![]()

1

Anthropology and Missions

A young missionary had just arrived in the interior of Kalimantan, Indonesia, fresh from language training. She was glad to be working among the Dayak people. She had heard about the explosive growth of the church in this area. She was excited about being part of this dynamic church planting ministry.

However, as time passed and she observed how the church was growing, she began to be bothered. The Dayak were not coming to Christ as individuals, but as households. It appeared to her to be a communal decision rather than an individual decision. This disturbed her because she had always been taught that conversion was an individual choice. One had to respond personally to the gospel.

This young missionary began to question if the Dayak Christians were truly born again. She began to wonder if the missionaries who had worked with the Dayak for years were more interested in “church growth” than true conversions.

What is the role of cultural anthropology in Christian missions? Is it the answer to all that ails missions or a secular tool some missionaries use instead of relying on the Holy Spirit? These are two extremes. The role of cultural anthropology in missions is neither of these.

Cultural anthropology is not a cure-all for missions. It is just one tool of a well-prepared missionary. Neither does cultural anthropology replace the Holy Spirit. No real missionary work takes place apart from the Holy Spirit. However, many Christians misunderstand the role and place cultural anthropology can have in effective ministry.

Imagine a missionary couple working among a group of tribes located along a jungle river. To reach these scattered tribes they need a boat to travel the river. They have found some scrap iron and other materials left behind by an oil-exploration crew. Using these materials, they begin to build a boat, but they know little about physics and boat building. In the end the boat turns out to be heavier than the water it displaces.

Anyone who has studied elementary physics knows that an object that is heavier than the water it displaces will sink. “Oh, but in this case the Holy Spirit will overrule, and the boat will float. After all, it was built for God’s work,” some might say. No. The missionaries were foolish. They should have built the boat in keeping with the laws of nature.

This same principle applies to presenting the gospel to people of another culture. Since we do not expect God to overrule when we go against natural laws, why do we expect Him to overrule when we go against cultural or behavioral laws?

Just as there is underlying order in nature, so there is underlying order in human behavior. The behavioral sciences are concerned with discovering the underlying order in human behavior just as the natural sciences are concerned with discovering the order in nature.1 True science, natural and behavioral, is concerned with discovering the order in God’s creation.

The missionary who uses cultural anthropology as a tool in developing a missionary strategy is not trying to work apart from the Holy Spirit but in harmony with Him. Peter Wagner of the School of World Mission at Fuller Theological Seminary points out the need for strategy:

The Holy Spirit is the controlling factor in missionary work, and the glory for the results go to Him. But, for reasons we have not been informed of, God has chosen to use human beings to accomplish His evangelistic purposes in the world. These human beings, missionaries in this particular case, may well become obstacles to the work of the Holy Spirit, just as they may well be effective instruments in God’s hands. . . .

Missionary strategy is never intended to be a substitute for the Holy Spirit. Proper strategy is Spirit-inspired and Spirit-governed. Rather than competing with the Holy Spirit, strategy is to be used by the Holy Spirit (1971:15).

James F. Engel and H. Wilbert Norton of the Wheaton Graduate School of Theology in discussing the biblical pattern of evangelization say:

One theme that consistently runs throughout the New Testament is that the Holy Spirit works by renewing our mind (see Eph. 4:23; 1 Pet. 1:13; Rom. 12:2). We are expected to analyze, to collect information, to measure effectiveness—in short, to be effective managers of the resources God has given us. Unless we undertake this discipline . . . we effectively prevent the Holy Spirit from leading us! The ever present danger is that “a man may ruin his chances by his own foolishness and then blame it on the Lord” (Prov. 19:3, Living Bible) (1975:40).

As we have said, cultural anthropology is not a cure-all for missions nor a human effort working apart from the Holy Spirit. What, then, is the role of cultural anthropology in missions? Cultural anthropology may contribute in at least four ways to an effective missionary strategy:

- It gives the missionary understanding of another culture.

- It aids the missionary in entering another culture.

- It facilitates the communicating of the gospel in another culture.

- It aids in the process of planting the church in another culture.

Understanding Another Culture

A distinction should be drawn between mission and missions, according to missions scholar George Peters (1972). Mission is the total biblical mandate of the church of Jesus Christ. Missions is local assemblies or groups of assemblies sending authorized persons to other cultures to evangelize and plant indigenous assemblies. Missions is one aspect of mission. Basically, missions is the church in one culture sending workers to another culture to evangelize and disciple.

The preceding definition emphasizes moving from one culture to another, not from one nation to another.2 National boundaries are artificial lines drawn on maps by politicians; cultures are realities in geographical localities. Someone from New York who ministers to the Pima Indians of the American Southwest is just as much involved in a crosscultural ministry as the New Yorker who ministers to the Mapuche Indians of Chile.

