![]() PART ONE

PART ONE

Language in Comics![]()

Chapter One

Arbitrary Minimal Units in Krazy Kat

Comics critics’ default justification for asserting that comics are a literary form is that, like prose fiction, they tell stories. Time and again, “themes, plots, and characterisations” (Lombard et al. 1999: 23) are emphasized in discussions of comics’ literary properties. Their parity with verbal literary forms is couched in terms of generic narrative attributes or, even more diffusely, as lying in such sweeping artistic values as being “creative, original, well-structured, and unified” (Meskin 2009: 220). George Herriman’s Krazy Kat ran in the newspapers of William Randolph Hearst from 1913 to 1944, its core plot repeated day after day: mouse throws brick at cat; dog arrests mouse. Few critics would argue that complex “literary” themes may be found in this repetitive riffing, and in the case of Herriman, it has been said that critical attention is usually devoted to his “peerless drawing skills, while his writing tends to be scanted” (Heer 2008: 7). Herriman’s writing is, in fact, often referred to, though the general critical tendency to downplay linguistic content risks a scandalous neglect of the precise mechanics of his dazzlingly virtuoso writing. In his brief analysis of Herriman’s linguistic ingenuity, Jeet Heer compares his writing style to the “exhibitionist speechifying” of the carnival barkers, newspapers hawkers, sports announcers and traveling salesmen of his day, men who profited by a “glib and copious tongue” (2008: 8). Certainly, Herriman was a master of grandiloquent garrulousness, as evidenced by the sales pitch: “It will nectarize every nick in your neck and starch a shirt – lend lilt and loquacity to every line of your language – raise a mess of muscle that’ll toss a ton with tidiness – burnish your buttons, buzzers and badges – and put a kamel’s kick in your katnip – and now the sultan will pass among you with this elixir of the elite – potation of potentates – nobles’ nippage” (Herriman 2006: 13).

Herriman’s literariness does not lie in his ability to construct a story, nor can any comics’ narrative content be used as evidence for their literary prowess. Indeed, “A ballet can be a narrative. A hospital chart can be a narrative. A stock-market report can be a narrative” (Lewis 2010: 77). But none of these things are literature, and though comics’ narratives can be constructed in highly artistic ways, a text’s literariness lies in the formal features of its language, not the fact it happens to communicate a story. Due to the supposed hierarchy between words and images, critics place a great deal of emphasis on communicative serviceability. French critic Thierry Groensteen objects to this “all too functionalist conception of the story in images” (2009b: 126), which privileges the utilitarian information value of pictures. Protesting against those earnest explanations that pictures are “as capable as words of communicating ideas,” Groensteen advocates an approach that “restore[s] to the image its true semantic richness (and the arising emotional dimension), that the reduction to a linguistic statement corresponding to its immediate narrative ‘message’ tends to mechanically overshadow” (2009b: 121). This “mechanical reduction” aptly characterizes what Anglophone comics critics have often tended to make of semiotics in general, and the relationship of this problem to semantically rich images will be addressed in due course. What Herriman’s work in particular highlights is the corresponding problem of treating textual content this way, emphasizing story information rather than the language-specific formal features of literary writing.

