- 332 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The author's purpose for Introduction to Old Testament Theology is to show how different approaches to the Old Testament can be brought together into a single theology. The author develops his own distinctive approach which he calls canonical theology.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Introduction to Old Testament Theology by John H. Sailhamer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Biblical Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

Biblical StudiesPART I

INTRODUCTION

ONE

INTRODUCTION

1.1. WHAT IS OLD TESTAMENT THEOLOGY?

Since not everyone is agreed on what Old Testament theology is or should be, we begin this work with an attempt to clarify for the reader our own understanding of its nature. The purpose of these introductory remarks, then, is to give a preliminary description of the task of OT theology. We do not mean to imply that our description is valid for all, but merely to set forth clearly the approach we will take.

As is clear from the name, OT theology is a certain kind of theology. It is the study of theology that has the Old Testament as its primary subject matter. It would seem that little else need be said since it is common knowledge what the Old Testament is and every reader of the Bible knows what theology is. But there are several questions that arise as soon as we begin to look more closely, even concerning the nature of theology itself.

There is diversity of opinion about how one’s understanding of the term theology is affected when it is applied to the Old Testament. Is it correct to say that “Old Testament theology” is merely that branch of theology that has the Old Testament as its subject matter? Does not the label “Old” have some effect on the sense of the term theology? Does not the idea of an Old Testament theology also suggest that there is a distinction between it and a New Testament theology? If so, then the sense of the term theology will not be the same in both cases.

For the sake of clarity in understanding the nature of OT theology, it is important to come to some agreement on the meaning of the term theology. Only then can we speak with confidence about the nature of OT theology. What, then, is theology?

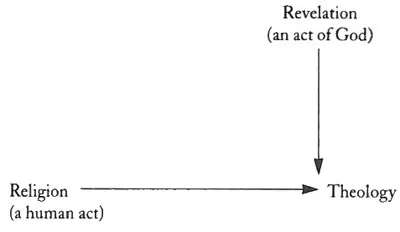

In discussions of OT theology, the term theology has generally been associated with two quite different concepts: divine revelation1 and religion. In one sense these two concepts, revelation and religion, may seem close in meaning. However, as the

Figure 1.1

words have been used in discussions of OT theology, they have each taken on a particular sense and have grown poles apart in meaning. We will have to examine each of these concepts more closely to see what is meant by each term and how each affects our understanding of the nature of theology.

The word “revelation” is usually taken as a term which describes an act of God.2 God, we say, has revealed himself in the Bible. On the other hand, “religion” is a term which describes an act of man.3 The relationship between the two terms can be demonstrated by saying humanity accepts God’s revelation and acts in accordance with it and that is called religion.4 The chart in Figure 1.1 shows how each of these concepts is related to the nature and task of theology.

When our understanding of the nature and purpose of theology is related to either of these two terms, it takes on a particular and distinct meaning. Since this meaning will carry over to our understanding of OT theology, we should look more closely at the two senses of theology which are related to these two terms.

1.1.1. Theology and Revelation

The German poet, Rainer Maria Rilke, has aptly expressed what the notion of theology means when it is linked to the concept of divine revelation:

Catch only what you’ve thrown yourself, all is mere skill and little gain; but when you’re suddenly the catcher of a ball thrown by an eternal partner…catching then becomes a power—not yours, a world’s.5

When one understands theology in relation to the concept of divine revelation, it is the study of what God has revealed about himself or about the world. It is, in Rilke’s words, a catching of “a ball thrown by an eternal partner.” As such it is a power not one’s own, but “a world’s.” It is in this sense that the task of theology has been classically understood. The late orthodox theologian David Hollaz, for example, defined theology as “God given” (habitus Theosdotos divinitus datus) because for him it was a “revealed theology” (theologia revelata): “With respect to its principle, revealed theology is called a God-given way of thinking (habitus); not as though it is immediately infused into one’s mind, but because its fundamental basis (principium) is not human reason but rather divine revelation. Therefore revealed theology is called wisdom coming from on high.”6 Conceived in this way, theology, being to some extent also a science, is an attempt to formulate God’s revelation into themes and propositions. It is the scientific explication of revelation. It works on the premise that God has revealed himself in ways that can be observed and restated in more or less precise language. The task of theology in this sense is the restatement of God’s self-revelation. To quote Rilke again, it is a “catching [that] then becomes a power.”

