![]()

1

Liberation

Battles after the War

At the end of the war in 1945, Sara Kay, a teenager, came out of hiding in Lublin, Poland, and immediately made her way to her hometown in search of family. She reflected on her feelings soon after she was free: “Here I am waiting to be liberated and everything is gone and I’m liberated for nothing. I thought then everything will be good again. . . . I thought I’d go to school and I’d have my parents and I’d have my sister. I didn’t realize that it’s never going be like it was before the war.”1 For many children like Sara who had held onto hopes during the war that they would find their family alive in peacetime, it would be years before they would know stability, let alone tranquility. Indeed, this period was often the beginning of unwelcome new battles. There were those who found vestiges of family while others confronted the absolute losses hidden from them during the war. Some, usually younger children, were taken from familiar foster families and returned to familial strangers. These processes were fraught; displacement and changes were common; disappointments and despair were rampant.

At the same time, to the larger world, the few surviving children took on symbolic proportions. They represented the very hope of a future for the Jewish people. The end of the war pushed the adult Jewish and gentile community to move quickly on behalf of children.2 Different groups clamored over them as the children struggled with the consequences of “liberation.” Despite the political reality of immigration quotas, adult survivors had some agency in their lives. But children—especially younger ones—often had little voice in their postwar direction. Children had to be identified, and at the same time, they needed housing and maintenance until parents, old or new, could be found. These events occurred at parallel and overlapping times in the chaos of postwar Europe.

The reclamation of this tiny but all-important group would soon evoke profound sympathy but also long simmering tension between different ideological groups in the larger Jewish community. This was especially, but not exclusively so with orphans, for whom Jewish groups vied for control. Would they become new Jews to fulfill the dream of a national homeland in Eretz Yisrael?3 Devout Jews to replace the holy martyrs who had died “al Kiddush Hashem” (for the sanctification of God’s name)? Secular Jews to reinvigorate the remnant of European Jewry? Or simply children who had relatives who wanted them back? The children themselves were sometimes at odds with what others, including their own parents, saw as the best vision of a Jewish future. What was the answer? Addressing these questions, especially through the children’s voices, throws a bright light on the intersection of conflicting agendas immediately after “liberation” and highlights the external as well as the internal battles in the lives of the youngest remnant.

Examining the experiences of child survivors through their own memories illuminates the numerous, often unpredictable factors at play in the context of the larger postwar chaos, and also the children’s perspectives on efforts by the larger Jewish community to help them. Although individual stories are unique, the selections in this chapter reflect overall patterns that reoccur in multiple sources such as archival documents and survivor testimonies. Individual stories represent the different geographical locations discussed in the introduction’s demographic description, and further explicate the contributing and complicating effects of space and time on children’s stories. Finally, the accounts in this chapter focus on the children who, through a variety of reasons, were destined, not for Palestine or Canada or South America, but the United States.

Finding Children/Reclaiming Children

In the first instance, children had to be located, reclaimed, and then—depending on age—placed in children’s homes if orphaned or until surviving parents or other relatives came for them. To recover children, adults—parents, relatives, and Jewish organizations—found and created opportunities both formal and informal, above the law and illegal, intentional and accidental through which reconnections were sought, all amid the postwar disarray. Children did their part, too. As had happened during the war, afterward many initially used word-of-mouth to locate their kin. They simply asked other survivors. Ten-year-old Kaja Finkler, for example, recalls rushing toward a group of newly arrived Jews in Bergen-Belsen shortly after she was liberated there, asking if any had crossed paths with her mother.4 No one had. But Jack Arnel (né Jascha Aronowitz) still remembers with wonder the conversation in the Feldafing DP camp when he met a newcomer accidently. “What’s your name?” the man inquired of the fifteen-year-old. “Jascha Aronowitz of Vilna,” the teen replied. “Did you have a mother by the name of Chaya and a sister by the name of Sonia?” the stranger asked Jascha. And then he added, “Did you know they’re alive?” The teenager learned they were living in Łódź , Poland. Before long, the three were reunited and, four years later, arrived in New York.5 One sixteen-year-old girl vividly remembers the constant questions in another DP camp. “Where were you? Who do you see? Who died, and who do you know where they was [sic] left? . . . That was the only questions that were able to ask,” she states.6

Survivors kept their eyes open and their ears to the ground seeking any scrap of evidence that might reunite the remaining members of their families. Thousands of testimonies echo the immediate rush to establish knowledge and whereabouts of family members after the war. Oral inquiries were quickly supplemented with information from ubiquitous lists of names seemingly posted everywhere surviving Jews congregated, from DP camps to the hometowns where they returned, assuming family—if alive—would do the same.

