Kennan had almost no experience with East Asian affairs before he became director of the Policy Planning Staff (PPS) in May 1947. He had never been in the Far East, nor, by his own account, had he ever been particularly interested in it. Even after he left the PPS in 1951, he claimed he had “no personal familiarity with that part of the world” and had “read no more [about it] than a busy person, not an expert on Far Eastern affairs, can contrive to read in the face of other interests and obligations.”1 Kennan nonetheless had forged elements of a strategic perspective on East Asia—and some preconceived notions—that were largely derived from professional colleagues who greatly influenced his initial thinking about the region.

He was aware that his distant relative and namesake George Kennan (1845–1924)—whose career the younger Kennan emulated in part—had some experience with the Far East. The elder Kennan (the first cousin of George F.’s grandfather) was an explorer and writer best known for his travels in Russia, especially Siberia, but was also engaged as a journalist during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–5. Citing the similarities between their careers, George F. Kennan noted in his memoirs that both he and his distant cousin “had occasion to plead at one time or another for greater understanding in America for Japan and her geopolitical problems vis-à-vis the Asian mainland.”2 But this influence on Kennan’s perspective on the region was superficial at best, and his own pleading on Japan’s behalf came only later.

The MacMurray Memorandum

Of more profound importance in framing Kennan’s mind-set toward East Asia was the influence of a senior US Foreign Service colleague and fellow Princeton graduate, John Van Antwerp MacMurray (1881–1960), who had served as US minister to China from 1925 to 1929. MacMurray was a generation older than Kennan, but they briefly served together abroad in 1933, when MacMurray was appointed minister to the Baltic States, resident in Riga, Latvia—where Kennan was then serving in his first diplomatic assignment. Almost immediately, however, Kennan was transferred to the newly opened US embassy in Moscow.3

Washington, meanwhile, was grappling with the crisis in East Asia that had been sparked by the Japanese invasion of Manchuria (northeastern China) in 1931. In 1935, MacMurray was tasked by the State Department to contribute an assessment of the situation there, based on his long-standing experience and expertise on the region. The memorandum he produced—“Developments Affecting American Policy in the Far East” (1 November 1935)—was largely neglected at the time it was written but was later recognized both inside and outside the State Department as a seminal document.4 Indeed, MacMurray’s memorandum and Kennan’s own February 1946 “Long Telegram” from Moscow assessing Soviet foreign policy were considered by some to be the two best analytical reports ever produced within the department.

Although it is not clear precisely when Kennan first encountered the MacMurray memorandum, records show that it was circulating among State officials involved with East Asia policy during the years 1947–50, when he was PPS director; Kennan shortly thereafter told MacMurray he “stole” a copy as an “indispensable aid” when he left the department. Kennan later acknowledged that the memorandum made a “deep impression” on him, and it became an enduring foundation for his approach to East Asia.5

The central thesis of MacMurray’s memorandum was that the Far Eastern crisis of the 1930s was largely the result of China’s failure to abide by its commitments in the framework for regional security cooperation that had been embodied in the Washington Naval Conference treaties of 1922, and Washington’s failure to press China to do so.6 Those commitments included China’s obligation to avoid discrimination in “dealing with applications for economic rights and privileges from Governments and nationals of all foreign countries.”7 In MacMurray’s view, Japan had acted militarily to secure its interests in northern China only after repeatedly but unsuccessfully seeking the help of the United States and other Western powers in forcing the Chinese to act responsibly. In his prescient conclusions, MacMurray predicted that war between the United States and Japan was inevitable if Washington chose to oppose Japanese domination of China.

