![]()

PART 1

THE IRRESISTIBLE ADVANCE

![]()

1

THE EARLY CENTURIES: EVANGELIZING THE ROMAN EMPIRE

The world today—not just the Christian church—would be very different if the zeal to evangelize had not been at the very heart of the Christian faith. Christianity and missions are inseparably linked. It is impossible to imagine Christianity as a living religion today without the vibrant missionary outreach that sprang forth after Pentecost. This missionary vision was part and parcel of the life of the church. The New Testament writers were not religious thinkers who speculated on matters of doctrine. Rather, theology was born out of necessity—the necessity of preaching the gospel. The New Testament is the result of that passion. “The gospels in particular,” writes David Bosch, “are to be viewed not as writings produced by an historical impulse but as expressions of an ardent faith, written with the purpose of commending Jesus Christ to the Mediterranean world.”

It was the post-Pentecost generation that turned the world upside down—spreading Christianity beyond the borders of Palestine as far west as Rome and into virtually every major urban center in the entire eastern empire. “What began as a Jewish sect in A.D. 30,” writes missiologist-historian J. Herbert Kane, “had grown into a world religion by A.D. 60.” Inspired by the leadership of such great Christians as Peter and Paul, and driven abroad by persecution (and the destruction of the temple in Jerusalem in A.D. 70), many trained and lay evangelists spread out, bringing the message of Christ with them. “Every Christian,” writes Stephen Neill, “was a witness,” and “nothing is more notable than the anonymity of these early missionaries.”

Fortunately for these early missionaries, circumstances were almost ideal for spreading the faith. In comparison to later missionaries, who would often face almost impossible odds, these early evangelists worked within a system that often paved the way for their ministry. There was great opportunity for mobility within the Roman Empire in the centuries after Christ. The amazingly well-structured Roman roads were an open invitation for people to move about, and the relative peace that prevailed made travel even more appealing. Moreover, unlike most missionaries of later centuries, the early evangelists were not forced to endure years of grueling language study. Greek was the universal language of the empire, and Christians could communicate the gospel freely wherever they went.

Another factor paving the way for a public Christian witness was the availability of synagogues. The book of Acts mentions over and over again the preaching that occurred in Jewish synagogues—public forums that allowed Christian ideas to be disseminated throughout the empire for more than a generation following the death of Christ. Though persecution was an ever-present reality, there was room for public debate in Roman society. There was a spirit of openness to new ideas—“a shifting toward a rational and moralistic monotheism,” while at the same time a shifting away from “polytheistic religions with their capricious and malicious deities.”

Christianity stood out from other ancient religions in its exclusivist stance. While the knowledge of doctrine was often shallow for most new converts, there was no ambiguity about the uniqueness of the new religion. Christianity alone demanded that followers deny all gods but the one true God. The gospel “was presented in sharply yes-or-no, black-and-white, friend-or-foe terms. Urgency, evangelism, and the demand that the believer deny the title of god to all but one, made up the force that alternative beliefs could not match.” The growth of the new faith was remarkable: “on the order of half a million in each generation from the end of the first century up to the proclaiming of toleration.”

Christianity penetrated the Roman world through five main avenues: the preaching and teaching of evangelists, the personal witness of believers, acts of kindness and charity, the faith shown in persecution and death, and the intellectual reasoning of the early apologists.

From contemporary accounts we learn that the Christians of the early centuries were very eager to share their faith with others. When the synagogues closed their doors to them, teaching and preaching was done in private homes, usually by itinerant lay ministers. Eusebius of Caesarea tells of the dedication of some of these traveling evangelists in the early second century:

At that time many Christians felt their souls inspired by the holy word with a passionate desire for perfection. Their first action, in obedience to the instructions of the Saviour, was to sell their goods and to distribute them to the poor. Then, leaving their homes, they set out to fulfill the work of an evangelist, making it their ambition to preach the word of the faith to those who as yet had heard nothing of it, and to commit to them the book of the divine Gospels. They were content simply to lay the foundations of the faith among these foreign peoples: they then appointed other pastors and committed to them the responsibility for building up those whom they had merely brought to the faith. Then they passed on to other countries and nations with the grace and help of God.

