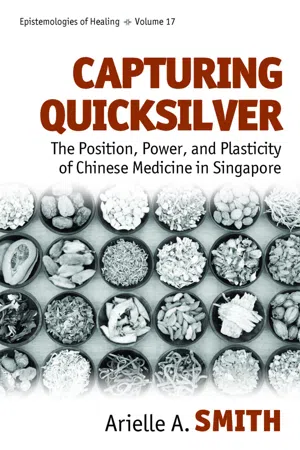

![]()

Chapter 1

Chinese Medicine Unbound

Global phenomena are not unrelated to social and cultural problems. But they have a distinctive capacity for decontextualization and recontextualization, abstractability and movement, across diverse social and cultural situations and spheres of life. Global forms are able to assimilate themselves to new environments, to code heterogeneous contexts and objects in terms that are amenable to control and valuation. At the same time, the conditions of possibility of this movement are complex. Global forms are limited or delimited by specific technical infrastructures, administrative apparatuses, or value regimes, not by the vagaries of a social or cultural field.

—Aihwa Ong and Stephen Collier, Global Assemblages

Introduction

Separated from peninsular Malaysia by the narrow Johor Strait, the Republic of Singapore consists of one relatively larger (682 square kilometers), diamond-shaped main island and sixty-three mostly uninhabited islets, positioned at the southern end of the Strait of Malacca (which flows between peninsular Malaysia and Sumatra). The overwhelming majority of Singapore’s population of 5.47 million people (3.87 million citizens and permanent residents plus 1.6 million nonresidents, as of June 2014) reside on the main island, making Singapore one of the most densely populated cities in the world (National Population and Talent Division 2014). Linking the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean, the Strait of Malacca was an integral part of the ancient maritime Silk Routes, connecting various trading empires in the region, as well as facilitating the circulation of goods between East and South Asia, and then onward to Europe and back again. By no means restricted to historical records, the Strait of Malacca is still one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes and is likely to play an important role in China’s 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, part of President Xi Jinping’s One Belt, One Road Initiative (also known as the Belt and Road Initiative).1

The Port of Temasek, as Singapore was initially named by Javanese traders, was established sometime between the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, in service to the larger Malay trading world (under rule of the Malacca Sultanate) that ranged from the Johor River to the Riau Islands during the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries.2 Folklore associated with this trading empire also accounts for Singapore’s current appellation: supposedly on visiting the island, a Sumatran prince saw what he took to be a lion and renamed the island Singapura (or lion city). While indigenous Malays were the primary occupants when Sir Stamford Raffles claimed it as a free port under the auspices of the British East India Company in 1819, Chinese traders had also long maintained activity in the area. A mere thirty years later, ethnic Chinese laborers, merchants, and entrepreneurs constituted the majority of the island’s population (Kwa 1999).

This ethnic Chinese majority was subsequently maintained: as of 2014, Singapore’s ethnic composition was at a stable 76.2 percent Chinese, 15 percent Malay, 7.4 percent Indian, and 1.4 percent other (National Population and Talent Division 2014). Around the time of my fieldwork (2006 and 2007), Buddhism was the dominant religion (42.5 percent), followed by Christianity, Islam, and free thinker (approximately 15 percent each), Daoism (8.5 percent), and Hinduism (4 percent) (Lim et al. 2005: 19). To some extent, then, Singapore stands out for its clear and, some argue, carefully maintained ethnic Chinese majority. This demographic feature, however, should not minimalize the nation’s ethnic, religious, and linguistic diversity—a key issue in both colonial administration and post-colonial political rhetoric. Furthermore, as I will discuss in chapter 2, the political management of “race” and cultural heritage has impacted the practice and perception of Chinese medicine in Singapore.

Singaporean Chinese often explained to me that their forebears emigrated from China in search of a better life for themselves and their families. Once settled in the colonial Straits Settlements, overseas Chinese merchants and entrepreneurs enjoyed a substantial economic advantage over other ethnic groups due to colonialists’ preferential treatment, as I will describe further in chapter 2. Although post-colonial development encouraged a productive, docile consumer society, by the 1980s social critics and politicians alike attempted to combat what they labeled as Western (materialistic) values, perhaps to no avail. By the end of the twentieth century, career and salary were inextricably bound with certain forms of status in Singapore. Popularly referred to as the five C’s, the majority of Singaporeans with whom I spoke associated success with cash, cars, credit cards, condominiums, and country club memberships. Even the Singaporean government’s social architect Goh Keng Swee lamented, “The prevailing practice is to judge a man’s worth by his bank balance” (cited in Kwok 1999: 67).3

Although Goh was referring to the lower salaries and status of teachers at the time, Chinese medical professionals confronted the same dynamic at the time of my fieldwork. Simply put, Chinese medical physicians did not enjoy nearly the same privileges and status in Singapore as biomedical physicians because they did not practice biomedicine and were not, consequently, considered to be doctors. Although from the perspective of patients, Chinese medical physicians were doctors—and were referred to as such in English, Mandarin (yisheng) or Southern Chinese dialects like Hokkien (sinseh)—they were nonetheless marginalized in economic and political terms as “practitioners” (e.g., by the TCM Practitioners Act passed in 2000 and implemented in 2001).