In connecting theology with revelation, it is important to note that theology, in this sense, is put in a direct relation to a special process that has been initiated by God.7 God has spoken and acted. God has revealed himself in observable and communicable ways. Theology’s task is to pick up the trail and pursue the line of discourse, taking its clues from God’s acts and words and translating their meaning to particular audiences and times.

It is easy to see that within such an understanding of the term, theology is given a high place among the sciences. Indeed, for many it is the “queen of the sciences.” Theology’s standing at one end of a process begun by God gives it not only a special rank, but also a unique authority. Theology can dare attempt to say, “Thus saith the Lord.” What other field of study would make such a claim? Theology cannot claim to speak with divine authority nor can it be equated with divine authority, but it can and must claim to speak on behalf of God’s revelation and hence expects its word to carry more than its own weight. Insofar as theology can rightly grasp God’s revelation and accurately translate it into a particular setting, theology can lay claim to be normative. It can expect to be taken as a standard by which to measure oneself against the Word of God.

When such an understanding of the term theology is given to the phrase Old Testament theology, it raises several questions. How, for example, can an Old Testament theology claim to be normative? Does not the notion of the term Old suggest that the value of this theology has passed and that it has been replaced by the New? Is it not a serious problem to label one Testament “Old” and the other “New” and then to hold them both as normative? How can both continue to be a standard of one’s understanding of God? If they are both the standard, in other words, why do we call the one “Old” and the other “New”? The problem we are raising here is not a new one, nor is it insoluble. It is, however, one that lies at the heart of every Christian’s attempt to understand OT theology.

An understanding of the term theology that sees its task as the restatement of God’s revelation and hence as normative, has far-reaching implications for one’s understanding and approach to OT theology. It will influence much of what is proposed for OT theology in this book. Not everyone, however, agrees that this is the nature and purpose of theology. For many today the notion of theology is tied not to the concept of revelation, an act of God, but to religion, a purely human act. We should thus also take a close look at the sense of the term theology when it is linked to the concept of religion.

1.1.2. Theology and Religion

For some, the essence of the biblical faith is religion, not revelation, thus the task of theology is the explication of religious beliefs. The historian Emanuel Hirsch has argued that this view of theology owes its origin and development to the influential eighteenth-century theologian Sigmund Jacob Baumgarten. For Baumgarten revelation was separated from Scripture, and Scripture was turned into a human expression (religio) of divine revelation. As Baumgarten used the term, revelation was the “manifestation of things previously unknown.”8 On the other hand, for Baumgarten, the term inspiration was understood as “the means by which direct revelation was communicated and recorded in books.”9 Thus for Baumgarten, divine revelation was not identified with Scripture, but rather, Scripture was identified as the recording of that which had been communicated directly to the mind of the biblical writers. This is, admittedly, a subtle distinction, but it is one that had far-reaching consequences. Hirsch states that “German Protestant theology reached a decisive stage with Baumgarten. It went from being a faith based on the Bible to being one based on revelation—a revelation for which the Bible was in reality nothing more than a record once given.” For Baumgarten and those that followed him the Bible was not divine revelation, but a response to a divine revelation. As such the Bible was a religious artifact, not itself a divine revelation.10 Within such a view of the Bible and revelation, theology becomes the statement of the religious opinions and beliefs of those with whom and among whom God has acted.

It is important to note that this understanding of theology differs from that of the previous understanding in one basic respect: as an explication of religion rather than revelation, theology does not stand at the end of a special process initiated by God, but rather of one initiated by man. Religion, as it is thus understood, is a human act. God may have acted in history and in the affairs of his people revealing himself in many ways. All this is still possible within this understanding of theology. But the important distinction is that theology’s task is seen as the explication of the religious consequences of God’s acts or of God’s work, not a reckoning of God’s revelation itself.

The net effect of such a distinction is to remove the normative status from the concept of theology. Theology is understood as a restatement of man’s beliefs about God and humanity. It does not venture to recount God’s will as such. How, then, does this view of theology affect one’s understanding of OT theology? In this sense, OT theology has the task of merely recounting what the biblical writers believed or held to be true about God. Theology, then, should not say, “Thus says the Lord”; it can only say, “This they believed.”

