![]()

CHAPTER 1

Mexico’s Ecological Revolutions

Chris Boyer and Martha Micheline Cariño Olvera

The state has acted as the primary mediator between nature and society in Mexico. This is not because its power and stability have made possible control of the social or economic practices of people, businesses, or bureaucratic entities within its borders. Nor has it been a powerful state characterized by its ability to direct the country’s political, economic, and ecological destiny. Rather, the Mexican state’s influence is the result of governments and changing political circumstances that have created opportunities for various groups of actors in different historical periods, with profound consequences for the nation’s population and territory. The state has also experienced radical changes due to the establishment of militant liberalism in the nineteenth century, the social revolution of 1910, and the resurgence of development liberalism beginning in the mid-twentieth century. Transitions from one period to another nearly always have been sudden and unforeseen. In other words, the country has not only experienced a series of political revolutions, but also various “ecological revolutions,” in the sense proposed by Carolyn Merchant: dramatic changes in the way people conceive and make use of their surroundings and the country’s so-called natural resources.1

These ecological revolutions arose in a context of growing—though discontinuous—commodification of nature and in increasingly precarious environmental conditions. Nevertheless, in many specific cases they have given rise to sustainable uses, and even to new sustainable uses, of territory and resources.

Beginning in 1854, when the state began to consolidate, up to the present, Mexican territory went through three stages that led to ecological revolutions: the political-liberal movement that erupted in Ayutla in 1854, the social revolution of 1910, and the so-called Green Revolution that began in 1943 and that presaged the neoliberal period beginning in 1992. None of these revolutions completely broke with prior ecological, social, and political conditions, yet each generated new circumstances in which each social group that used natural resources came to new understandings about their surroundings and were likewise affected by changes in the environment. Each revolution left long-term social and ecological footprints, creating the context that led to the following revolution. But each revolution also created countercurrents, that is, historical dynamics capable of counteracting the effects of the revolution itself which, in the long term, constituted unexpected openings for groups and individuals to value and use nature, creating new forms of social organization.

Nineteenth-century liberalism cemented private property’s hegemony, opening new investment possibilities leading to the increasing commodification of natural resources. Thus, it contributed to the neocolonial extractive regimen that characterized the regime of president Porfirio Díaz (1876–1911, known as the Porfiriato), which was characterized by the sacking of minerals, water, forests, and oil by predominantly foreign interests. The social revolution reorganized landholding and permitted its collective use, though neither private property nor the intensive use of natural resources was eradicated. These were subject to a new period of exploitation with the Green Revolution, whose ostensible goal was to promote small-scale agriculture but ultimately favored private landholders and commercial production. As the years passed and with the advent of neoliberalism, market forces became stronger, putting an end to the accomplishments of the 1910 revolution and producing a new wave of commodification in fields, forests, rivers, seas, mines, and on seashores. The commodification of nature has gone hand in hand with an increase in the dispossession of peasants, fishermen, and indigenous communities, thereby sharpening social inequality. The cities overflow with migrants who are hard put to find work even in the informal economy. Insecurity grows, as does pollution in both urban and rural areas.

This situation explains the increase in popular mobilizations of people fed up with the growing power of the transnational corporations that increasingly have acquired control of the nation’s natural resources. In response to the widespread reprivatization of land and aquatic ecosystems experienced in the country, since the year 2000 an unprecedented phenomenon has appeared: the slow but unmistakable strengthening of a rural-urban alliance proposing alternatives to the overexploitation of natural resources and the use of genetically modified organisms, and opposing the dismantling of campesino agriculture. These same movements seek new ways to reconstruct the country on the basis of its biocultural wealth and diversity.