Setting aside the political construction of multiracialism and ethnicity for a moment, this chapter will introduce one of the key problematics of the book: the manner in which Chinese medicine has been framed and negotiated in relation to both biomedicine and Singapore’s ethnic Chinese majority. I will begin with an autoethnographic vignette that illustrates the embedment of Chinese medicine in Singaporean life, particularly when used to ameliorate common everyday and seasonal conditions. I will then discuss the contemporary popularity and status of Chinese medicine in Singapore more broadly, as well as its political positioning as CAM. However persuasive or useful the CAM framework might be, I will argue, it does not adequately reflect the rich history, cultural relevance, or transnational flows associated with Chinese medicine. I will therefore reframe the discussion with respect to efforts to professionalize Chinese medicine in Singapore, the (re)invention of TCM in the PRC, and scholarly accounts of TCM’s contemporary globalization. These perspectives will link the specificities of my fieldwork with deeper and more-expansive flows and transformations, and thus suggest a broader relevance for the ethnographic descriptions of Chinese medicine in Singapore that follow.

Medicine In and Of Everyday Life

According to the National Environmental Agency (NEA 2009), the primary seasonal changes in Singapore are between monsoon and inter-monsoon seasons—marked by changes in wind, rather than by distinct wet and dry seasons. On average, rainfall begins to increase in October, peaks in December, and drops to a relatively dry period from February to early March. May, June, and July are meteorologically described as Southwest Monsoon season and are characterized by southerly or southeasterly winds, relatively less rain, and occasional Sumatra Squalls—thunderstorms that develop over Sumatra, Indonesia and travel eastward to peninsular Malaysia and Singapore, bringing one- to two-hour bursts of rain and sometimes strong winds. The coolest month of the year—and peak of the wet season—is December (calculated by averaging the daily mean temperature for each month between 1982 and 2008) at 26.4 degrees C (79.5 degrees F), with a gradual increase in mean temperature until reaching 28.3 degrees C (82.9 degrees F) in May and June; afternoons during inter-monsoon periods frequently reach temperatures above 32 degrees C (89.6 degrees F). Singaporeans with whom I interacted, however, rarely defined the summer in such formal terms.

A facetious expression that I heard on numerous occasions during my fieldwork claimed, “Singapore has three seasons: rainy season, dry season, and shopping season.” Although in practice Singaporeans shop year-round—for subsistence, recreation, or retail therapy—the end of May until the end of July is a specially designated, official shopping season that coincides with the Great Singapore Sale. The Singapore Tourism Board and the Singapore Retailers Association initiated this event in 1994 with a S$3 million advertising budget targeting Southeast Asia and Australia. Another, less-publicized shopping season also extends from mid-December until the end of Chinese New Year (usually mid-February), when Singaporean Chinese spend much more money than typical on luxury goods, gifts, and festival commodities. This shopping, however, is usually justified in terms of Chinese culture and heritage and activities are associated with festival season, whereas the Great Singapore Sale is intended to stimulate tourism and shopping for its own sake. In as much as Singaporeans spoke of a summer in the first place it therefore tended to be associated with the hot, relatively dry weather in May, June, and July, extending through the Southwest Monsoon and shopping season.

During this time of year, it was not uncommon to hear people complain of “summerheat” or “summerheat heatiness” (shure)— a seasonal form of heatiness (discussed further in chapter 5) that was often treated outside clinical settings by means of liangcha (cooling tea). Home-based remedies were an extremely common strategy for managing the embodied experience of Singapore’s climate, and were often the first step taken in health management. This was particularly the case when the condition occurred on a regular or seasonal basis, as was true in the following instance detailed in an excerpt from my field notes (dated July 2, 2007):

It’s just after 6A.M. and I am sweating already. Just the effort of showering and dressing outside the path of a fan has produced a fine film over my forehead. I choose the lightest and loosest clothes in my wardrobe in anticipation of the long, hot day ahead. By the time I descend the escalator onto the Sengkang MRT platform (a seven-minute walk from home), my shirt is beginning to stick to my back and the frizzy little hairs at my hairline have staged a revolution against conformity with the bun on the back of my head. June was hot—July is almost unbearable. Singaporean summers feel only a shade away from Hades, especially once the “haze” begins.4 Being very hard to ignore, the weather seems to loom large in the consciousness of many Singaporeans at this time of year, becoming the scapegoat for the ills of life. Over the last week or so, I have been suffering from an odd cough—it began very shallow and dry but within a few days moved deeper and became phlegmy. Nearly everyone with whom I’ve spoken about it has attributed it to the weather, and has given some recommendation for cooling.