It is not hard to see that such a view of theology, like the former, gives rise to several interesting questions. By removing from it any claim to be normative, this understanding of theology has cut itself off from the community of faith, the church. The church, which must have a norm or a standard by which to measure its own life and action, cannot look to theology, at least not biblical theology. The trail pursued by theology leads back to a human initiative in establishing a religion rather than to God’s act of revelation. The theologian ultimately finds one like himself at the other end of his quest. The Scriptures were a product of divine revelation, not a source of that revelation. The church, likewise, finds only itself as a community on either end of the line running from human beliefs about God (religion), to human expression of those beliefs (theology). There is no basis for a claim to authority. The church cannot hear the Word of God if it only hears human words when it reads the Old Testament. If the OT theologian hears only human words, how does the church know when they are hearing the Word of God?

1.1.3. Summary

There are, then, at least two distinct ways to understand the task and nature of theology. The point of departure between the two ideas is the question of whether the Bible is a record of God’s revelation or of human religion. The consequence of the distinction in meaning is the question of authority. Does theology have a right to make claims about the normativity of its statements? Does theology stand at one end of a special process begun by God, or is it a purely human enterprise? Can the theologian ever hope to say to the church, “Thus saith the Lord”?

1.1.4. Should Theology Claim to Be Normative?

In the last analysis, the question that must be addressed by anyone wishing to understand OT theology is whether such a theology is to be understood as normative for the Christian today. Is one’s theology to be taken as binding because it is a restatement of what God himself has revealed? Or is theology merely the description of human beliefs about God? In short: has God spoken? Is the Bible a record of what God has said? Can we claim, or dare, to speak God’s word as it has come to us in the OT?

Although much of this book is an attempt at addressing these questions, certain points are assumed from the start and should be set forth clearly here at the beginning of our discussion. These are not to be understood as presuppositions that are beyond defense or argument. They are rather part of a theological prolegomena that lies outside the scope of this book. They are given here, not as a basis for proceeding with the description of OT theology, but as a basis for understanding the author’s own theological commitment. They will affect the nature of the author’s own proposal for doing OT theology, however, as will become evident throughout the book.

In the first place, I take it that the Bible is the Word of God and that in the Bible God has spoken. The Bible is not merely a record of what God said in the past; it is, in fact, a record of what God is saying today. By means of the words of the Scriptures, God has spoken and speaks to us today.

If God has spoken in the Bible, then the task of theology is made considerably more clear. The task of theology is to state God’s Word to the church in a clear and precise manner. What else can be expected of theology than an understandable restatement of the Word of God?

Such is the understanding of the term theology in the mind of the author of this book. Theology is the restatement and explication of God’s revelation, the Bible. It intends to state what should be heard as normative for the faith and practice of the Christian believer.

In light of what has been said here about the task of theology, we should remember that theology, like all other fields of study, is a human endeavor. As such it is subject to all the limitations of human fallibility. No statement of the Bible’s theological message can claim to speak with the same authority as the Bible itself. Only the Bible is infallible, not our theological systems.

1.2. DEFINITION OF OLD TESTAMENT THEOLOGY

Having gained some understanding of the goal of theology, we can now look more closely at the nature of OT theology. No single definition of a field so diverse can hope to please everyone or claim to be comprehensive. We should also keep in mind that this definition is largely determined by the set of assumptions about Scripture and revelation discussed in the previous section. A definition will be helpful as long as it is understood not to be exclusive but to be only an aid to further understanding and clarification. In other words we should not think of a definition as a way of ruling out different approaches. It should rather be seen merely as a way of setting our objectives more clearly in sight. The following definition is offered with that end in view: Old Testament theology is the study and presentation of what is revealed in the Old Testament.

Although this is a simple definition, it raises at least four important issues about which there is much debate.

1.2.1. The Study of the Old Testament

The first feature of OT theology reflected in the definition is the idea that an important dimension is the study of the OT. Whether study rightly deserves a place in the desc...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- PREFACE

- ABBREVIATIONS

- PART I INTRODUCTION

- PART II THE METHODOLOGY OF OLD TESTAMENT THEOLOGY

- PART III A CANONICAL THEOLOGY OF THE OLD TESTAMENT

- APPENDIX A: THE MOSAIC LAW AND THE THEOLOGY OF THE PENTATEUCH

- APPENDIX B: COMPOSITIONAL STRATEGIES INTHE PENTATEUCH

- APPENDIX C: THE NARRATIVE WORLD OF GENESIS

- APPENDIX D: 1 CHRONICLES 21:1—A STUDYIN INTER-BIBLICAL INTERPRETATION

- Other Books By John H. Sailhamer

- Copyright

- About the Publisher

- Share Your Thoughts