![]()

P

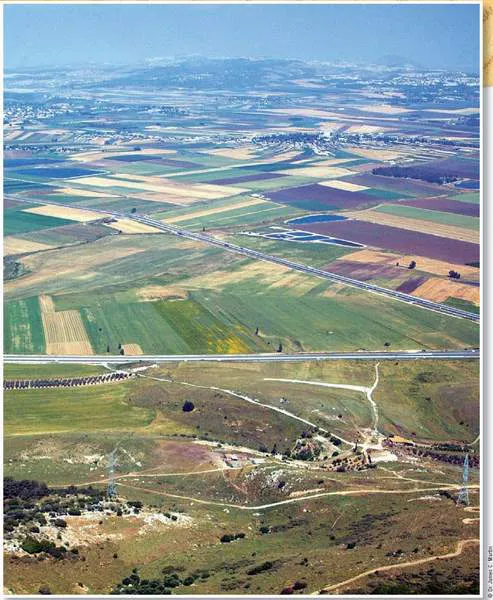

Aerial view of the Jezreel Valley looking N toward the western section of the Nazareth Ridge. This area provided an important transportation route across ancient Palestine.

P (Priestly). An abbreviation used (along with D, E, and J) to designate one of the supposed sources of the PENTATEUCH, according to the Documentary Hypothesis. This priestly document is dated after the EXILE, when the professional priesthood is thought to have elaborated ritual practices and made them binding upon all the Jews. See also PRIESTS AND LEVITES.

S. BARABAS

Paaneah pay’uh-nee’uh. See ZAPHENATH-PANEAH.

Paarai pay’uh-ri (

H7197, apparently from

H7196, “to open [the mouth wide]”). An A

RBITE, listed among D

AVID’s mighty warriors (2 Sam. 23:35); in the parallel passage he is called “Naarai son of Ezbai” (1 Chr. 11:37). See discussion under E

ZBAI.

Pacatania pak’uh-tan’ee-uh. See PACATIANA.

Pacatiana pak’uh-ti-ay’nuh (

, “peaceful”). Sometimes Pacatania. A province in A

SIA M

INOR whose capital was L

AODICEA. At the end of the 3rd cent. A.D., the province of A

SIA was divided into seven parts, two of which were P

HRYGIA Prima on the W and Phrygia Secunda on the E. After the time of the Emperor Constantine, Phrygia Prima also bore the name Pacatiana (Secunda was also known as Salutaris; cf. W. Smith,

Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography, 2 vols. [1857], 2:624-25; W. M. Ramsay in

HDB, 3:865). At the end of 1 Timothy, the KJV includes this subscription on the margin: “The first to Timothy was written from Laodicea, which is the chiefest city of Phrygia Pacatiana

[mētropolis Phrygias tēs Pakatianēs].” This is the reading of the TR and of most Greek

MSS, but none earlier than the 8th cent.

R. L. ALDEN

Pachon pay’kuhn (II

). Ninth month of the Egyptian year, approximately June (3 Macc. 6:38). See E

PEIPH.

Paddan, Paddan Aram pad’uhn, pad uhn-air’uhm (

H7019 [only Gen. 48:7], prob. “plain”;

H7020 [cf.

, “field/land of Aram,” Hos. 12:12, MT v. 13]). KJV Padan, Padan-aram. The area of Upper M

ESOPOTAMIA around H

ARAN, upstream of the junction of the rivers E

UPHRATES and H

ABOR (Gen. 25:20; 28:2-7; 31:18; et al.). The name occurs only in Genesis and is thought to be equivalent to A

RAM N

AHARAIM (but see

ABD, 5:55). The strategic importance of this sector of the F

ERTILE C

RESCENT is reflected in the patriar chal narratives. Here A

BRAHAM dwelt before his emigration to Canaan. He sent his servant to it to procure a bride for his son, I

SAAC. And to the same area J

ACOB fled and dwelt with L

ABAN. See also A

RAM (

COUNTRY).

