![]()

IV

JOKER THEORY

![]()

RICTUS GRINS AND GLASGOW SMILES

The Joker as Satirical Discourse

JOHAN NILSSON

Introduction: The Clown Prince of Crime

The Joker is often understood as Batman’s antithesis, as the yang to his yin, as the agent of chaos that threatens his need for order. Thus, while they function as opposites, they are also intrinsically tied to each other. Indeed, according to Marc DiPaolo, each Batman villain functions as a reflection on the Dark Knight and “they frequently parody or pervert his intentions and method of operation.”1 In the case of the Clown Prince of Crime, Batman’s “true” nemesis, this function is especially relevant, but, as I argue in this essay, it can be taken even further. For DiPaolo, the Joker is a particular kind of commentary on Batman, one that essentially derives from the characters’ antithetical logics (e.g., order vs. chaos).2 However, as this essay will show, the Joker is not only a counter to Batman, but a satirical figure in which a subversive attitude towards contemporary society is realized.

In this role, the Joker-figure’s origin and history is clearly referenced. Joker—fool, prankster, jester, trickster, clown; the derivations of the fool archetype are many, but joining them together is a sense of mischief and a ridicule of authority. In the many incarnations of the Joker, these characteristics vary considerably in both degree and force, making the character quite versatile. There is, for example, a significant difference in tone between Cesar Romero’s comic Joker of the campy 1960s Batman television series3 and film,4 and Heath Ledger’s portrayal of a sardonic psychopath in The Dark Knight.5 Also, like the medieval fool, the Joker wears motley, bright-colored clothes and manifests the carnivalesque by ridiculing dominant ideology and authority, but unlike him, he is not a licensed fool. Fools, Mikhail Bakhtin tells us, were permanent and legitimate bearers of the carnivalesque, that principle (and literary mode) which sees social hierarchies overturned, much like they were in the medieval carnival.6 As such they share many characteristics with satire.

In a film context, satire has resurfaced as a significant mode of expression since the late 1980s, although it really came into its own during the 1990s thanks to a partial merging of independent cinema and Hollywood.7 Going even further, Paul Simpson has argued that “satirical discourse suffuses the general humor resources of modern societies and cultures. It is not an alien form of humor, not something remote from everyday social interaction, but is as much part of the communicative competence of adult participants as puns, jokes and funny stories.”8 Satire has become a form that is part of the (everyday) media logic and that many of us appreciate. It should still be acknowledged, however, that it remains a somewhat ambiguous form in that its various incarnations differ in how easily they are identified as satire. This derives from the fact that satire is formally and thematically diverse.9 Still, satire can be defined as a form that offers ways of resisting dominant ideology by ridiculing power and authority.10 Further, its ridicule is usually constructed by devices such as irony and parody.11 Also, according to Kathryn Hume, works described as satires have become more diverse, and satire often employs fantasy elements in interaction with irony, and it is sometimes identified by such fugitive qualities as tone or flavor.12 The present essay takes this definition as a starting point in terms of analyzing the Joker as satire.

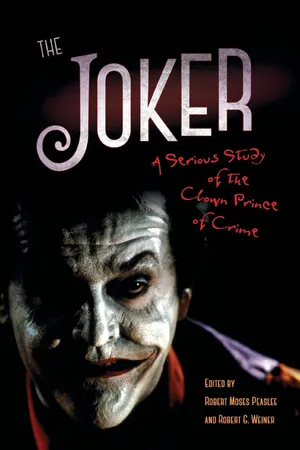

I look at three versions of the Joker; two of them filmic incarnations and one a comic book representation.13 This essay does not make a point of the distinctions between comics and film. Instead, the focus is on the Joker as a character used to deliver satire, the rationale being that the satiric force invested in the Joker is not media-dependent. Even though the construction of satire may differ slightly depending on the medium’s available devices, it always uses some version of irony and some kind of reference to social or cultural issues.14 In Frank Miller’s hugely influential Batman story The Dark Knight Returns (hereafter referred to as TDKR), the Joker is quite subdued (at least in the sequence analyzed below).15 We get internal dialogue that gives us insight into his psyche but relatively few smiles. In contrast, the Joker of Tim Burton’s gothic Batman from 1989, played by Jack Nicholson, leans towards the ridiculous, dancing and cavorting while constantly laughing. He is a clown and a prankster, using popular events (such as a parade), novelties, and household products to perform his deadly visual gags.16 The Dark Knight (hereafter referred to as TDK), finally, features a truly chaotic Joker who is more related to Miller’s than to Burton’s, and of the three he is the one who is the most indirect in terms of satire.