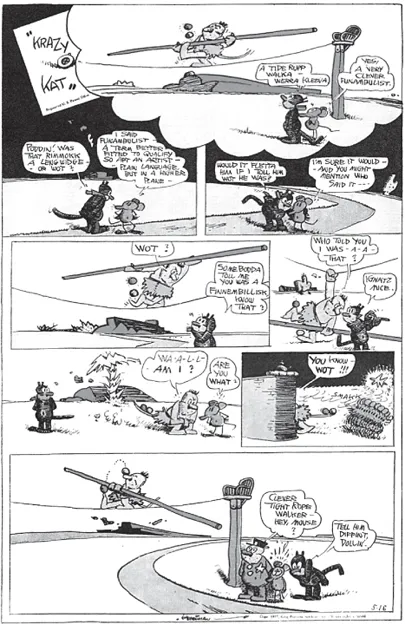

Critics’ ongoing preoccupation with the idea that pictures must definitively tell the bulk of the story (Horrocks 2001: 5, Meskin 2007: 369) demonstrates the way words as well as pictures are treated as vehicles of a message whose aesthetic qualities, the “emotional force and presence that cannot be entirely reduced to meaning” (Petersen 2009: 165), are neglected. According to the customary formulation of literature as storytelling (which rather perversely aligns narratology with literature, though no comics critic would credit the assumption that prose literature is the default narrative form), Herriman’s repetitive and ridiculous micro-plot hardly warrants literary analysis. However, a more exacting characterization of literary writing is found in Jonathan Culler’s assertion that though “literature is clearly a form of communication, it is cut off from the immediate pragmatic purposes which simplify other sign situations” (1981: 35). This viewpoint echoes Groensteen’s assertion that the artistic contribution of comics’ visual element “cannot be evaluated in terms of information” (2009b: 126). Once we abandon the general critical reluctance to focus on verbal content, it soon becomes clear that Herriman’s text is intensely poetic, aesthetically rich, and inventively comical; and it is this, rather than the pragmatic communication value of his writing, that presents the most convincing case for comics’ potential literariness. Herriman possessed “a poet’s ability to have fun with words” (Heer 2008: 9). His strips are less concerned with the utilitarian conveyance of a message that critics’ preoccupation with story and themes over-emphasizes, and more with a playful treatment of the formal surface features of language. Words proliferate, not in service of conveying more meaning, but for their own aesthetic sake. His manipulation of linguistic possibilities took many forms and an exemplary grain of just about all of them can be found in the strip above (Fig. 1.1).

1.1 George Herriman, Krazy & Ignatz: 1937–1938, ed. by Bill Blackbeard (Seattle: Fantagraphics, 2006), p. 31 (original publication date 16 May 1937).

Krazy Kat, an endearing dolt of indeterminate gender, watches the performance of a “tide rupp wokka,” termed by his more ornately eloquent acquaintance, Ignatz Mouse, a “funambulist.” The high-flown formalism is typical, as is Krazy’s mildly bemused, heavily phoneticized response: “Poddin’, was that rimmok a lengwidge – or wot?” In Ignatz’s response, “I said funambulist – a term better fitted to qualify so apt an artist – plain language, but in a higher plane,” Herriman pulls off several of his favorite tricks. The high register his characters so often favor is evidenced by the ceremonially decorous vocabulary, with the slightly anomalous use of “qualify” to signify naming or describing sounding convincingly grandiose. The self-consciously literary feeling generated by this lofty tone is complemented by the alliteration of “so apt an artist,” a habitual device that tends to lend a gently silly singsong air even as it emphasizes the lyrical elegance of these elevated constructions. Alliteration plays off words’ sound qualities, and Herriman has a keen ear for language’s potential musicality. Homophones, homonyms, and synonyms are particularly beloved, exploiting the excess of signification that “is always a threat to order” (Lecercle 1985: 95) in language. “[P]lain language” is here neatly subverted by the “higher plane” which aurally echoes its counterpart and baffles the cat with terminology that is anything but plain. Language’s graphic and phonic forms are made to duel with one another here, and are further exploited by Herriman through the vague and mangled phonetic formulations of Krazy Kat—who, in this strip, parrots Ignatz’s term as “finnembillisk.” Krazy is often befuddled by language. This confusion manifests itself in the transposing of approximate syllables to create a kind of colloquial pidgin dialect (such as “poddin” for “pardon,” “diffint” for “different”) and in the explicit perplexity that is expressed here. The cat is frequently stumped by language’s slipperiness, wrong-footed by illogicalities such as homophones, and language’s continual refusal to follow its own rules.

These features form the core threads of Herriman’s giddy volubility: the slipperiness of language and its proliferations of meaning; the graphic-phonic forms and ways their refusal to absolutely concur can be used to great effect; and the different registers language can be organized into, on which Herriman draws. The aim, in appraising these in turn, is to demonstrate how vital these specific features of language are to its literary effects. These effects show how wrong critics are to sideline language in comics, and suppress the peculiarities of different signifying systems in service of proving their equality. This chapter will also take a very brief look at how Herriman’s delirious poetry reflects a twin “visual loopiness” (Wolk 2007: 355) as, obviously, comics can never be comprehensively grasped by looking at only linguistic content. But the tacit agenda in deliberately sidelining visual (and thematic) content in favor of linguistic, is to illustrate how comics might truly be approached as literature, and to present a more convincing argument than has previously been achieved for their literary potential.