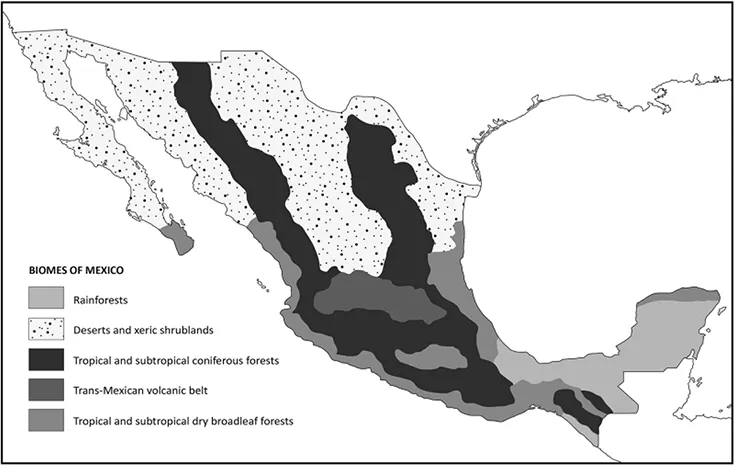

Biocultural Sketch

Mexico is the world’s eleventh most populated country, with more than 119 million inhabitants as of 2014. It is categorized as one of the world’s twelve megadiverse countries according to Conservation International. Thirteen percent of the nation’s territory is located within 177 protected areas, including biosphere reserves, national parks, natural monuments, natural resource protected areas, flora and fauna protected areas, and sanctuaries. In terms of GDP, it is the world’s fourteenth largest economy, but is in the sixty-first place in the terms of the Human Development Index. It is a federal republic composed of a capital city and thirty-one states. It has been and continues to be a rich country in natural and cultural terms, blessed with five major biomes, as illustrated in map 1.1. Its wide variety of ecosystems has historically translated into an enormous diversity of production strategies. One of the most important examples is the ancient peasant custom of selecting grains of corn from plants with the most desirable qualities. For the nine thousand years since the domestication of Zea mays in the Balsas river valley, maize has spread throughout Mesoamerica, and farmers have produced forty-one landraces and more than a thousand local varieties. This extraordinary agrodiversity is the result of seed selection by farmers looking for those best adapted to the microclimatic conditions of their territories. As a result, the agrodiversity of corn is closely related to the diversity of the country’s indigenous societies, which currently speak no fewer than sixty-seven autochthonous languages.2

Map 1.1. Mexico’s main biomes.

Source: Anthony Challenger, Utilización y conservación de los ecosistemas terrestres de México. Pasado, presente y futuro (Mexico City: UNAM/CNCUB, 1998), figures 6.2 (p. 278) and 6.3 (p. 280). Simplified version by Camilo Uscátegui.

Unsurprisingly for a country with such a wide variety of climates and cultures, it is divided into myriad biocultural regions with socioenvironmental characteristics that have marked both their own history and their place in the country’s evolution. Beginning at the Mexico–United States border, the great Mexican north is an arid space that opens toward the northwest, toward the long Baja California Peninsula and the Gulf of California—which Jacques Cousteau once called “the world’s aquarium”—the only sea owned by a single nation. Most of the north is occupied by the Sonora Desert phytogeographic region, one of the Americas’ four largest deserts, but one outstanding for its rich biodiversity. Given the territory’s aridity and vast size, the northern states have a low demographic density compared to those of the center and south of the country. Nevertheless, it is also there, and especially near the border, where some of Mexico’s largest and most industrial cities are located: Tijuana, Mexicali, Hermosillo, Nogales, Ciudad Juárez, Monterrey, Torreón, Saltillo, and Tampico. The north is a region of vast plains and high mountains. In the former, large herds of cattle once roamed the enormous haciendas that were the special target for agrarian distribution during the Mexican Revolution. Since the 1960s, it has been the Green Revolution’s favored territory due to its flat topography and abundant water sources for agroindustrial development. In the latter, logging and mineral mining—especially copper in Cananea in Sonora and El Boleo in Baja California Sur—have driven a dynamic economy and polluted soil and water ever since the nineteenth century.

The center of the country is marked by highlands where the Sierra Madre Occidental and Oriental cordilleras come together. Here the old colonial cities are located, many of them World Heritage sites: Morelia, Guanajuato, San Luis Potosí, Querétaro, Puebla, Tlaxcala, and Mexico City. Toward the south, the cordilleras join in the Mixtec Range and are interrupted by a depression that forms the Tehuantepec Isthmus. The highlands and their valleys have been densely populated since the pre-Hispanic epoch by different indigenous groups, who in the colonial era were often forced to work in the region’s gold and silver mines. As population and power centers, these sites have been the stage for important events in the nation’s history, especially during the Independence War, the War of the Reform—as the liberal revolution is known in Mexican historiography—and the Mexican Revolution. For example, the independence struggle (1810) was planned in Querétaro, and it was there that Maximilian of Hapsburg faced the firing squad (1867) and the current Constitution of 1917 was written and signed. The Mexico City metropolitan area, with more than twenty million residents, is among the world’s largest megacities. In spite of pollution and constant changes in land use, the central mountains and valley still have large conifer forests, which, in addition to providing lumber and cellulose, are partially protected in parks and reserves. The area is also rich in archeological sites and many communities whose residents maintain their indigenous culture.

