![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Value SPC Can Add to Quality, Operations, Supply Chain Management, and Continuous Improvement Programs

We don’t like volatility. Nobody likes volatility.

—Lionel Guerdoux Managing Partner,

Capricorn Venture Partners

Uncertainty is something organizations struggle to deal with. A few examples of devices organizations use to cope with uncertainty include pro formas, which are prepared for a variety of contingencies; forecasts that are created with confidence intervals to assess the magnitude of uncertainties; production planning, which often involves an attempt to predict the range of unpredictable possibilities that render the plan obsolete on a nearly daily basis; and order quantities that include safety stock.

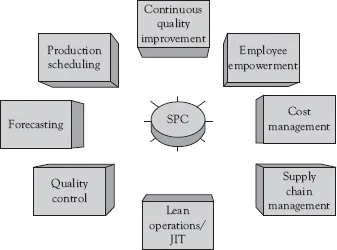

Statistical process control (SPC) is defined by the American Society for Quality as “the application of statistical techniques to control a process.”1 Properly employed, SPC can be a significant factor in the control and minimization of variation and the resulting uncertainty in the manufacture of products and the delivery of services. It can greatly reduce the time it takes to recognize problems and provide useful information for the identification of root causes of those problems. The result often is better quality and lower costs.

SPC is also useful in demonstrating that a process is capable of consistently delivering what the customer wants. For this reason, some organizations require their suppliers to use SPC in order to become preferred suppliers. SPC also can provide conclusive evidence for the effectiveness of continuous process improvement programs (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 SPC adds value to business processes

From Chaos to Control

Often the first step in implementing SPC for a process is to construct a control chart for the process as it currently exists. Frequently, this base line control chart will show the process to be chaotic and unpredictable or, to use SPC terminology, out of control. While this might come as a surprise to management, it often is not surprising to those charged with running the process, scheduling the process, and evaluating the quality of the products and services resulting from the process. However, the real issue is that prior to constructing the chart, the state of control of the process was unknown. How can one possibly make forecasts, schedules, or predictions about quality based on the unknown?

The control charts used by SPC to assess the state of control of a process should be created when the process is performing as designed. The team responsible for implementing SPC should assure that the equipment is in good working order, is being operated by trained personnel, the settings are correct, and the raw materials meet specifications. The resulting control chart is an empirical statistical model of how the process can be expected to perform so long as it is operating as designed. The control chart reflects the expected level of variation for the process and we say that the process is operating in control. When other sources of variation occur, such as a defective lot of raw material, a machine malfunction, an incorrect setting, or a poorly trained operator, the control chart typically provides a signal indicating that the process is no longer performing as designed and we say the process is operating out of control.

SPC is designed to be used in real time. This means that samples (often referred to as subgroups) are taken from the process as the product is being produced, the samples are inspected, the data plotted on a control chart, and the state of control of the process assessed within as short a time span as possible. The same process is used when applying SPC to services. Samples should be taken as close to the time of delivery of services as possible. Timely sampling is necessary since a stable, predictable, in-control process can drift out of control. However, with real-time SPC, the length of time it takes to identify this condition and correct the problem can be minimized. So, with SPC, we work with predictable processes and monitor those processes in real time to ensure that they remain in control. In this way, SPC significantly minimizes the uncertainty associated with those processes.

SPC and Production Scheduling

During the sales and operations planning process, production plans are created to meet sales forecasts and other organizational objectives. Production schedules are created to meet the production plans and are often based on standards contained in manufacturing master files. While these standards are sometimes based on historical averages, they are most often based on engineering assessments of the effective capacity—that is, the sustainable production rate with allowances for personal time and maintenance2—for the process. Creating production schedules from standards based on effective capacity assumes the process is behaving as it was when the production rates were set. Production schedules based on historical averages assume the process is currently performing as it has done in the past. Both assumptions are simply acts of faith (and often vain hopes) when the state of control of the process is unknown. The only way to systematically monitor and assess whether these assumptions are valid is through the use of SPC.

A process proven to be in control through the use of SPC is predictable. A process shown to be out of control using SPC is unpredictable. A process running without SPC is an unknown quantity. So it should not be surprising that production schedules for processes whose state of control is unknown often are “not worth the paper they are printed on,” as one production supervisor put it. Without the predictability that SPC provides, there is more chaos and uncertainty, more stress, extra meetings, missed schedules, and additional overtime, which contribute to increased cost, reduced productivity, excessive built-in allowances for uncertainty, and impaired employee satisfaction. Additionally, employee confidence in management and those ultimately responsible for drafting unrealistic production schedules may be affected.