The first point of inquiry concerns language’s minimal units. Herriman plays with the articulations that divide the temporal stream of sound into discrete linguistic units. Humorous misformulations are generally uttered by Krazy who, for example, consoles dog and mouse, both suffering acute indigestion, that “annie ho, it’s a cute illment” (Herriman 2006: 43). The joke here derives from drawing the divisions that separate words in different places. Herriman makes a game out of this with the tale of Sir William Bee, taking the innocent word “bumble” and drawing out the hidden morpheme that is integrated into a multi-syllable, minimally significant unit. Those first three letters act as a phoneme here, though when taken alone they have their own separate significance: Sir William, for a social misdemeanor, is dubbed “bum” by the Queen, and henceforth is “To society ‘Sir William Bee’, To his peers, ‘Bill Bee’ – And to the world today ‘Bum-Bill Bee’” (Herriman 2008: 47). This joke works by finding a smaller significant unit within the minimal unit “bumble” and artificially segregating its two phonemes by transmuting the non-significant “-ble” ending into “Bill,” cheekily freeing up the other, which happens to have its own meaning.

Beyond this playful approach to the articulation of units, Herriman coins words that depend on recognized morphemes for ungrammatical but clearly decipherable significance. Heer has pointed out that “it’s easy enough to classify [Herriman] as a nonsense poet,” but that “he usually doesn’t make words up however much he might twist them around” (2008: 7–8). Indeed, Nonsense-like as Herriman often sounds, his linguistic constructions are free from the “snarks” and “dongs” of true Nonsense poets like Lewis Carroll and Edward Lear. He is not, however, hemmed in by “correct” linguistic constructions, operating instead at the edges of what is permitted by the linguistic system. Exemplary is Officer Pupp’s pronouncement on the pot plant he stumbles across: “A potted ‘cactus’ – what a waste of pottage – and when such pretty posy plants like peonies, petunias and pansies are pleading for potment” (Herriman 2007: 18). This takes the morpheme “pot” and creates from it two verbal nouns, both of which refer to “the state of being potted.” No such words exist (or, at least, they do not attach to the significance they are given here according to any dictionary), but in this utterance, they make perfect sense.

Such examples illustrate Jean-Jacques Lecercle’s assertion that, paradoxically, “what lies outside language is still within language” (1985: 88). Lecercle claims that the unruly, unsystematic “outside” of language—which he terms délire—is in fact integral to constituting the orderly, systematic “inside.” He avers that every rule of grammar draws a border between what can and cannot be said, but notes that “there are linguistic values, which distinguish correct or “normal” language from délire, and yet the rejected elements play a part in the constitution of linguistic values” (Lecercle 1985: 89). That is to say, that which belongs to the system is defined in relation to what lies outside it. The very incorrectness of certain linguistic utterances (“potment”) plays a part in drawing the frontier between these misconstructions and correct language (“potted”). Herriman shows that the border between sayable and unsayable can be crossed: the word “potment” does not exist according to the dictionary, and “pottage” here takes on a very different meaning, but though both are recognizably linguistically incorrect, they can be said and can be invested with significance. The relationship between the elements inside and outside of language, which here each draw the same morpheme into correct and incorrect constructions, enables the non- or extralinguistic phrase to signify nonetheless. However, its significance incorporates misarticulation. The sense of these coinages depends on the differentiation of correct and incorrect, and in playing with this frontier in a way that foregrounds its existence, Herriman here exemplifies “an utterance that, at the very moment it plays havoc with language, acknowledges the domination of the rules it transgresses” (Lecercle 1985: 55). In recognizing that a rule has been broken, we must also acknowledge the existence of the rule being flouted.

Herriman does not exemplify Lecercle’s concept of radically disruptive délire, but rather compares with the benign Nonsense of Lewis Carroll, in which “frontiers are temporarily forgotten” (Lecercle 1985: 78). Lecercle identifies an opposition in language between “the dictionary” (language as an abstract, systematic tool of communication) and “the scream” (language as a material, individual expression of the passions, instincts, and drives of the body). True délire is sense-devouring, “raucous, violent, full of consonants and unpronounceable sounds, of screams and hoarse whispers” (Lecercle 1985: 41). Herriman’s language-play, like Carroll’s, “belongs to the surface, it abides by all the rules and conventions, it is highly grammatical and engages in games (e.g. the portmanteau words) which do not threaten, but on the contrary reinforce it” (Lecercle 1985: 41). Herriman’s games, though seemingly anarchic and wilful, in fact sustain sense and order. Words that are not quite words are given meaning, and their linguistic value—their very literary effectiveness—is in part gleaned from the sense that they violate the rules of the linguistic system, which are thus tacitly reinforced. In Herriman’s coinages, morphemes that are constitutive parts of the linguistic system lend meaning to linguistic constructions not instituted into that system, creating a pseudo-Nonsense effect that is at once playful, expressive, and highly literary.