J. M. HOUSTON

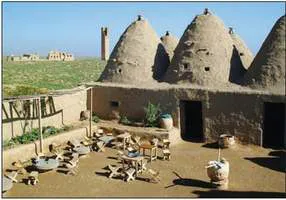

The Plain of Haran, where this photo of an old beehive home was taken, is in the region that the Bible calls Paddan Aram.

paddle. This word, which in Middle English referred specifically to a spade-shaped tool used for cleaning a plow, is used once by the KJV to render yātēd H3845 (Deut. 23:13). The Hebrew term means “peg” but has a variety of uses. In this passage it refers to a wooden spade to be used for latrine purposes (RSV, “stick”; NRSV, “trowel”; NIV, “something to dig with”).

Padon pay’duhn (

H7013, “ransom,” possibly the short form of a theophoric name such as

H7016, “Yahweh has redeemed”). Ancestor of a family of temple servants (N

ETHINIM) who returned from the

EXILE with Z

ERUBBABEL (Ezra 2:44; Neh. 7:47; 1 Esd. 5:29 [KJV, “Phaleas”]).

pagan. See GENTILE.

Pagiel pay’gee-uhl (

H7005, perhaps “one who intercedes with God” or “God has entreated

[or met]”). Son of Ocran; he was the leader from the tribe of A

SHER, heading a division of 41,500 (Num. 2:27-28; 10:26). Pagiel was among those who assisted M

OSES in taking a census of the Israelites (1:13) and who brought offerings to the Lord for the dedication of the

TABERNACLE (7:72-77).

Pahath-Moab pay’hath-moh’ab (

H7075, “governor of Moab”). This name (apparently derived from a title) is attributed to an Israelite who may have held some office in M

OAB, perhaps at the time that D

AVID subjugated that nation (cf. 2 Sam. 8:2). We know nothing about him, but he had more than 2,800 descendants (through two distinct lines, it seems) who returned from the

EXILE under Z

ERUBBABEL (Ezra 2:6; Neh. 7:11; 1 Esd. 5:11 [KJV, “Phaath Moab”]). Another group of 200 of his descendants returned later with E

ZRA (Ezra 8:4; 1 Esd. 8:31). Eight of them are listed as having married foreign wives (Ezra 10:30), and at least one of them, H

ASSHUB, helped N

EHEMIAH rebuild the wall of Jerusalem (Neh. 3:11). His name—referring possibly to the chief of his clan—is listed among “the leaders of the people” who signed the covenant of Nehemiah (Neh. 10:14).

R. L. ALDEN

Pahlavi pah’luh-vee. Also Pehlevi. This term was applied by the Persians to that dialect of their language that was used by the Sassanian dynasty from the 3rd to the 7th cent. A.D. (i.e., from the overthrow of the PARTHIANS to the time of the Muslim conquest). See PERSIA. The Pahlavi script (derived from a late form of the Aramaic or Syriac ALPHABET) was used also to put down in written form a much earlier stage of the language known as Avestan, but preserved only in oral form from the period of Zoroaster (see ZOROASTRIANISM). The Zoroastrian Scriptures, known as the Avesta, survived by oral tradition from the 6th cent. B.C. until the 7th cent. A.D., and then began to achieve written form, doubtless in answer to the challenge of the written Koran of the Muslims. The earliest datable inscriptions, however, in Arsacid or Parthian Pahlavi appeared on the coins of Vologases I (A.D. 51-79; cf. R. Ghirshman, Iran [1954], 256-57); previously, the Parthian coins had borne Greek inscriptions exclusively.