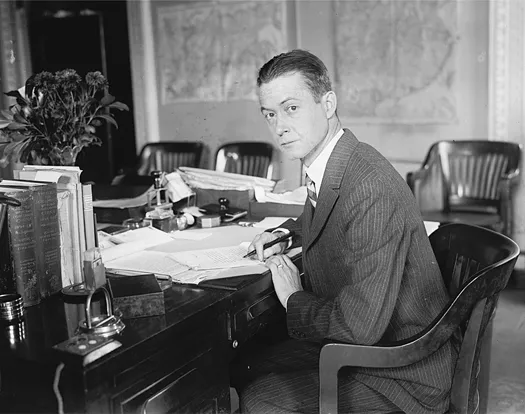

John Van Antwerp MacMurray as assistant secretary of state, 1924. MacMurray was the primary source of Kennan’s assessment of the relative strategic importance of China and Japan.

Source: Library of Congress / Prints and Photographs Division

Many of the themes outlined by MacMurray in the 1935 memorandum would later be echoed repeatedly in Kennan’s own thinking and writing. Foremost among these was MacMurray’s characterization of US attitudes toward China and the extent to which the Chinese exploited them. He observed that Americans harbored strong sentimental attitudes toward China that were “based upon rather naive and romantic assumptions” whose “vigor and intensity seemed out of all proportion to the average citizen’s concern with Chinese affairs.” This popular attachment to the Chinese was “based in part upon a somewhat patronizing pride in the belief that our Government had borne the part of China against selfish nations, but still more upon the fact that our church organizations had through several generations cultivated a favorable interest in China in support of their missionary enterprises therein.”8

MacMurray considered the missionaries and other adherents of a sentimental attachment to China to be dupes for the Chinese inasmuch as they became a powerful lobby pressuring the US government to defend China’s interests. The Chinese, for their part, were more than willing to accept the favor—but without incurring any obligations or showing any gratitude. Indeed, MacMurray felt that the Chinese had virtually asked for whatever pain they suffered at the hands of Japan and other outside powers:

The Chinese … had been willful in their scorn of their legal obligations, reckless in their resort to violence for the accomplishment of their ends, and provocative in their methods; though timid when there was any prospect that the force to which they resorted would be met by force, they were alert to take a hectoring attitude at any sign of weakness in their opponents, and cynically inclined to construe as weakness any yielding to their demands. Those who sought to deal fairly with them were reviled as niggardly in not going further to satisfy them, and were subjected to difficulties in the hope of forcing them to grant more; so that a policy of appeasement and reconciliation, such as that with which our own Government attempted to soothe the hysteria of their elated racial self-esteem, brought only disillusionments.9

Nor did MacMurray believe that US efforts to extract Japan from China would endear the Chinese to the United States:

The Chinese always did, do, and will regard foreign nations as barbarian enemies, to be dealt with by playing them off against each other. The most successful of them might be respected, but would nevertheless be regarded as the one to be next put down.… If we were to “save” China from Japan and become the “Number One” nation in the eyes of her people, we should thereby become not the most favored but the most distrusted of nations. It is no reproach to the Chinese to acknowledge that we should have established no claim upon their gratitude.… They would thank us for nothing, and give us no credit for unselfish intentions, but set themselves to formulating resistance to us in the exercise of the responsibilities we would have assumed.10

Strategically, MacMurray believed that US policy toward China, starting with the “Open Door Notes” of then Secretary of State John Hay in 1899–1900, had been based on a specious assumption of the potential value of US trade with China and on Washington’s consequent but unenforceable support for China’s territorial integrity as a prerequisite for ensuring free access to trade with it. This, in MacMurray’s view, overestimated China’s strategic importance and underestimated the risks of engaging with it by failing to recognize that China was not a consequential nation but instead “a mere congeries of human beings, primitive in its political and economic organization, difficult and often troublesome to deal with in either aspect, and by its weakness constantly inviting aggressions that threatened such interests as we might have or hope for.” As far as US interests were concerned, Washington needed to recognize that China had “ceased to be, for us, a field of unlimited opportunity, and seems in the way of becoming a waste area” and “an almost negligible factor” in East Asia.11

