![]()

Chapter 1

MASQUERADE DERIVATION, COSTUMES, AND BEHAVIOR

I became interested in masquerade performances while getting my degree in art in London. A Yoruba artist, Taiwo Emmanuel Jegede of the Keskidee Arts Center in England, taught us that the artist’s duty is to feed society’s soul. I was intrigued by a masquerade’s quality of “whole theater,” combining the other arts.1 I eventually researched the masquerade culture of the Igede people of Benue State, Nigeria. Although once used to ready warriors for war or to commemorate battle victories, Igede masquerades such as Onyantu, Aitah, Ogrinye, and Abakpa now appear primarily during funerals or during the New Yam Festival, which demarcates each agricultural year. I found that a masquerade’s performance is one of many voices within an event where an enhanced aesthetic is initiated by the conjunction of different art forms (Nicholls 1997, 64).2

During my research among the Igede, I found that ancestors were viewed as being of the dawn or the beginning and as conservative and concerned with the continuity of tradition. Yet because the dawn recurs each day, they are also connected with rebirth and renewal, creation and creativity. This viewpoint suggests not only that old things can be regenerated as new things but that old ancestral things such as masquerades can possess an immediacy that makes them appear as vital and new. In modern day soca and calypso parlance, the word wind (pronounced “wine”) refers to the pelvic rotations characteristic of many African-derived dances. Similarly, work (pronounced “wuk”) is currently used to refer to dance. It might be assumed that these are relatively modern terms, probably not more than thirty or forty years old. Yet more than two centuries ago, Moreton (1790, 14–15) documented a dance song in Jamaica that includes these terms:

Hipsaw! my deaa! You no shake like a-me!

You no wind like-me! Go, yondaa!

Hipsaw! my deaa! You no jig like a-me!

You no work like a-me! You no sweet him like a-me!

This lyric exposes the vintage of the customs that are researched here as well as the context that implies that they can appear fashionable and new despite their age. Authentic masquerades possess something of this quality, seeming fresh and novel on each encounter. Although Ronald Hutton (1997, 94) launched his academic career by calling the antiquity of the British animal disguises of the early nineteenth century into question, he concedes that the “nature of the entertainment,” if not the physical artifact, has “remained consistent” over the years and that the impression of antiquity cannot be denied. Furthermore, he points out,

E. C. Cawte shrewdly commented that the experience of being inside a hooden horse has an odd character of its own, involving a sense of slackening responsibility for what occurs as the role of playing the creature takes over. The present author, who has had that experience, must agree, and testify to the nervousness in the laughter of most spectators at the approach of something that is, and yet is not, a human being. . . . These customs do have a way of communicating something genuinely archaic, whatever their actual age. (94)

On arriving in the Virgin Islands (VI), I was pleased to discover that Caribbean masquerading did not simply consist of John Canoe in Jamaica but was part of the heritage of the Eastern Caribbean. Professor Ruth Beagles (pers. comm., July 10, 1995) told me that when she was growing up in Christiansted, St. Croix, she would hear the “jing-jing-jing” of the steel triangle in the Christmas celebration and run to the window of her two-story house to throw coins down to a small group of musicians and a masquerade, maybe Lucifer with horns, or Donkey Mas’ dancing to the tune “Donkey want water, hold him down.” I decided to explore Eastern Caribbean masquerading in more depth and thereby to discover its historical influence on today’s carnivals.3

Each Caribbean Island has a carnival, but they are held at different times of the year. Dominica, Guadeloupe, Martinique, and Trinidad keep their carnivals true to Catholic tradition as pre-Lenten bacchanals ending on Ash Wednesday, like the New Orleans Mardi Gras. Anguilla, Antigua, Grenada, and Tortola hold their carnivals at the beginning of August to commemorate emancipation in the former British West Indies (BWI); St. Kitts–Nevis, Montserrat, St. Croix, and the Bahamas hold their festivals at Christmas, perpetuating ancient turn-of-the-year traditions. (Nevis also features Culturama in August.) Still others hold their carnivals at distinctive times. In Barbados, the carnival is held in June or July and is a continuation of the old Crop Over Festival, which celebrates the sugarcane harvest. St. Martin holds its carnival on April 30, the birthday of Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands. St. Thomas also has its carnival at the end of April, simply to extend the tourist season.