SPC will not assure that a process always operates in a state of control and thus be predictable. However, SPC is designed to be run in real time, which will be discussed in more detail later in this chapter. This ensures that out of control conditions are detected in a timely manner and current information is made available to troubleshooters who are assigned to find and correct the problems that SPC indicates are present. Timely detection coupled with effective and timely troubleshooting and problem correction can prevent the out of control condition from persisting for long periods of time.

SPC and Forecasts

Forecasts are essential to organizational planning and decision making and, the more accurate the forecasts, the more accurate the plans and decisions. Inaccurate forecasts of revenue and profit can result in significant loss of stock value for a corporation. Inaccurate production and labor forecasts can cause significant disruptions within operations. The inaccuracies in operations forecasts can ultimately contribute to inaccuracies in forecasts of revenues and profits. If we fail to produce what we forecast, revenues will suffer. If we fail to produce at the cost we forecast, profits will suffer.

Forecasts based on time series analysis of past data assume that the causal system that created variation in the value of what is being forecast will continue to do so in the same way in the future. While SPC cannot affect the external influences that can alter the causal system (e.g., changes in consumer taste, availability of new technologies), it can increase the accuracy of forecasts by decreasing the variation in processes upon which the forecasts are based. When the causal system underlying a forecast is comprised of processes that are out of control, forecast accuracy is greatly diminished. Indeed, a term used to describe such forecasts is not worth the paper they are written on. How can a forecast based on unpredictable processes be anything but inaccurate?

Example 1.1

Why are We Always Missing Deadlines?

Once again the question arises in the staff meeting: Why are we late on so many shipments? The forecast called for the production of 100 products per hour by the process. Production records indicate this forecast was met. Yet, the product is not ready to ship. Investigation shows that much of the product produced is either awaiting inspection or has been rejected and is awaiting rework.

One problem is that the forecast was based on standard production rates, which assume and account for some standard defect rate. However, since the process is in an unknown state of control, there is considerable variation in defect rates, resulting in considerable variation in the rate of production of acceptable product ready to ship. In this case, considerably more defective product was produced than the forecast allowed for.

Late deliveries can be a source of customer dissatisfaction as well as hurting the profit and loss (P&L). Often the answer is that the product was produced on time according to the schedule based on the forecast. But instead of being in the finished goods warehouse ready to ship, some or all of the products are awaiting inspection by quality control (QC) or have been rejected and are awaiting rework. Worse yet, the process may be shut down while engineering and maintenance technicians try to determine why so many defective products have been produced. No wonder the production forecast wasn’t worth the paper it was written on, and the actual P&L is worse than the pro forma.3

Process instability and poor capability of the process to consistently produce products that meet specifications can result in considerable variation in product quality. Variations in the lag time between production and inspection can make troubleshooting process problems more difficult. Implementation of SPC brings processes into control and can provide reliable estimates about the state of the processes. The result will be more reliable standard production rates that can support more accurate production forecasts. When combined with continuous improvement activities, SPC can help minimize process variation and increase the capability of the process to meet specifications resulting in an increased ability to meet forecasts and shipment commitments. More importantly, customers will be happier and the P&L will look more like the pro forma.

When SPC is used to bring the causal system processes into control, forecast accuracy will typically increase as well. Because common cause variation is still present in an in-control process, it is impossible to provide perfect input to forecasting models. Perfection, while desirable as a goal, can never be achieved in a forecasting model. However, perfection in a forecast is seldom necessary to achieve the objectives of the forecast. Most would agree that an accurate but imperfect forecast provides a much better basis for decision making than one not worth the paper it is printed on.

SPC and Quality Control

The output of processes must be assessed for quality in some way. Typical end-of-line inspection processes where the output is collected into lots and assessed using some form of acceptance sampling suffer from several flaws. The first flaw is the delay between the time a product was produced until the time the inspection occurs. I have observed cases where the lag period between production and inspection was measured in days. So, if a problem is detected in a lot, the process that produced the lot may have run in much the same way producing defective products throughout the entire lag period. This can result in a considerable quantity of potentially defective material, which must be subjected to more extensive inspection, possible rework, downgrade, or scrap. I have observed plants where a great deal of space is occupied by pallets of material awaiting inspection. Frequently, these plants have large rework departments to sort through rejected lots of material and correct defects where possible. This excess inventory and non–value-adding operations are the result of uncontrolled processes and significant lag time between production and inspection.

A second flaw is that acceptance sampling plans simply provide a lot disposition (accept or reject) and, unlike SPC, cannot provide evidence about the state of control of the process that produced the lot. SPC, unlike acceptance sampling, controls the quality of the output by providing information to allow control of the process. SPC provides the means to develop capable and in-control processes that produce product that is more uniform and predictable in quality.

SPC and Lean Operations or Just-in-Time

ASQ defines lean as “producing the maximum sellable products or services at the lowest operational cost while optimizing inventory levels” and just-in-time (JIT) as “an optimal material requirement planning system ...