Examples abound of this creative coinage of words from the langue’s permitted morphemes. The oft repeated “jailment” (Herriman 2008: 35) makes a noun from the verb “to jail,” a word describing not an action but a quantifiable thing that the cop “administer[s]” (Herriman 2006: 24), and whose syntactic construction adds to the illustrious tone. Similarly, “how I unadmire him” (Herriman 2008: 48) ventures a logical, but unapproved combination of units, while “a lot of foolishment” (Herriman 2007: 100) makes noun from adjective. These violations of the system bear witness to the existence of the very rules they break: “The flouting of linguistic and literary conventions by which literary works bring about a renewal of perception testifies to the importance of a system of conventions as the basis of literary signification” (Lecercle 1985: 37). The institution of a linguistic rule presupposes that the rule can be broken, but this flouting in turn testifies to the existence of that rule, which sanctifies or denies the utterance that conforms with or flouts it. As discussed in the introduction, visual signification is far freer, not only to use signs out of context but also to form signs anew (as we shall see in Chapter Seven). Herriman adroitly demonstrates here that it is possible also to coin new sign forms in language, but the rules that designate the coinages as “outside” the linguistic system are precisely what lend his writing its off-the-wall flavor. Indeed, everywhere in Herriman’s writing the jubilant ingenuity of his gymnastic inventiveness is derived from the sense he is in breach of established rules. It is the very palpable authority of those temporarily discarded rules that makes his writing sound so wildly colorful.

The sense of gleefully eccentric creativity within Herriman’s writing is furthered by the false aggrandizement of words alluded to above. Herriman plays with language’s minimal units by lengthening them, turning them into more elaborate terms, but ones not actually recognized as belonging to the linguistic system. The “-age” ending is appended to words at will, as when Officer Pupp declares that Ignatz’s “sinful tossage of bricks” could be dealt with by “more tappage of this smacker” (his truncheon), embellishing the two units “toss” and “tap” with the orotund-sounding ending. This lackadaisical approach to grammar creates ornate words from simple ones, but elsewhere, as operated by Krazy Kat, conjures up guileless, yet expressive formulations. Noting that Officer Pupp is “bitzy injoyin’ himself,” the cat decides “I’ll go fine Ignatz Mice an’ made myself injoyfil, too” (Herriman 2006: 12). With “tossage” and “tappage,” a recognizable suffix is applied in ways the langue does not recognize. The remit of the grammatical rule is extended to augment words to which it cannot correctly be applied. Krazy, on the other hand, obliterates these rules. Hanging on to the central morpheme “joy,” the cat layers up indiscriminate grammatical constructions, mashing together “enjoy” and “joyful” to create “injoyfil,” which alludes to the approximately equivalent sense of “fill” and “full” and misspells according to the cat’s peculiar phonetics as usual.

Minimal units are demonstrably integral to the operations of the linguistic system. Critics such as Groensteen question those who insist on the necessity of identifying minimal units for any signifying system (2009a: 2). This is a valid challenge insofar as there exist systems, such as visual images, which refute this prescription, as they demonstrably do not decompose into meaningful minimal units. However, it would be an error to extend this refutation into a denial of the relevance of minimal units to the operations of a system that is so constituted: language’s constitution in discrete, repeatable morphemes explains how the above examples generate the effects they do. So too is visual signification’s analogical nature relevant to its dynamics. Attempts have been made by some comics critics, such as Guy Gauthier, to artificially select “lines or groups of lines, spots or groups of spots, and to locate for each signifier thus determined, a precise signified” (Groensteen 2006: 3). Such efforts1 fail in the face of Eco’s semicircle/dot example, which proves that, though forms can be isolated within the visual continuum, “as soon as they are detected, they seem to dissolve again” (Eco 1976: 215), relying as they do on the surrounding context to imbue them with a “precise signified.” Verbal signifiers, on the other hand, are separable units whose association with a signified preexists their evocation in a particular context. However, the effect of deploying these signs in different contexts challenges the naive empiricism suggested by critics’ aforementioned tendency to characterize signs as vehicles for ideas.

In Herriman’s language game, the simplistic idea that any “precise” or fixed meaning can be found even for language’s minimal units is challenged. Possible meanings proliferate “behind” (for want of a better word) the sign-forms that stand in for them, as in Krazy’s excited comment about his/her new-planted corn: “Now, I will have korn bread, korn mill mutch, korn poems, korn plestas, korn kopias” (Herriman 2008: 64). Here, signifier starts to come unstuck from signified. The “corn” of “cornucopia” and “corn plaster” is rather different from that o...