![]()

1 Introduction

The research framework

In 2005, the members of the Scottish Wetland Archaeology Programme (SWAP) hosted the Wetland Archaeological Research Programme (WARP) conference in Edinburgh, bringing together practitioners of wetland archaeological research from all over world (SWAP 2007). In European terms, the timing of the conference was ideal; the major development of infrastructure in Ireland in the early 21st century had meant that some of the most important wetland discoveries had recently been made, while developments in continental Europe were continuing to push the boundaries of a long tradition of prehistoric settlement archaeology. Archaeologists specialising in wetland archaeology were developing new ways of integrating ‘wet’ and ‘dry’ sources of evidence to find alternative ways of thinking about wetlands (eg Van der Noort & O’Sullivan 2006), and both practical and theoretical aspects of the study of waterlogged archaeology were healthy and fertile grounds. As the home of Robert Munro, one of European wetland archaeology’s pioneers (Munro 1882; 1890) Edinburgh seemed an apt venue for an international gathering of wetland archaeologists, and the conference took the opportunity to celebrate Scotland’s rich wetland archaeological resource.

However, many of the papers presented at the conference (as well as others published subsequently) took the opportunity to highlight how little is in fact known about the extent and nature of wetland archaeology in Scotland (cf Crone and Clarke 2005; Henderson 2004). The theme of taphonomy explored in the session on lake dwellings served to highlight how our understanding of the mechanics of Scottish crannogs as archaeological sites was still at a very early stage, and as such that few reliable generalisations could be made (Cavers 2007; Henderson 2007a; Crone 2007). Several discursive syntheses had highlighted that meaningful interpretations of the role of wetland settlement in prehistory could only be made if these sites were considered an integral part of, not separate from the wider settled landscape (eg Henderson 1998; Harding 2000a), but by the early 21st century few inroads had been made and Scottish wetland archaeology seemed confined to the specialist periphery from which European practitioners had worked to break free (Coles & Coles 1996; O’Sullivan 1998; Fredengren 2002; Menotti 2012).

Acknowledging the dichotomy between the wealth of Scotland’s wetland resource and the lack of study of wetland sites, the then MSP for Culture, Tourism and Sport Patricia Ferguson tasked Historic Scotland with initiating a programme of research into wetland archaeology in Scotland, with the aim of redressing the peripheral role of waterlogged sites and artefacts in the study of Scotland’s past (SWAP 2007, ix). The first stage in this process was the compilation of a research agenda for wetlands (Cavers 2006a), which assessed the extent of our knowledge of the resource, and identified a series of primary research questions and themes designed to build on current understanding of activity in and around Scotland’s wetlands through history.

Previous studies have shown that, although peatlands comprise a major component of Scotland’s wetland environment, their archaeological potential is low, mainly because much of it is blanket bog and this was not intensively exploited in the past (Crone & Clarke 2005, 7). Occasional artefacts are found, buried in pockets of deeper peat but structures and trackways are very rare. The small areas of raised bog that survive do have more potential, as reflected in the discovery of the Neolithic platform on the edge of Flanders Moss (Ellis 2002), but assessments of other potentially significant bogs, Ballachulish (Clarke & Stoneman 2001), Moine Mhor (Housley et al 2007) and Achnacree (Clarke forthcoming), the latter two carried out as part of the SWAP programme, have yielded very little evidence of human activity.