Perhaps even more significant than the evangelism conducted by the traveling lay preachers was the informal testimony that went out through the everyday lives of the believers. “In that age every Christian was a missionary,” wrote John Foxe in his classic Book of Martyrs. “The soldier tried to win recruits …; the prisoner sought to bring his jailer to Christ; the slave girl whispered the gospel in the ears of her mistress; the young wife begged her husband to be baptized …; every one who had experienced the joys of believing tried to bring others to the faith.” Even the Christians’ harshest critics recognized their fervent evangelistic zeal. For example, Celsus’s description, though very biased, is telling:

Their aim is to convince only worthless and contemptible people, idiots, slaves, poor women, and children…. They would not dare to address an audience of intelligent men … but if they see a group of young people or slaves or rough folk, there they push themselves in and seek to win the admiration of the crowd. It is the same in private houses. We see wool-carders, cobblers, washermen, people of the utmost ignorance and lack of education.

As important as such witnessing was, the nonverbal testimony of Christian charity may have had an even greater impact. Christians were known by their love and concern for others, and again, some of the most telling evidence of this comes, not from the mouths of Christians themselves, but from the critics of Christianity. Emperor Julian was concerned that Christians not outshine those of his own religion. He was chagrined that Christianity had “advanced through the loving service rendered to strangers, and through their care for the burial of the dead.” He found it scandalous that the “godless Galileans care not only for their own poor but for ours as well; while those who belong to us look in vain for the help that we should render them.”

The testimony that the early Christians displayed in life was also evident in death. Until the fourth century, when Emperor Constantine publicly professed Christianity, persecution was a real threat for believers who openly confessed their faith. Though the total number of martyrs was not unusually high in proportion to the population, and though outbreaks of persecution occurred only sporadically and even then were generally local in nature, no Christian could ever feel entirely safe from official retribution. Beginning with the stoning of Stephen, they faced the grim reality that such might also be their fate—a sobering thought that served to exclude nominal Christians from their numbers. The fire of persecution purified the church, and the courage displayed by the innocent victims was a spectacle unbelievers could not fail to notice. There are many “well-authenticated cases of conversion of pagans,” writes Neill, “in the very moment of witnessing the condemnation and death of Christians.” The second-century apologist Tertullian perhaps said it best: “The blood of the martyrs is the seed of the church.”

While persecution and martyrdom drew many unbelievers to Christianity through their emotions, the reasoned and well-developed arguments of the early apologists won still others through their intellects. Christians, beginning with the apostle Paul in Athens, realized that this factor alone could be a drawing card in witnessing to the learned pagan philosophers. These defenders of the faith, including Origen, Tertullian, and Justin Martyr, had a powerful influence in making Christianity more reasonable to the educated, a number of whom were converted.

Even as the church was expanding through various means, however, it was facing setbacks as well. The very persecution that set the stage for testimonies of unbending faith also set the stage for denial of faith. This was the case in Asia Minor around A.D. 112. In a letter to Emperor Trajan, Pliny the Younger, who was then governor of Bithynia, outlined his actions against those people who were brought before him accused of being Christians. “So far this has been my procedure when people were charged before me with being Christians. I have asked the accused themselves if they were Christians; if they said ‘Yes,’ I asked them a second and third time, warning them of the penalty; if they persisted I ordered them to be led off to execution.”

Pliny did not specify the number of executions, but when threatened with death, many denied the faith and supported that denial by giving homage to the images of the emperor and the gods and cursing Christ. Indeed, the number that denied the faith was apparently far greater than the number who did not, because Pliny reported to the emperor that “the temples, which had been well-nigh abandoned, are beginning to be frequented again” and “fodder for the sacrificial animals, too, is beginning to find a sale again.” And he sums up his success by saying: “From all this it is easy to judge what a multitude of people can be reclaimed, if an opportunity is granted them to renounce Christianity.”

A similar outcome was reported in Alexandria in the mid-third century during the persecution under Emperor Decius. According to Eusebius, both women and men were brutally persecuted. Among them were Quinta, Apollonia, Metra, and Serapion, who endured terrible torture before they succumbed to death. “Much terror was now threatening us,” writes Eusebius, “so that, if it were possible, the very elect would stumble.”And some did stumble. They approached the pagan altars and “boldly asserted that they had never before been Christians.” Others, “after a few days imprisonment abjured”; and still others, “after enduring the torture for a time, at last renounced.”