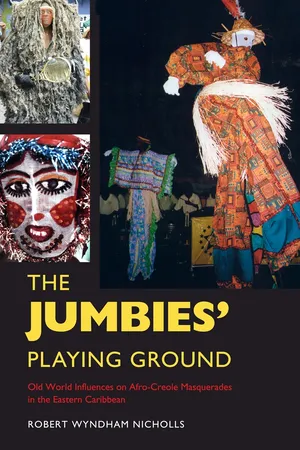

The masquerades of the different islands are similar, though their festivals’ Creole names may vary. Dominica has a Mocko Jumbie stilt masquerade known as Bwa Bwa; a donkey or burrokeet; a cow-horned shaggy masquerade known as Sensay Bull; and a raffia bear, which is the Sensay proper. (Plate 46) These masquerades are particularly prominent during the pre-Lenten carnival, Mas Domnik. Modern carnivals evolved from the earlier street masquerading that occurred primarily during the Christmas period and the New Year. S. B. Haynes (1872, 202) reports that on Three Kings’ Day 1872, “we had the unusual amusement of seeing the whole population of St. Thomas en masque. . . . The people were so delighted at exhibiting themselves in party-colored garments and false faces. . . . And we can never forget the striking effects produced by groups of these brilliantly tinted costumes beneath the glowing tropic sky, with the white West Indian houses for backgrounds.” A similar scene occurred in the first decade of the twentieth century: “What with the bright sunlight and the brighter colors displayed by the crowd of masqueraders, the Main Street from one end to the other seemed a kind of rainbow” (St. Thomas Bulletin, January 8, 1907). Literati described Caribbean slaves’ Christmas revels as a “Saturnalia” or “Bacchanalia.” Held in December, Saturnalia was an ancient Roman agricultural festival that was characterized by a symbolic reversal of power relations, whereby the meek appeared mighty and the mighty appeared meek. Tuckerman (1837, 24), for example, describes the 1836–37 Christmas and New Year’s activities in St. Croix as a “complete Saturnalia”: “The houses of the proprietors of slaves are thrown open; and long processions of slaves . . . with banners and music, enter at will the habitations to which they determine to go . . . are served with cakes and wine by their owners . . . and dance till they may be disposed to depart.”4 Throughout most of the nineteenth century, playing mas’ turned the world topsy-turvy at Christmas, and disguised performers roamed the streets. Mock aristocracy and their retinues performed Plait Pole (Maypole) in yards and pastures; ritualized battles broke out between Zulus and “Wile Injuns”; men dressed as women, and vice versa; tall Jumbies danced on stilts; Bluebell Girls tantalized bystanders with glimpses of frilly petticoats and pantalets; David and Goliath reenacted their epic battle on street corners; and the Shaggy Bear and Wild Bull chased children and danced to the music of the fife and drum.

For the Jola and others in Upper Guinea, transitioning to manhood involved becoming “a bull,” dancing in a horned mask and generally embodying masculine values: “strength, sexual potency, and . . . aggressive retaliation” (Mark 1992, 53). Such statements hold true for the Caribbean as well, although jocularity should be added because the Caribbean Bull was often comical. Although the literature might suggest that the involvement of women is less common elsewhere, in the Danish West Indies and in other parts of the Leeward Islands, women wore masks within women’s troupes such as Mother Hubbard and dressed down within Cane Cutters troupes, as the literature, oral reports, and photographs attest. (For women’s costumes as vehicles of enhancement rather than the disguise, see Franco 1998; Bettelheim 1998.)

Contemporary carnivals often give old masquerades a new lease on life and perpetuate the ancient custom as a living tradition. St. Thomas is a case in point. Carnivals were held in 1912 and 1914 but then lapsed until 1952, when Carnival was reestablished as an annual event. The roster of the 1952 and 1953 Carnivals shows that the parade drew on established Christmas masquerades. For example, Magnus the stilt-dancing Mocko Jumbie appeared in 1952 and 1953, as did the bear, Plait Pole, Indians, Zulus, clowns, and big heads. In the 1952 carnival, David and Goliath and a Down South troupe (blackface minstrels) appeared; the following year saw women’s Blue Belles, Old Fashioned Pantalets, and Mother Hubbard troupes as well as an entry dubbed Old Fashioned Masquerade. In most cases, island carnivals liberally showcased traditional masquerades or modified or borrowed from them. Following the Trinidadian model, Caribbean carnivals expanded to include majorettes, steel bands, large troupes, and elaborate floats (Liverpool 2001). Nevertheless, carnivals in the twenty-first-century Virgin Islands include Mocko Jumbies, Indians, Zulus, clowns, queens, and kings, while the Blue Belles and women’s contingents of yesteryear have been replaced by large troupes such as Hugga Bunch, Gypsies, or the Infernos that include women in skimpy costumes or spandex body stockings.

SCOPE OF THE STUDY

A masquerader is a street performer who entertains by dancing and other antics while disguised in a costume and usually a mask. In the Caribbean, masquerades historically were performed in the open air—on village greens, in urban compounds, in market squares, in yards, and on street corners. In colder climates, troupes might be invited into the parlor. In Britain, the terms guiser, mummer, hoodener, and wassailer are commonly used, along with more localized names such as Johnny Funny. More urbane characterizations included Merry Andrew and Jack Pudding and in earlier times a device, a droll, or an antick. According to the ethnic tongue, Africans have various names for disguised dancers, but in the English language, African guisers are generally referred to as masquerades or simply maskers. In the Upper Guinea, the Mandingo (Mandinka) masquerade, the Mumbo Jumbo, has been superseded by Kankuran, while I describe the horned Ejumba of the Jola (Diola), other West African masquerades, and Afro-Caribbean masquerades by their local names.