The primary search by older children was for parents or siblings, if their fates were unknown. Though it confirmed that they were not alone in the world, other reunions were often temporary, especially if the children were teens. Bondi Horstein, cousin of sixteen-year-old Auschwitz survivors Elly Gross and Yboia Farkas, saw the girls’ names on a list posted at Hillersleben, a DP camp. He managed to find them, but the pair soon left him there for their former home, hoping to find their parents. After an arduous trip from Germany through Hungary and Czechoslovakia, they arrived in Romania. Elly remembers getting off the train and eagerly running to her home because “I was sure my mother, my father, my brother will be there.” But as echoed in so many recollections, “strangers were living in the house and there was nobody waiting for me.”7 Still, she remained until some years later, when many Jews left and Elly finally settled in New York.

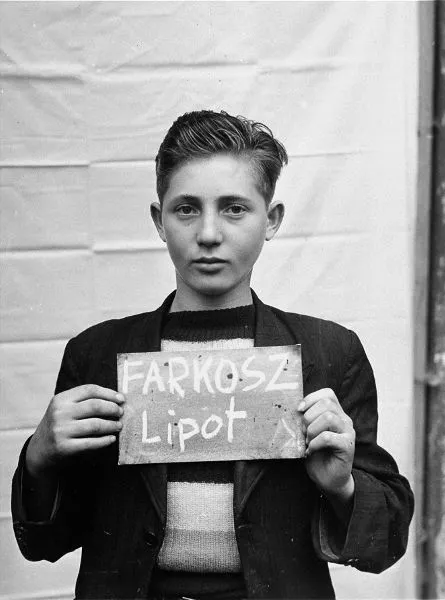

Sometimes, those caring for children in DP camps would circulate their photographs.8 Such was the case with seventeen-year-old Lipot Farkosz (fig. 1).9 He and his brother, Erwin, survived Auschwitz. After the war, the pair passed through Kloster Insdorf DP camp where their images soon joined the growing pool of photographs taken by adults in the camp with the goal of locating the children’s family members.10 Others turned to the DP press. One mother in Bergen-Belsen placed an ad with a picture of her child in the Landsberg DP camp’s newspaper seeking information about her young daughter, Estusia Haberman, “born in Lodz deported to Auschwitz in 1944.”11

Two important agencies, founded during the war particularly to locate missing persons, played an essential role in the postwar tracing services. The Central Location Index, Inc. (CLI), founded in New York in 1944 by the National Council of Jewish Women, was based in America. It had at least eight member organizations—Jewish and Christian—with which it exchanged information.12 Immediately after the war, it offered its services. In June 1945, the Cleveland Jewish News ran an announcement that there would soon be a local clearing house set up to provide forms to be filled out by community members searching for European relatives.13 There was similar activity around the country.

The Red Cross’s International Tracing Service (ITS), located in Germany, was the other main agency that focused on the reunification of families, including finding children.14 The enormous effort of the ITS is reflected in its vast archive today, which includes a Kindersucharchiv of 250,000 files of parents seeking children and children who were found without parents.15 Sometimes these organizations’ efforts yielded results.

Lithuanian-born Shaya (Sol) Lurie is an example of one child survivor who, through the ITS, was united with his American relatives. Under the auspices of Oeuvres de Secours aux Enfants (OSE), his postwar path took him from Buchenwald to France.16 There in a children’s home he remembers “a man that came from the Red Cross; he’s the one that asked if anybody has family in New York—in America, period.” Shaya knew that he did have aunts and uncles and cousins. He gave the man his family’s names. As was procedure, the Red Cross placed an ad in the US newspapers and one of Sol’s New York cousins noticed his name. She didn’t know whether or not they were relations but she wrote to him for details. And, he remembers, finally, “I gave her the right answers and it was my—my mishpocheh—my family.”17

Seventeen-year-old Jacques Ribons knew his parents were dead and one brother was alive but had no idea where—or even who—his US kin were. The Polish-born boy was liberated in Buchenwald with his brother, and like Shaya was soon sent to a home for boys in France. While there, he received a letter from a man in New Jersey who was in the habit of reading the Yiddish daily Forverts and saw the two names listed. He immediately wrote to Jacques, asking about his mother’s name and if they might be related. “Yes,” confirmed Jacques, “we’re your sister’s sons.” Initially unsure of their plans, once contact with their uncle was established, the boys decided. In 1947, the siblings arrived in New York.18

