receive the rough end of the stick. There was no low-level fun for them, and their course flying hours were made up with extra instrument practice and other beasts instrument practice and night flying. Neither did their night work seem terribly interesting; there was no attempt to introduce practice interceptions, so they simply bored holes in the sky on high-level navigation exercises. Tough luck, thought we DFGA types. We were enjoying ourselves, and that was all that mattered.

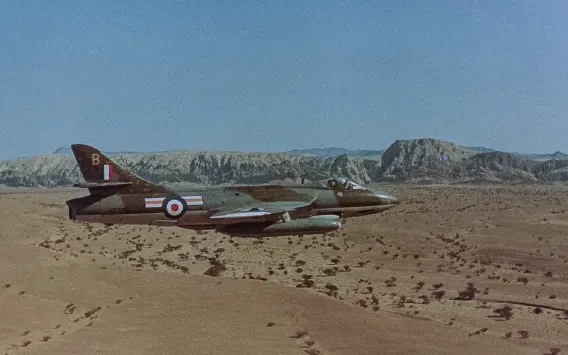

The 400-knot wash. A 208 Squadron Hunter releases its 100-gallon tanks at Rashid range, simulating a 50-foot level napalm delivery.

On completing the Hunter OCU I was thrilled to be posted to 208 Squadron at RAF Muharraq, Bahrain. But I still vividly recall my first meeting with my new squadron commander. I was wheeled into his office and saluted smartly. “I suppose I ought to say welcome,” said he, “but to be honest I’ve already got dozens like you and I could well do without another one. Anyway, just for the form, welcome.” A greeting never to be forgotten. I don’t recall him ever saying another word to me before he was posted away halfway through my tour.

He was right, though, about the vast numbers of first-tourists on his squadron, which had a somewhat unusual structure. The boss was a squadron leader – perhaps one of the last operational COs with that rank, for by that time most front-line units had wing commanders at the helm. The two flight commanders were flight lieutenants and they, together with a couple of QFIs (qualified flying instructors), an IRE (instrument rating examiner) and two PAIs (pilot attack instructors – that qualification soon to be renamed qualified weapons instructors, QWIs), formed the experienced cadre. The remainder of the total of twenty-two or so pilots were first-tour flying officers. This lack of balance led to the rest of the fighter force regarding the Bahrain Hunter squadrons as little more than advanced training units. That wasn’t altogether the case – as we shall shortly see – but there was nevertheless a grain of truth in the notion.

The structure was made even odder by the fact that, apart from the flight commanders and the QFIs, the rest of what might be described as the ‘top team’ were also of flying officer rank. Yes, the two PAIs and the IRE. This derived from the apparent view of those three gentlemen that ‘real’ pilots would rather not get promoted because of the risk of being sent to staff appointments; they simply wished to keep flying. They wore incredibly old and faded flying suits, adorned with the badges of squadrons on which they’d previously served. I guess this was designed to reinforce to us newcomers that they were terribly experienced operators, but it seemed a somewhat odd habit. Certainly, in later years, accepted practice was that one would only ever wear the badge of one’s current squadron; if anybody wished to display his previous flying history, then the wall of his den was the place.

Whether or not the pay rise which would have come on promotion to flight lieutenant was ever a factor I don’t know; perhaps it was negligible. But at any rate these characters wore their flying officer rank as something of a badge of honour to show that they hadn’t taken their ‘B’ exam. That routine test would have seen them automatically promoted to flight lieutenant and was, by the way, quite hard to fail.

Some time into my tour we got a new boss, and he decreed that all his flying officers must take the exam at the next annual sitting. Whether he had come under pressure from above or whether it was his own idea I’ve no idea – anyway, he insisted. Unfortunately, the exam that year was scheduled to be held at Muharraq slap bang in the middle of our annual live weapons (high-explosive, rather than inert) armament practice camp at Masirah. Now this wasn’t a major problem for all us young chaps – we were sorry to miss the APC, of course, but there would be others. But to dispatch the squadron on this important weapons event without its two specialist PAIs was a big call. Because I was in Bahrain taking my ‘B’ exam I have no first-hand knowledge of what actually happened down at Masirah, but the bush telegraph did bring word of a couple of incidents that might have been avoided if the experts had been running the show.