In contrast, MacMurray insisted that Japan was the consequential nation in East Asia and should be the center of US policy there: “a working theory of the relative importance of the various objectives in our Far Eastern policy” would dictate that “Japan has come to be of paramount interest to us.” Accordingly, Washington needed to “write off our claims to leadership” in China and acknowledge that the “virile people” of Japan were the strategic key to the region. MacMurray acknowledged that Japan itself was potentially volatile and that a precipitous US abandonment of China “would buy us no reconciliation with the Japanese, gain us no respect, and ease none of our difficulties.” Accordingly, he advised that Washington should “be meticulously careful not to lose the wholesome respect with which the Japanese at heart regard us, by any attempt to ingratiate ourselves with them by compromising our own national power or dignity or principles.” Nonetheless, MacMurray’s bottom line was that the United States needed to “write down our interest in China to its present depreciated value,” adjust US policies to accommodate the real balance of power in East Asia, and acknowledge the limits of US interests and influence there.12

The central themes and the analysis contained within MacMurray’s memorandum have been the subject of persistent debate among historians, particularly those focused on the origins of World War II in East Asia.13 However, an assessment of the validity of his judgments about Chinese and Japanese policies during the 1920s and 1930s is beyond the scope of this book. In any event, much of his analysis was overtaken by subsequent events and the Pacific War itself.

Nonetheless, when Kennan encountered the MacMurray memorandum, probably more than a decade after it was written, he was wholly won over by MacMurray’s analysis and the power of his prose. He considered the memorandum “extremely thoughtful and prophetic” and wrote to MacMurray: “I know of no document on record in our government with respect to foreign policy which is more penetrating and thoughtful and prescient than this one. It was an extraordinary work of analysis and of insight into the future; and it is a disturbing reflection on the ways of our government that it failed to leave a deeper mark than it did on the minds of those to whom it was presented and who had access to it at the time. It has done a great deal to clarify my own thinking on Far Eastern problems.”14 Decades later Kennan wrote that he “would put M[acMurray]’s paper among the rare great state papers of this century, comparable to Sir Eire [sic] Crowe’s famous memorandum of 1907 in the British Foreign Office documents—but even better.”15 He quoted MacMurray on multiple occasions, and ideas and even language traceable to the MacMurray memorandum are clearly evident in Kennan’s analysis and commentary on East Asian affairs from the beginning of his tenure as PPS director and indeed through the rest of his life. His own analytical and writing style may even have been influenced by MacMurray’s.16

Kennan first cited MacMurray publicly in his 1951 lecture “America and the Orient”—later published in American Diplomacy—which borrows multiple themes from MacMurray’s 1935 memorandum. In assessing the evolution of US policy toward China from the Open Door Notes forward, Kennan highlighted what he considered an ill-advised emphasis on moral principles and emotional sentiment rather than strategic calculations in dealing with East Asia in general and China in particular. In criticizing the Open Door Notes—none of which, as he had observed in an earlier lecture, “had any perceptible practical effect”—Kennan lamented that the “tendency to achieve our foreign policy objectives by inducing other governments to sign up to professions of high moral and legal principle appears to have a great and enduring vitality in our diplomatic practice.” In the Far East, he observed, this “seems to have achieved the status of a basic diplomatic method, and I think we have grounds to question its soundness and suitability.”17

Echoing MacMurray, Kennan argued that the Open Door Notes’ principled emphasis on upholding China’s territorial and administrative integrity was bound to conflict with valid Japanese interests in China—and thus risked alienating Japan in favor of China, which did not merit US patronage and protection. He thus credited MacMurray with predicting the war with Japan, which might have been avoided: “I can only say that if there was a possibility that the course of events might have been altered by an American policy based consistently, over a long period of time, on a recognition of power realities in the Orient as a factor worthy of our serious respect … then it must be admitted that we did very little to exploit this possibility.”18

Both Kennan and MacMurray appear to have somewha...