Tim, manager of the Toa Payoh branch of Hock Hua—the Chinese food/medicine shop at which I observed—recommended I drink water and liangcha (especially the Buddha’s disciple fruit variety). He also kindly provided me with small bags of powdered herbs, carefully measured from bottles stored near the liangcha cart at the front of the store (incidentally, the same brand used by Dr Wang at his private clinic in Chinatown), intended to reduce heat, phlegm, and coughing. A colleague at the early childhood development center where I worked recommended water, liangcha, and starfruit (which is considered cooling) as well as rest and reduced talking. Another friend suggested drinking water and liangcha, adding salt to any beer I drank, and avoiding heaty foods like peanuts.

Although my cough gradually went away, by the end of August I developed symptoms of shure: mucous in my sinuses, a sore throat, and general weariness and disorientation, progressing to frequent and uncomfortable urination, an unquenchable thirst, and finally culminating in the telltale sign of small amounts of blood in my urine. After discussing these symptoms with my friends Adelle and Tom, I was assured that these experiences were extremely common at this time of year (particularly among women) and was encouraged to simply go to a Chinese medical hall—another term for Chinese pharmacies or food/medicine shops. They were aware of the most likely biomedical diagnosis (urinary tract infection) but saw little need for the use of pharmaceuticals for this condition. These pharmaceuticals were often considered, on the one hand, to be much weaker in Singapore than in many other countries and, on the other, to be toxic by comparison with the tonic qualities of Chinese medicine. “Waste your money for what, lah?!” Adelle demanded, after reporting that she successfully treated the same symptoms at approximately the same time every year with Chinese herbal remedies.5 Reassured by my already regular purchases of liangcha—particularly chrysanthemum and luohanguo (Buddha’s disciple/Arhat fruit, Siraitia grosvenorii)—I felt relatively confident following my friends’ advice.

I was most familiar with juhua (chrysanthemum, Chrysanthemum morifolium) and luohanguo liangcha, in which the primary herbs were steeped or briefly simmered in boiling water—sometimes along with other herbs like goujizi (wolfberries, Lycium chinense, Fructus Lychii) or jinyinhua (honeysuckle flowers, Lonicera japonica)—with rock sugar added to produce a sweetened beverage. These decoctions were considered mild remedies or simply pleasant beverages that one could drink as often as desired. Luohanguo—the fruit of a perennial vine indigenous to Guangxi province in southern China—produced a sweet, dark brown drink that was also often recommended for respiratory ailments, consistent with its use in the PRC (Hu 2005: 218–220).6 Although these grayish-brown dried fruits could be purchased whole from shops like Hock Hua, either singly or in packaged herbal combinations, people often purchased premade drinks for convenience. Several varieties of dried chrysanthemum were available for sale in food and medicine shops, medical halls, and grocery stores across the island packaged in plastic bags or paper-wrapped bricks. Although the flowers of this species can be found in many colors, sizes, and shapes depending on the variety cultivated (Hu 2005: 723), yellow and white dried flowers were most commonly sold in Singapore.

Figure 1.1. Luohanguo

While chrysanthemum and Buddha’s disciple fruit teas were consumed in cases of minor heatiness symptoms, lingyangsi (shaved antelope horn) was commonly cited for more-severe symptoms.7 The typical name of this herb8 is actually lingyangjiao (Cornu Antelopis): lingyang means antelope and jiao means horn. The use of si here instead, which could be translated as silk, fine, or thread-like, refers to a processing technique that involves thinly shaving the horn (in this case jiao is implied by the presence of si and is therefore omitted). Food and medicine shops like Hock Hua sold small bottles of these shavings for home preparation. While observing at Hock Hua in Toa Payoh, I noticed that the display on which these bottles were placed was frequently scrutinized by shoppers, who would occasionally engage a salesperson for information on the different grades available. However, I more commonly observed people buying the premade bottles of lingyangsi cha (antelope horn tea) from the liangcha cart at the front of the store than the materials with which to make it themselves. Like many Singaporeans opting for convenience, I decided to inquire at the Hock Hua branch closest to my apartment in Sengkang about what kind of liangcha might be appropriate for summerheat.

Hock ...