There is another story relating to those three senior flying officers and APCs. They were pretty good buddies as far as I knew, and were all good weaponeers; unsurprisingly, they were very competitive. During this particular APC one of them was scoring too well and, the story has it, his compatriots began to suspect that he must have been firing from closer than the minimum permitted range. They were unable to pin anything on him, because he seemed to be having consistently bad luck with his gunsight cameras; faults repeatedly caused his film to be unassessable. The other two had a good idea that those ‘faults’ were self-induced and, one day, arranged for his aircraft’s G90 camera to be loaded with film. This was a forward-facing camera mounted on the top of the aircraft’s nose; I don’t recall it being used at all during my time on the Hunter. Anyway, it required no additional cockpit switchery to make it function, so the man under suspicion would have had no idea that it was running during his next firing detail. Sure enough it confirmed the illegal parameters and our friend’s scores were instantly zeroed. He went pretty quiet for a while.

This chapter’s title stretches the truth, for I was not actually an ‘AFME’ Hunter pilot. AFME stood for ‘Air Forces Middle East’, the command organisation which had ruled RAF operations in the area until a couple of years before my arrival. The withdrawal from Aden had prompted reorganisation, following which squadrons operated under HQ British Forces Gulf. But the older hands on the squadron brought with them songs we used to perform in the bar late at night, amongst them the ditty whose first two lines went as follows:

We would happily roar away the evenings at Muharraq and Sharjah with a huge repertoire of similar classics, keeping ourselves endlessly amused. Although, I fear, probably not amusing the other residents of those messes.

There was a custom on Hunter squadrons that no two pilots could have the same first name. Therefore if a second Pete, for example, was posted in, he would be given an alternative name. ‘Sid’ was the favourite substitute, with ‘Bert’ following close behind. The problem would be compounded when these Sids and Berts were later posted to new squadrons, when it could quite easily turn out that a unit would finish up with, perhaps, two Sids. Should one of them revert to his original name? That could be difficult, for by now he would be well known by and thoroughly used to his new handle. And of course there was always the complication of reverting to ‘Pete’ when there might be a Pete there already.

One of these characters (I think his real name was Dave) became immortalised in the Middle Eastern Hunter world by virtue of ‘Bert’s Boat’ being named after him. It was common, when trying to rejoin a split formation, to nominate a geographical location over which to RV. For example, “I’m over Doha at 16,000ft in a left-hand orbit”. This particular Bert was, one day, trying to find his leader. “I’m over the big boat halfway down the west coast of Qatar,” he said. The other guy searched for ages but was unable to find any such boat. Eventually, the story has it, they gave up and returned independently to Muharraq. Naturally, the debrief was quite interesting, especially when they were forced to agree after much map study that the ‘big boat’ had most probably been the quite substantial island which lay more or less where they both thought they’d been. Ever afterwards, that lump of rock was known to successive generations of Middle Eastern Hunter pilots as ‘Bert’s Boat’ – and a very good RV it always proved to be. Certainly, its new name sounded better than ‘Dave’s Boat’.

Later in my RAF career we took very seriously the setting for a real or simulated war mission. The political background would be well known to us and would be touched on briefly, followed by the intelligence situation pertaining to the particular mission. But I don’t think that, on my first tour, we were at all politically aware. Most of our flying from Bahrain was of the training variety, but on the odd occasions when we received an operational task I don’t recall ever hearing any background to it. We knew, of course, that the UK had agreements with the Trucial States (broadly speaking, those states which would later form much of the UAE). And we were faintly aware of past unrest within the Jebel Akhdar region of Oman, the fighting during which the SAS had won its Middle-Eastern spurs. As far as we understood, things were generally quiet at the time we were out there, although renegades were known still to be provoking occasional skirmishing.

A 208 Squadron Hunter at low level over the Trucial States. The pilot is Terry Heyes.