Barbados, the first British colony, had a Shaggy Bear (bush masquerade), Tilt-Man (Stilt-Man), Mother Sally (shemale), Donkey (tourney horse variety), and Donkey Man. Other early masquerades in the BWI included animal disguises such as the horse and the bull, including Cowhead Jonkonnu, and various clowns and Caribbean-style Merry Andrews, such as the Antiguan Highlanders. These characters unquestionably contain the residue of formative Old World seeds, but what Old World elements were adopted by Afro-Creole masquerades in the Eastern Caribbean, and how did transmission occur? The study looks for correspondence in appearance, roles, and behavior; where similarities arise, it fleshes out influences and potential attributive links. Social and spiritual roles of masquerading are discussed. Descriptions of the general appearance of a score of Caribbean masquerades are provided, including characteristic masks and costumes and musical components such as drum rhythms and song performances. Customary behavior and purposes are examined in areas of dancing, whipping, perambulations, demeanor, quêtes (traditional begging for food or alms to the accompaniment of folk song, specifically as part of a folk play), milieu, and social impact.

Paradigms of “dressing up” versus “dressing down” are explored. Dressing up uses a form of exaggerated realism and enhances rather than conceals the wearer (e.g., the Carnival Queen; see Cynthia Oliver 2009). In contrast, dressing down costumes lean to abstraction, are more amorphous, disguise the wearer, and may involve wearing sackcloth, raffia, and/or rags. For example, a bush masquerade such as the Shaggy Bear resembles nothing less than a mobile haystack. Pitchy Patchy and many of the Dominican Sensay masquerades are colorful cloth versions of the bush masquerades. (Plate 42) Moreover, some masquerades, such as the devil or bull, espouse an antisocial character. Because the Virgin Islands clown, Pitchy Patchy, and Montserrat masquerade are stylish and the Mocko Jumbie stilt masquerade is elegant, they might be considered dressed up. However, like the bush masquerades and animal representations, authentic renditions are totally disguised. In the past, gloves and stockings ensured that all human flesh was concealed. This fact, along with the name, Jumbie, connotes ancestral beliefs and interaction with the spirit world. Interviewed on television during the 2009 VI Carnival Parade, Carl Callwood, director of the Tropical Masqueraders Clown Troupe, explained that the masquerades “are based on our ancestors” and that their traditional function was “to scare away Jumbies.” Women’s genres include the dressed-down Cane Cutters in burlap costumes and the masked Mother Hubbard troupes with their tamarind whips.

A Jumbie (synonymous with Duppy) is a ghost or spirit. Referring to Guyana, Scoles (1885, 60) states, “Now Jumbie be it known is a great power out here, and . . . a sort of public pet, for so many things have been given or dedicated to him . . . such as trees, flowers, seeds, berries and birds.” This is generally true of the Lesser Antilles, where one finds not only Jumbie beads (Abrus precatorius) and Jumbie trees (e.g., Ceiba pentandra) but also Jumbie peppers (Rivina humilis), a shrub that has toxic berries used locally to treat diarrhea; Jumbie fingers, the seedpod of the pomshock tree (Inga laurina); Jumbie parasols, small white umbrella-shaped fungi; Jumbie crab, a small reddish land crab; Jumbie bird, the nightjar, with its eerie whirring warble; and Jumbie horse, the vernacular name for praying mantis.

The word Jumbie, like zombie, may derive from the Kimbundu word zumbi or nzambi, which generally means a spirit or deity, or from the Kikongo word njambi, which refers to a major deity (Gerhard Seibert, pers. comm., March 13, 2001; see also Kubik 1999, 24). However, it may have a duel provenance, because an alternative possibility from the Upper Guinea region exists in the Senegambian word bajumbi. Bajumbi is a pea-sized red and black seed of a vine (Abrus precatorius) that is believed to provide protection from bad spirits. Bajumbi seeds give their name to the Ejumba mask of the Jola in the Casamance region, a mask associated with male initiation ceremonies: “The ejumba mask covered with red seeds protects the new initiate” (Mark 1992, 103). (Plate 13) In the Eastern Caribbean, Abrus seeds (Jumbie beads, John Crow beads in Jamaica) are made into necklaces and bracelets to serve as protection against Jumbies and malevolent forces. Masquerades may also be decorated with Abrus for the same reason.