Another factor that impeded the growth of the early church was doctrinal controversy. “The list of major Christian doctrinal controversies during the first five centuries is long,” writes Milton Rudnick. “Among the groups regarded as dangerously false were: Judaizers, Docetists, Gnostics, Marcionists, Montanists, Monarchians, Novationists, Donatists, Arians, Nestorians, and Monophysites.” Besides these groups there were factions within the church that fought over such things as the date of Easter and clerical appointments. “It is impossible to measure the negative impact of these controversies,” continues Rudnick. “In all likelihood it was considerable.”

But the vibrant evangelism that was conducted during the post-apostolic period began to wane in the early fourth century during the reign of Emperor Constantine. Christianity became a state religion, and as a result, the churches were flooded with nominal Christians who had less concern for spiritual matters than for political and social prestige. Christianity became the fashion. Elaborate structures replaced the simple house-churches, and creeds replaced the spontaneous testimonies and prayers. The need for aggressive evangelism seemed superfluous—at least within the civilized Roman world.

On the outskirts of the empire, however, barbarians threatened the very stability of the Roman state. The prospect of converting them to Christianity became a much-sought-after goal of government officials who strongly supported the work of aggressive evangelists such as Martin, Bishop of Tours. Martin was a fourth-century soldier who entered a monastery and went out from there spreading the gospel throughout the French countryside. Some of the earliest and most effective “foreign” missionaries, though, were not aligned in any way with the state or the church at Rome. Ulfilas (an Arian) and Patrick and Columba (both Celtics) had no direct ties with the Roman church or state (though their evangelistic efforts made certain areas of Europe more amenable to the Roman system). Their primary objective was evangelism, accompanied by spiritual growth—an objective that would often become secondary during the succeeding centuries.

Paul the Apostle

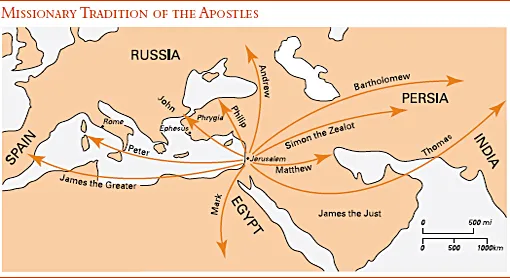

The starting point of Christian missions is, of course, the New Testament church. The frightened and doubting disciples who had fled during their master’s anguished hours on the cross were empowered with the Holy Spirit on the day of Pentecost, and the Christian missionary movement was born. The most detailed and accurate record of this new missionary outreach is contained in the book of Acts, where the apostle Paul stands out, while Peter, Barnabas, Silas, John Mark, Philip, Apollos, and others also play important roles. Apart from Scripture, however, little is known of these biblical figures. According to tradition, some time after the death and resurrection of Jesus, the disciples met in the “upper room” or the Mount of Olives (depending on the source), and there Peter or another disciple divided up the world among them for missionary outreach. By some accounts Matthew is said to have gone to Ethiopia, Andrew to Scythia, Bartholomew to Arabia and India, Thomas also to India, and the rest to other regions.

Most of these accounts, except for that of Thomas, have little or no historical support. As the story goes, Thomas disregarded the Lord’s call for him to take the gospel to the East—a defiance that resulted in his being carried off as a slave to India, where he was placed in charge of building a palace for King Gundaphorus. The tradition continues that, while under the king’s service, Thomas spent his time spreading the gospel rather than building the palace—an offense that quickly brought him a prison term. In the end, Thomas had the opportunity to share his faith with the king, who then became a believer himself and was baptized. Though many of the details of the story seem fanciful, the basic outline may have an element of truth. A group of “Thomas Christians” in south-west India still worship in an ancient church said to be founded by Thomas, and archaeological digs have now established that there actually was a King Gundobar who reigned in India during the first century.

Many historians discount this tradition as no more than legend, but the significance goes beyond the actual historicity of the stories themselves. The widely circulated tales of the apostles carrying the gospel to the very ends of the earth infused the early church with a missionary mind-set that has been passed down t...