One who intends to minister to another culture needs to become familiar with the other culture. Although basic behavioral laws or universals underlie all human behavior, this behavior takes various forms in different cultures. In order to function in another culture, a person must understand that culture. Cultural anthropology provides the conceptual tools necessary to begin that process.3

Entering Another Culture

To minister in another culture, one must enter the culture. When an individual leaves his or her own culture with its familiar customs, traditions, social patterns, and way of life, the individual quickly begins to feel like a fish out of water and must either begin to adjust to the new culture or be tossed and buffeted by it until he or she finally succumbs to exhaustion and suffocation.

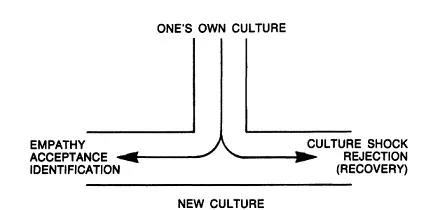

A person will respond to the new culture in one of two ways: with empathy, acceptance, and identification, which will result in adjustment and success, or with culture shock and ultimate failure. Often culture shock is

precipitated by the anxiety that results from losing all our familiar signs and symbols of social intercourse. These signs or cues include the thousand and one ways in which we orient ourselves to the situations of daily life: when we shake hands and what to say when we meet people, when and how to give tips, how to give orders to servants, how to make purchases, when to accept and refuse invitations, when to take statements seriously and when not. Now these cues which may be words, gestures, facial expressions, customs, or norms are acquired by all of us in the course of growing up and are as much a part of our culture as the language we speak or the beliefs we accept.

Now when an individual enters a strange culture, all or most of these familiar cues are removed. . . . No matter how broadminded or full of good will you may be, series of props have been knocked from under you, followed by a feeling of frustration and anxiety (Oberg 1960:177).

Culture shock comes in three stages. First is the fascination, or tourist stage, which comes when the person first enters the new culture. There are new and fascinating sights and sounds. There are exciting things to see and experience. There are usually friendly, English-speaking people to help and see to one’s comforts. The tourist, or short-term visitor, usually never goes beyond this stage before leaving the host culture.

Figure 1-1. TWO REACTIONS TO A NEW CULTURE. When people leave their own culture and move into a new culture, they can move in one of two directions—either toward empathy, acceptance, and identification or toward culture shock and rejection (and possible recovery).

The second stage is the rejection stage. The fun and fascination of the new culture begin to fade, and the newcomer meets head-on the difficulties involved in living in the new culture. But now the “rules” of living are different, and the newcomer is not “in” on most of them. The way of doing things in the person’s own culture may have been neat and logical, but the ways of doing things in the new culture may seem capricious, without design or purpose. The newcomer becomes frustrated in attempting to function in the new culture by applying the “rules” of his or her own culture. When these “rules” do not accomplish the desired results, the person blames the new culture; and he or she begins to reject the new culture.

This rejection may take several forms, such as stereotyping members of the new culture, making derogatory and joking remarks about the people, dissociating oneself as much as possible from members of the new culture, and associating as much as possible with members of one’s own culture. Most people make at least a partial recovery from culture shock. Those not able to accommodate themselves to the new culture eventually withdraw from it completely.

The third stage, recovery, begins as the person starts to learn the language or dialect of the new culture and some of the “rules” of the new culture. As the person begins to adjust to the new culture, the frustration subsides. The degree of recovery from culture shock varies from person to person. Some people spend a lifetime in another culture at a level just above the toleration point, while others fit right in after only a short time.

Cultural anthropology can give people a perspective that will enable them to enter another culture with the least amount of culture shock and the quickest recovery, enabling them to begin to move toward empathy, acceptance, and identification. This perspective is built on the concepts of ethnocentrism and cultural relativism.

Ethnocentrism is the “practice of interpreting and evaluating behavior and objects by reference to the standards of one’s own culture rather than by those of the culture to which they belong” (Himes 1968:485). Cultural relativism is the “practice of interpreting and evaluating behavior and objects by reference to the normative and value standards of the culture to which the behavior or objects belong” (484).

These definitions show that ethnocentrism is a way of viewing the world in terms of one’s own culture. An action is right or wrong as defined by one’s own culture. Other ways of doing things in different cultures make sense or do not make sense, depending on how they are viewed in one’s own culture. Cultural relativism is a way of viewing the world in terms of the relevant culture, that is, in terms of the culture in which one finds oneself. An action is right or wrong as defined by the relevant culture.4

People entering another culture should recognize their own ethnoc...