But for whatever reason we were, from time to time, tasked with ‘flag wave’ sorties from Bahrain, down across the Akhdar with a landing at RAF Masirah. I remember being awed by the spectacularly wild and rugged terrain of the Jebel, with our little Hunters being dwarfed by mountains rising to almost 10,000 feet. The vistas of agriculture being scraped out on those high, rocky escarpments were simply extraordinary. And I also remember the mess steward on the bleak island of Masirah – a man whom many of us first-tourists recalled from our days at Valley for his magnificent night-flying suppers – serving us in the 40°C heat with doorstep corned beef sandwiches. Yes, they were memorable trips. But were those flag waves designed to reassure loyal Omanis – or to deter rebel groups? What prompted our tasking on those particular occasions? Were we successful? To this day I have no idea.

Similarly, in November 1970 we deployed at short notice to RAF Sharjah with the order to stand by for border patrols. The border in question was, I think, way down south of the Gulf between Abu Dhabi and Saudi Arabia – where today lies the southern extremity of the UAE. I say ‘I think’, because others with whom I’ve recently spoken recall the operating area as being up in the Musandam Peninsula. Whichever way, we were issued with loaded pistols to be carried in shoulder holsters, so it must have been serious. But at whom we should have aimed our pistols had we ejected I’ve no idea. What exactly the problem was and who was causing it I simply can’t recall – indeed I’m fairly certain that I never knew.

On standby for border patrol in 1970, the author dressed for action.

We were endlessly drilled in tactical formation flying, with the most strictly enforced principle being that, at low level, the element leader was responsible for the terrain clearance of both himself and his wingman. Therefore one never flew below the element leader. Generally speaking this was relatively easy to achieve (as long as you loosened your ejection seat straps, which allowed you to stretch and see more), but in certain situations it became a very demanding exercise. One such scenario was when a four-ship closed up into ‘arrow’ formation to manoeuvre through mountains and valleys. The leader was now responsible the author dressed for action.for the terrain clearance of all four, who would be spaced at approximately 200-yard intervals. A second principle which now came into play was that, as an added separation safety-break, nobody ever crossed to the opposite side of the arrow.

It all sounds simple, but now picture the entire ensemble wending its way at 420 knots up the bottom of a narrow, twisty, steep-sided valley. Imagine you’re number two on the inside of a turn as the leader cranks on seventy or eighty degrees of bank and pulls around the corner. Unlike in close formation when you stay in the plane of his wings, here you must fly above him. But you’re losing sight of him under your aircraft’s nose. You can’t slide to the outside of the turn to maintain visual because numbers three and four are there. The solution is to apply lots of bottom rudder, which cants the nose of your Hunter down and restores visibility – but you now need to hold off unwanted extra bank by applying out-of-turn aileron. What with the G in the turn, the crossed controls and the inevitable turbulence in the baking-hot, mountainous air it was a pretty uncomfortable way of flying. It was the sort of situation that would have given Biggles, in his Sopwith Pup, an unwanted blast of air on the side of his helmet which would make him correct the sideslip. The method was effective, though, and what we called ‘wadi-bashing’ was tremendous fun. It must, however, have placed unbelievable strain on the fin post and rudder, and I wonder whether Sir Sydney Camm ever anticipated his beautiful swept-wing interceptor being abused in such a way.

Compared with that, the endless high-level battle formation and cine gunsight-tracking exercises seemed much less exciting, but I guess they also stood me in good stead. Returning to low level, though, some of the weapons delivery profiles were quite hairy. I remember being amazed when, on the initial Hunter course, a series of bombing exercises taught me ‘50 foot level skip’ profiles. Fifty feet above ground level at 400 knots seemed helluva low and exciting, and I could hardly believe that I was being let loose in a Hunter to do this. In the Gulf we practised a variation, a 3° dive profile with a release planned for 75 feet above ground level. As I recall, the minimum authorised height for the recovery from the dive was 35 feet – which was even more helluva low! On one occasion, in the exceedingly hot and humid conditions, the hand of one of the first-tourists slipped off the stick during his 6G recovery and his jet efflux blew the target over. That certainly accounted for one of his nine lives.

To my knowledge we had no iron bombs out there, and that shallow dive profile was designed for the release of napalm – although I never saw or heard of any plan for the preparation of the real thing. Usually, we released small practice bombs, but on occasions there would be a few life-expired 100-gallon external fuel tanks available. These would be filled with...