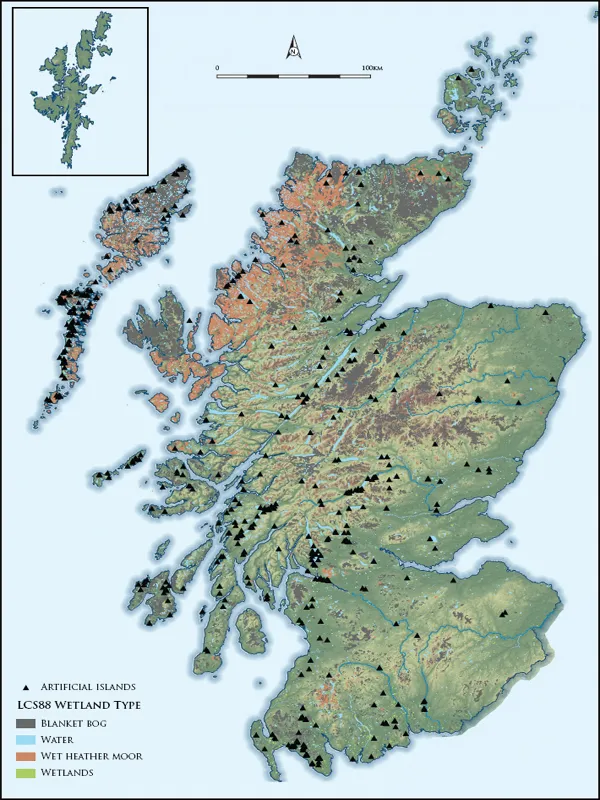

What Scotland does possess in abundance is evidence for the extensive use of open water, and particularly for the settlement of water bodies and their margins (Illus 1). Crannogs, or perhaps more generically loch settlements of all forms seem to have been a significant component of the settled landscape of Scotland from at least the middle of the 1st millennium BC through to the modern period, and there is evidence, from sites like Eilean Domhnuill in North Uist (Armit 1996) that the tradition of living on open water has much earlier origins. There are references to just under 400 ‘crannogs’ or related archaeological sites on islands in Scottish lochs, though, as is often acknowledged, the true number is very likely to be far higher than this, and where systematic surveys have been carried out (as in Lochs Tay and Awe; Morrison 1985; Dixon 1982), the number of known sites has been greatly increased. The impact of this element of historic settlement in Scotland has not been in proportion to the potential offered by the known levels of preservation typically encountered on these sites (Barber & Crone 1993), and 100 years after the publication of Munro’s Ancient Scottish Lake Dwellings only a handful of significant investigations had been carried out. The contribution of wetland settlement to wider archaeological understanding of prehistory and history remained obscure, limited to afterthoughts in the discussion of more significant settlement types.

The 2006 SWAP Research Agenda, then, placed the investigation of crannogs high in the list of priority areas for future research, with particular emphasis placed on understanding how the lake dwelling tradition had developed in Scotland, the role of crannogs in relation to the wider settlement system of prehistoric Scotland and how that role changed through time. The SWAP agenda undertook a geographical as well as thematic assessment of research potential, and identified the concentrations of loch settlements in Argyll and Dumfries and Galloway as key areas for further research. Among the key research themes was exploration of the relationship between wetland settlements and their contemporary ‘terrestrial’ counterparts during the later prehistoric centuries, the period when crannogs appear in large numbers in the archaeological record (Henderson 1998; Cavers 2006b; Crone 2012).

Illus 1. Distribution of artificial islands in Scotland

Three of the keynote projects undertaken during the first phase of fieldwork worked towards the investigation of this theme. The later Iron Age was approached through further fieldwork at Ederline crannog in Loch Awe, where previous excavations had demonstrated that the site, radiocarbon-dated by Morrison to the earlier Iron Age, was subsequently reoccupied in the mid–late 1st millennium AD, and may have been involved in redistributive trade with Dunadd (Morrison 1985; Cavers & Henderson 2005; Henderson forthcoming). Though the areas of the site investigated through excavation appear to relate exclusively to the late Iron Age/Early Historic phase of use, the earlier Iron Age dates obtained for timbers protruding from the top of the site provide an instructive taphonomic lesson, and the model developed as an explanation for this is an essential consideration in the interpretation of radiocarbon samples from submerged crannogs (see discussion by Cavers 2007; Crone 2007).

The later 1st millennium BC was explored through excavations at Dorman’s Island crannog in Whitefield Loch (Cavers et al 2011). This site, recorded during the SW Crannog Survey in 2002 and 2003 was known to be actively eroding, with rich organic deposits exposed on the eroding side of the site (Henderson et al 2003; Henderson et al 2006). Excavation was carried out on the above-water portion of the site, encountering substantial split oak logs and a prepared clay surface, probably representing the interior of a building. Fragments of a bracelet made from recycled Roman glass, as well as shards from a Roman glass vessel indicated activity at the site in the 1st or 2nd centuries AD, but the most significant result of the Dorman’s Island excavation was the determination of a dendrochronological date from the oak timbers. This date, giving a felling range of 153–121 BC, was the first prehistoric dendrochronological date obtained in Scotland, achieved through matches with master sequences from Northern Ireland and Carlisle, and immediately opened the doors for a new era of lake settlement research in Scotland (Cavers et al 2011). For the first time, there was a realistic prospect of disentangling the superimposition of occupation phases on prehistoric crannogs, and improving on the ill-defined dating of activity on Scottish crannogs through the 1st millennium BC.