The language came into its own as the official medium of communication only with the rise of the Sassanian dynasty under Ardashir I (c. A.D. 224), and so remained until they were finally overwhelmed by the Muslims in 651. Unfortunately, however, there was little of the literary Pahlavi that survived destruction, although portions of the Dadhastan i Menoghkhrad (“Doctrine of Celestial Wisdom”) and the Ardagh Viraz-Namagh (“Vision of Ardagh Viraz”) contain material on Zoroastrian theology that is thought to go back to the period of Khosrau I (531-579). Likewise the legendary life of Ardashir I in Karnamak-i Ardashir-i Papakan has been shown to be current in the late Sassanian period before the Muslim conquest. Quite possibly the important later compilation known as the Denkard, which deals with matters of cosmology and religious legends of various sorts, contains historical references to Shapur I (241 –270) as a patron of literature, who encouraged the translated of major works in Greek and Sanskrit into the Pahlavi language.

Certain major difficulties have beset the study of Pahlavi literature, the chief of which is the habit of the scribes in regard to the use of ARAMAIC expressions and terms, which they employed in preference to the actual Pahlavi words that they represented. The reason for this practice seems to have been (a) the prestige that the earlier language enjoyed throughout the Middle E, and (b) the words could be written more briefly in Aramaic than in the more polysyllabic Pahlavi. It was formerly supposed by modern scholars that the language had actually absorbed these Aramaic terms into their actual speech (just as Persian later absorbed a very high percentage of Arabic). A glossary has been preserved, the Frahang-i-Pahlavik, which lists these Aramaic words with their Pahlavi equivalents, and the Pāzand texts of Zoroastrian religious books followed a policy of replacing the Aramaic terms with Persian equivalents equipped with vowels. These serve to indicate the way by which the Pahlavi texts actually were read aloud (e.g., the preposition “from” was written with Aram. min, but read aloud as hac).

The second major difficulty in the interpretation of Pahlavi is that the various letters of their alphabet of 18 letters tended to develop forms so similar to each other as to be virtually indistinguishable except for the context. Students of the language, lacking for the most part any vowel notation, and coping with the similar-appearing consonants, find certainty of interpretation extremely difficult to attain. See also LANGUAGES OF THE ANE III.

(See further H. Nyberg, Hilfsbuch des Pahlavi, 2 vols. [1928-31]; J. C. Tavadia, Die mittelpersische Sprache und Literatur der Zarathustrier [1956]; R. C. Zaehner: The Teachings of the Magi: A Compendium of Zoroastrian Beliefs [1956]; D. N. MacKenzie, A Concise Pahlavi Dictionary [1971]; C. J. Brunner, A Syntax of Western Middle Iranian [1977]; R. Asha, The Persic (“Pahlavi”): A Grammatical Precis [1998].)

G. L. ARCHER

Pai pi. Alternate form of PAU.

paint. Biblical references to paint and painting are comparatively few, in spite of the fact that the people of the ANE have always been fond of bright colors. Black paint was used to enlarge the eyes (2 Ki. 9:30; Jer. 4:30; Ezek. 23:40). In Jer. 22:14, mention is made of painting a house in red; in Ezek. 23:14, of drawing pictures on the wall with the same pigment (the Hebrew word is šāšar H9266, referring prob. to the bright red pigment vermilion, either cinnabar, red mercuric sulphide, or minium, red oxide of lead).

Painting played a large part in the life of the ancients. It began with the decoration of pottery

Bathhouse at Masada with some of the paint on the walls still visible.

and of the body. The colors, taken from nature, usually had religious and magical meaning. There is hardly any information of the painter’s craft from MESOPOTAMIA. In EGYPT, however, most of the craftsmen seem to have done their own painting for centuries. Individual painters and even easel painting and its products can be traced as far back as 2600 B.C. A picture of an artist’s workshop dates to the Amarna period (R.J. Forbes, Studies in Ancient Technology, 9 vols. [1955-65], 3:241). The color schemes varied in different periods. Early wall paintings at Hierakonpolis show the use of yellow, red, green, white, and black. The ancients painted pottery, plaster, stone, wood, canvas, papyrus, ivory, and semiprecious stones or metals (ibid., 242). Fragments of paint have been found by archaeologists in houses from the period of the monarchy in Palestine (e.g., by W. F. Albright at Tell Beit Mirsim). See ARCHITECTURE.