The term Jumbie reflects animistic ideas of spirits that inhabit natural phenomena such as trees and rocks and equates to African notions of the ancestors, particularly deceased kinfolk. Barbadians around 1817 “believed in the existence of spirits, which they call Jumbees, and sometimes spread victuals on graves . . . that their spirits might return and eat” (Watson 1817, 17). In St. Vincent, for some time after Nine Night (a funeral wake), “one is likely to see the first drops of any liquid being drunk thrown on the ground whether for the daddies (as the ancestors are called) or for a specific dead person. This is especially important to do at the crossroads or where people congregate in public” (Abrahams 1983, 180). Using edible offerings to remember the deceased was fairly common both throughout the Caribbean and in West Africa.5 Jumbies can be good or bad, but mostly they are mischievous. Tobagoans believe that “jumbies are restless spirits, the undead who pass their time playing tricks on the living” (Iaconetti 1997, 42). Theresa Lewis (1990, 43) explains the importance of “knowing whether it was a good jumbie or a bad jumbie. Bad jumbies could bring you the worst possible luck. . . . On the other hand, a good jumbie could also influence your surroundings and help to protect you.” Asta Williams (pers. comm., August 3, 2001) points out, “Spirits provide omens; they can alert you to a lot.” Regarding the Virgin Islands, Lito Valls (1981, 7) writes of a “Bapoo,” which he describes as a “Jumbee in a bottle”: “Bapoos are sometimes placed on fruit trees to keep children away.” In Jamaica, the term “dressing a garden” means “setting Obeah for the thieves” (Bell 1889/1970).

In relation to Jumbie protection, a confluence of Old World ideas occurred in the Caribbean. There is an old belief in Europe that wearing clothes inside out, wearing underwear outside of one’s regular clothes, or cross-dressing renders one invisible to evil spirits. In the VI, Frank Charles (pers. comm., July 1, 1996) recollects that “when going home late at night, someone might wear their clothes inside out to ward off ghosts.” The same is true for Antigua, where Samuel Smith states, “women use to turn their dresses over their head when walking at night and men use to turn their shirts on the wrong side” (Smith and Smith 1988, 67). This practice also occurs in Tobago and elsewhere (Iaconetti 1997, 42). If a ghost was felt to be in the vicinity, an Antiguan woman would throw her skirt over her head, stoop, and show the ghost her bloomered backside while uttering curse words (Lornetta Prince, pers. comm., August 2, 1995). The fact that the protective power is in the textile is evidenced by the fact that in the Virgin Islands, “You could prevent a jumbie from entering your home by turning your clothes inside out and hanging them on a line across the room. The jumbie will walk up and down outside, but it could never enter” (Schrader 1993, 89). Although she is now in her thirties, Crucian Tracy Warner (pers. comm., August 30, 1996) confirms that she will still “put on her pajamas inside out” to ward off ghosts.

Mocko Jumbie now refers exclusively to Caribbean stilt-dancing masquerades; in the Eastern Caribbean, however, the term previously referred to all masquerades. Furthermore, as a consequence of both the dialect of the informant and the partiality of the chronicler, there are many spelling variations of Mocko Jumbie (and Jonkonnu, for that matter). Moreover, the name both describes what it is and what it does. As an adjective, mock means “sham” or “artificial”; as a verb, the word means “to mimic” or “to ridicule.” A Mocko Jumbie, therefore, is an effigy—a supernatural scarecrow—that ridicules and scares away ghosts (Leona Watson, pers. comm., August 9, 1996). Mocou in colloquial Spanish means “spirit” or “ghost.” Some Virgin Island folktales tell of Jumbies dancing and being dispersed with a whip. In Antigua, the noise of stamping feet can dislodge spirits from a yard or from inside a house. A Mocko Jumbie’s presence is believed to have a negative effect on malevolent spirits and sorcerers. The Mande of Upper Guinea perceive the bush as a place of dibi and the world of sorcery as submerged in it. Masks are described as dibi-finw (things of dibi) that enter the world of obscurity to fight treachery and sorcery (McNaughton 1982, 58). Mama Konta, a Senegalese folklorist, discussed similar ideas at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival in Washington, D.C., in 1990. She said that when villagers dance in Senegal, they stamp their feet to keep away the evil spirits, which then take refuge in the trees, where only the stilt dancer can reach them to mock them and get rid of them. Jumbies in trees, stamping feet, and cracking whips are all familiar concepts in the Eastern Caribbean. Through Creolization processes, bloomers, petticoats, clothes turned inside out, and clothes of the opposite gender were seen as weapons to be used against Jumbies. Historically in the Virgin Islands, stilt masquerades often dressed in women’s clothes and would raise their outer skirts, show their underwear, and flutter or feather their petticoats to drive off evil spirits. According to Rudy Farrell (pers. comm., August 2, 1995), when his father, Magnus, would perform as a Mock...