The promontory in Cults Loch (Cults Loch 3 – see note on site labels below) had attracted attention during construction of the SWAP research agenda for two reasons. Firstly, the radiocarbon date obtained from an oak stake sampled in 2004 was relatively early in the Scottish lake settlement chronology, calibrating in the period 550–200 cal BC (GU-12138), and secondly, the form of the site was unusual. The oak stakes encircling what appeared to be a stony natural promontory in the loch was an arrangement unlike any other crannog known in Scotland, and had raised the possibility that the site represented the remains of a loch-side dwelling of the type apparently widespread in Ireland (eg O’Sullivan 1998) but hitherto unknown in Scotland. Coring carried out during the first phase of the SW Crannog Survey in the late 1980s (Barber & Crone 1993) had recovered charcoal and burnt bone from deposits on the promontory, raising the prospect that occupation deposits were preserved that could be related to the perimeter stakes, so that the site was shortlisted as a candidate for the investigation of the origins of the lake settlement tradition in Scotland.

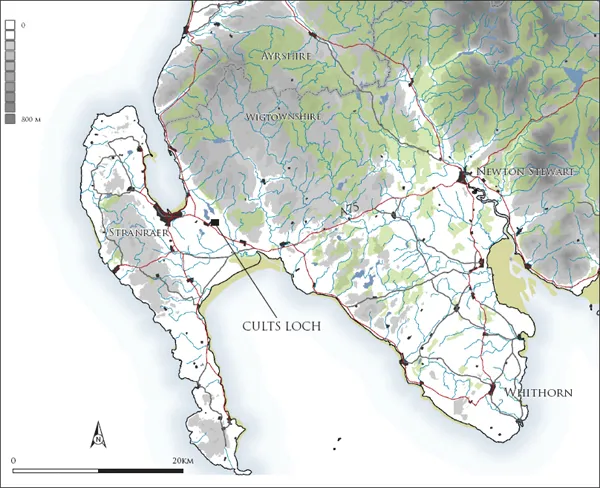

Cults Loch is located on the Luce isthmus of Galloway, a narrow stretch of low-lying land separating the Rhinns from the Machars (Illus 2). The area constitutes some of the best-quality agricultural land in Wigtownshire, and has apparently always been a focal point for settlement. The rich cropmark record of the surrounding fields (Illus 3), one of the RCAHMS’s key ‘honeypots’ in SW Scotland (Cowley 2002), demonstrated that Cults Loch, with the adjacent Black and White Lochs to the west and Soulseat Loch to the south had been at the centre of a densely settled landscape throughout the later prehistoric period, and was surrounded by evidence for multiple ditched and palisaded enclosures at Sheucan and Chlenry (Cults Loch 5) and a fort on the opposing side of the loch (Cults Loch 4), as well as probable barrows of unknown date at Balnab. In addition to these ‘terrestrial’ settlements, radiocarbondating of the crannog surviving as an island in the centre of Cults Loch (Cults Loch 1) had demonstrated activity there in the Roman centuries (cal AD 120–390; GU-10919), while antiquarian investigations at the artificial islet in Black Loch (Loch Inch-Crindl) had produced artefacts suggesting a late Iron Age or early historic occupation of that site (Dalrymple 1873). The opportunity, therefore, was presented for the investigation of settlement evolution and development through the Iron Age, with the investigation of the role of the Cults Loch promontory central to the exploration of the development of lake settlement and its relationship with contemporary and successive terrestrial sites. The presence, furthermore, of an area of deep peat to the NW of Cults Loch offered the prospect of an associated multi-proxy environmental investigation, correlating peatcore evidence with the nearby archaeological record.

The Cults Loch area, therefore, appeared to offer the opportunity to explore what circumstances had resulted in the choice of settlement in water, within a landscape that was otherwise populated by typical later prehistoric settlements. Could the construction of crannogs be tied to discrete chronological horizons, which might draw the conclusion that their presence was related to certain socio-political conditions, were there functionally-specific reasons for building on or near water, or were less practical factors in play? During the course of the Cults Loch programme, further reasons for requiring a ‘landscape’ approach to these questions emerged, when the dendrochronological dates from work on south-western material began to suggest that crannog construction activity might fall into episodic horizons noted in Irish material (Crone 2012), so that the apparent ubiquity of crannog occupation throughout Scottish prehistory might be misleading. Only contextualised, multi-site investigation could test hypotheses like these, and it is certain that further work will be required to explore these possibilities.

Illus 2. Location of Cults Loch

The landscape setting; geology and hydrology

Cults Loch lies on the eastern edge of ...