Romanian-born Bella Pasternak was sixteen and alone in Estonia by the time she made her way to a DP camp in Innsbruck, Austria. She remembers “by the kitchen there was a big board that everybody was—was able to write down for who they are looking and from where they coming, and anybody what group they are looking.” She was old enough to remember her US relatives’ name but not their address. Bella posted: “I am looking for the Weinstein family in America if anybody knows where they are located.”19 It worked. With the help of a tracing service that collected her information, she and her American relatives found each other. In 1946, Bella went to live with them in New York.

A tracing service and a surviving relative together determined Pearl’s destination. Her experiences demonstrate the role of Jewish organizations in locating relatives as well as hopes and disappointments of reunions.20 Pearl and her cousin spent the war years in a Belgian convent. One day after liberation the girls were told that a mother had come to get them. Pearl soon saw, much to her grief, that it was her cousin’s mother, not her own. Though the thirteen-year-old hoped her aunt would claim her, too, the woman, an Auschwitz survivor, felt unable to. Pearl recalls, “Eventually she was able to take her daughter back with her . . . she had one little room. . . . This is what always hurt me that she didn’t take me as well, she only took her daughter.” Her pain was compounded when she soon learned “my uncle came back [too] and I said, ‘This is the injustice of the world. How could both of them come back and not one of my parents or other aunts or uncles come back?’” Pearl’s aunt felt some responsibility toward her niece: she reported the girl to the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, which through their tracing department helped the child connect with her maternal uncle who had immigrated to America years before World War II. As a result, Pearl arrived in the United States in 1949 and settled in New York.21

Most often, it was the European survivors who initiated the search for relatives. Such is the case with Tama Huchman and her mother. She was eight years old when the war ended. Tama and her mother had survived together first in Poland in the Mylnów ghetto and then in farms, fields, and forests. After the war ended, they made their way to a DP camp in Pöcking, Germany, hoping to get to Palestine. Her mother was the youngest of thirteen children, most of whom had immigrated to the United States many years earlier. Tama states they went to a local office that helped DPs place ads in American Jewish newspapers. Her mother gave the official a detailed list of her relatives. They heard nothing. Just as they were about to leave for Palestine, a telegram arrived from a cousin in Indiana who had seen the ad and recognized her own and others’ names in the long list. Tama remembers learning that their US family had conferred and sent off their message. “We have your name, we’re getting papers, we’re bringing you to America,” she was told the relatives declared. Tama and her mother felt it was a chance of a lifetime. “We were going to the goldene medina,” she affirmed. They arrived in New York in October 1949 and from there went to her mother’s brother in Portland, Maine.22

There were non-refugee organizations that played a role, too, and not only in America. The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), for example, offered its support with a radio program that announced the names of children who were alone and might have UK relatives.23 Beginning with the words “Captive Children, An Appeal from Germany,” the announcer informed listeners about twelve children including “Jacob Bresler, a 16-year-old Polish boy, has survived five concentration camps, but has lost his entire family. . . . Sala Landowicz, a 16-year-old Polish girl, who’s in good health after surviving three concentration camps. . . .”24

One letter from the Central Location Index highlights the fact that its work began after the war but continued well beyond its immediate aftermath. Etta Deustch, executive director of the CLI, wrote to the ITS, the Central Committee of Liberated Jews, and the Joint Distribution Committee, Warsaw, in 1948, wondering whether one Sara Dank, age fifteen, might be related to three children with the same surname, all in Poland. If so, “perhaps they are not yet in contact with each other,” she wrote. “Please investigate this case and inform us of the outcome.” In addition, Deutsch offered her own agency’s services. “If these children are interested in locating relatives in the USA,” she continued, “please send us the case and we will service it.”25 Deutsch’s inquiry suggests that, more than three years after the war, there was still much work to be done helping children find relatives.

All of these efforts were laudable and piqued both interest and hopes. Some indeed yielded results. But, given the death toll of Jewish youth, the majority of attempts to find children—like Mrs. Haberman searching for her daughter, Eustusia—would end in utter despair.

Detours: Circuitous Paths in the Immediate Postwar Months

At the...