P. A. VERHOEF

palace. The common Hebrew word bayit H1074, “house,” is often rendered “palace” in the NIV and other versions when it refers to the residence of a king or high official (Exod. 8:3 et al.; cf. also Gk. oikos G3875 in Matt. 11:8). More specific terms are Hebrew hêkāl H2121 (2 Ki. 20:18 and frequently) and bîtān H1131 (only Esth. 1:5; 7:7-8), as well as Greek aulē G885, “court, hall” (Matt. 26:3 et al.), basileios G994, “king’s dwelling” (Lk. 7:25), and praitōrion G4550, from Latin praetorium, “governor’s residence” (Jn. 18:28 et al.). For the historical development of the palace, see ARCHITECTURE.

One of the earliest palatial type structures was the “palace” of AI, about 22 ft. wide by 66 ft. long, with four interior pillars down the middle and a second story, a prebiblical Canaanite structure of the Early Bronze Period. At TAANAK from the Middle Bronze II Age was a palace about 66 ft. per side that included several rooms approximately 10 by 14 ft. with a large court occupying a corner of the plan. The “palace” at MEGIDDO (c. 1650-1150 B.C.) was named for its character and size. It extended through several levels with variations, indicating a prolonged era of power. A large structure discovered at Tell el-Ful (GIBEAH of Benjamin) may have been the palace of King SAUL (cf. A. Mazar, Archaeology of the Land of the Bible, 10,000-586 B.C.E [1992], 371-74).

SOLOMON’s palace, of which nothing remains and which may have been destroyed by SHISHAK as the Lord’s penalty for REHOBOAM’s apostasy, was called the House (Palace) of the Forest of Lebanon because its columns and roof structure were of Lebanon cedar (1 Ki. 7:2 et al.; see FOREST). It was built in close proximity to the TEMPLE on the S and measured 50 by 100 cubits. Near it was a porch leading to the throne room, which was connected to the temple enclosure by a single gate. The House had an enclosing wall of three courses of stone reinforced against earthquake shock by a row of wood beams. Valuable stones were used in the masonry work (7:9).

Later, OMRI and AHAB, kings of Israel, built their palaces at SAMARIA, the latter’s being distinguished by a large, enclosed court formed by a wall of casemate construction. Jeremiah makes several references to parts of the palace that was destroyed by NEBUCHADNEZZAR (Jer. 36:20, 22; 37:21; a guard room, 38:6). In NEHEMIAH’s time, wood beams were parcelled out on the king’s order (Neh. 2:8). The luxury and splendor of Persian palaces are detailed in Esth. 1, and they are amply verified from the excavations. For ornamentation and beauty, painted plaster was frequently employed in Babylonian palaces. Except for cut stone in the eras of Solomon and Ahab, general construction was of rubble stone and plaster finish.

The postexilic period presents a governor’s residence at Tell ed-Duweir (LACHISH) that featured an inner, enclosed court with rooms arranged on three sides, having several arched doors and vaulted roofs, and covered an area of c. 2,700 square yards. In TRANSJORDAN, Araq el-Amir presents on the outside a bare, flat wall of desert fortification enclosing soldier and living quarters within, from the end of the Ptolemaic age. ANTIOCHUS Epiph-anes is reported to have built a palace to the S of the temple in Jerusalem, but nothing remains of it.

The site of the Tower of HANANEL in Jerusalem was incorporated by HEROD the Great into his Tower of ANTONIA, a rectangular palace with four corner towers, and apartments between. It enclosed an open court that is the site of the present Sisters of Zion Convent, in whose basement may be seen the pavement of the court of Herod’s Tower of Antonia. Cisterns below the pavement are still used. Herod also built a fortress atop the table rock at MASADA, along the W shore of the Dead Sea. This fortress was of great beauty and included several fountains. Excavations have justified JOSEPHUS’s descriptions. It became the last holdout of the Jews against the Romans in A.D. 73 or 74.

In the NT, “the palace of the high priest” (Matt. 26:3; Jn. 18:15) refers to his offici...