In the east, under the tropical influence of the Gulf of Mexico, are the Huasteca Mountains with their forest microclimates. In the sierras of Puebla and Veracruz are the coffee-producing regions—organic, for the most part—and the areas that still contain the greatest corn diversity. In the Gulf of Mexico lie the largest oil deposits, and this black gold continues to lead Mexico’s exports. In the west, the Pacific coast forms a rich plain, and the coastal area includes an abundance of lagoons, mangroves, beaches with palm stands, and tourist centers, including those with a long history, such as Acapulco, as well as new sites like Huatulco. Also in this area are Mexico’s largest ports: Ensenada, Mazatlán, Manzanillo, Lázaro Cárdenas, Salina Cruz, and Puerto de Chiapas.

In the south are the states with the widest biocultural diversity: Guerrero, Oaxaca, Chiapas, Tabasco, Campeche, Yucatán, and Quintana Roo. The last three form the Yucatán Peninsula where the calcareous plain is the site of an intricate complex of underground rivers that produce natural open air wells known as cenotes. Here too rises the Petén forest, where Mayan ruins and communities abound. The seven southern states contain exuberant tropical ecosystems whose biodiversity varies from the high mountains to the coast. They also contain invaluable archaeological wealth at numerous large sites of the Mixtec, Zapotec, Olmec, and Maya cultures. There are also beautiful beaches on the Pacific Ocean, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Caribbean Sea, with countless coastal lagoons, mangroves, bays, islands, and tropical reefs, including the Mesoamerican Reef, which ranks as the world’s second largest, and nearly sixty protected areas (35 percent of Mexico’s total). These are also the states with the largest number of indigenous groups and languages. This wealth has constantly attracted those who seek to exploit the land, the coast, the seas, and the subterranean minerals. Since colonial times, large landed estates have been concentrated in this area, monocultures have been introduced, tons of timber have been extracted, enormous hydroelectric dams have been built, and the coast has been plagued by resorts closed to the majority of Mexicans whose annual income would not pay for a single night’s stay.

Mexico’s location within world geopolitics has been a key factor in its environmental history. Ever since the colonial era, the country’s two ocean fronts have joined Asia to Europe, facilitating colonial Spain’s interoceanic communication and making Mexico the most important colonial administrative center; meanwhile, Mexico’s natural resource wealth (silver, especially, but also other precious commodities such as cochineal, pearls, and cacao) had an influence on the location and development of human settlements and the institutionalization of an economy based on extractivism. Since the mid-nineteenth century, proximity to the United States has been a decisive factor in the development of another productive wave based on mining, livestock, and large-scale agriculture, especially in the north. Today, the two countries share the world’s longest terrestrial border between the global North and South. The border, physically marked by a fence and by the Río Grande has become one of the globe’s most dynamic frontier areas. Tons of merchandise—legal and illegal—cross the border between the two trading partners. Millions of people also cross, including both documented and undocumented migrants hailing from Mexico but also from Central and South America.

Mexico is a country of contrasts and contradictions, which have turned into socioenvironmental conflicts whose historical trajectories have culminated in the ecological revolutions analyzed in this article.

The Political-Liberal Revolution: From Mexican Independence to the Fall of the Porfiriato

The extractive regime of the colonial economy was destroyed by eleven years of armed movements, beginning with the rebellion led by Miguel Hidalgo in 1810 and ending with Agustín de Iturbide’s military uprising in 1821. The major mines (in Zacatecas and San Luis Potosí) flooded, and a half century passed before the mining industry recovered. The sector’s decline temporarily ended the environmental damage caused by colonial mining, allowing forests to recover for several decades. Ever since the sixteenth century, exploitation of precious metals had caused deforestation around mineral deposits, the extraction and refining of which required increasing quantities of wood. Mining was also the force behind the development of businesses providing supplies, such as the charcoal haciendas and the small-scale charcoal sellers.3 As Robert C. West demonstrated more than sixty-five years ago, the variety and scale of inputs that the mines required multiplied their ecological impact, and this influenced the location of human settlements and the use (and overuse) of forest, hydraulic, and agricultural resources, and thus determined the socioenvironmental history of various desert areas in the north of the country.4 With the outbreak of the independence wars at the beginning of the nineteenth century, insurgent and royal armies sacked the haciendas in...