Arguing for a conception of the Joker as a satirical figure requires a firm base in the actual utilization of the character within the “text,” as well as a constructive and pragmatic way of establishing links to discourses actualized by it. Simpson has developed a model for understanding and analyzing satire that is appropriate in this case.17

Satire

Satire, according to Simpson, is a discursive practice and it functions as “a higher-order discourse,” meaning that it exists on a level above genre.18 A similar view can be found in the common practice of regarding satire as a mode rather than a genre. This view is based on the fact that satire shows great formal and thematic variety, that it tends to borrow conventions to the extent that it could be regarded as pre-generic.19 It also derives from particular institutions and the beliefs and knowledge which exist within these institutions in a particular culture, and from the perception that the satirist dislikes some aspect of society.20 This means that the production culture that produces a satirical text is important in that we in that culture find norms, conventions, and specific modes of production.

Satire is made visible in a kind of interactive event where a viewer/reader recognizes the satirical intent by picking up on the text’s references to phenomena beyond itself. For Simpson, this entails an echoing of another discourse event and thus invoking a particular context for the viewer/reader. The actual element within the text that has this function is called a prime.21 In other words, the prime provides the viewer/reader with information about which discourse the satire positions itself within. A second text element, the dialectic, exists in opposition to the prime, and unlike the latter (which is inter-discursive) it is text-internal. The dialectic is to be understood as an antithesis (in a Popperian sense), thus signifying opposition or contrast. It is mainly in this contrasting dialectic that we find the irony that is so crucial to satire. We can thus speak about it as taking on the form of an ironic shift, meaning that the discourse that has been brought to the viewer’s/reader’s attention through the prime is suddenly viewed from a skewed position.22 Let us turn to an example. In discussing the frequent use of news bulletins in Miller’s and Lynn Varley’s sequel to TDKR, The Dark Knight Strikes Again (hereafter referred to as TDKSA),23 Graham J. Murphy has noted that “caricaturized (and superficial) media figures frenetically switch from one story to the next with neither critical insight nor debate.”24 We can thus say that the news bulletins that inform the story actualize a news/media discourse. The added fact that several of these newscasters are naked women skews our perception, which allows us to interpret the satirical intent with the representation: to criticize the sensationalistic and capitalist logic of contemporary news, but also, as Murphy argues, the sexualization of popular media.25 Satire, in short, emerges through a process where a discursive realignment (by way of irony) is occurring.

The Joker, I argue, is a fundamentally ironic figure. He is contradictory, much like the figure of the wise fool—in which “wisdom and folly confront each other,” thus allowing for sustained irony.26 This means that irony takes on particular significance because the Joker is a very tragic (although sympathetic identification differs between various representations) and violent figure at a psychological level, but he wears the face of comedy. It is in this dialectic between these two traits, the psychological and the superficial, that we find the Joker’s potential as a vehicle for satire.

The Dark Knight Returns

Murphy holds that “the political and social critique of the Dark Knight arc (TDKR and TDKSA) is diverse,” and its targets include the emptiness of American mythology, the retracting of civil liberties, and the “misogynistic sexualization of popular media.”27 However, despite its diverse critique, I focus solely on that which is expressed by and through the Joker, who in this story is declared a victim of Batman’s psychosis, which supposedly stems from sexual repression. Declared sane and released from Arkham Asylum, he appears on a thinly disguised simulacrum of NBC’s Late Night with David Letterman,28 where he ends up killing the host, his own therapist, another guest (whose mantra is appropriately Freudian: “Zex und zex und zex”), and the entire audience.29

The sequence echoes psychoanalytic discourse, but repositions it by presenting it in a popular setting. This is done on two “levels”: the representation of popular late-night programming and the fact that the representation occurs in a popular medium (comic book). We can thus argue that the prime in this instance is centered on the popularization of psychoanalysis. In order for satire to be possible, however, the second main structural element needs to be established. The dialectic component becomes apparent when taking into account the way the sequence is positioned within the book. There are two parallel actions occurring over nine pages, the one already mentioned and another one featuring Batman trying to fight through a force of policemen, led by Police Commissioner Yindel, who is convinced the Dark Knight is a public menace, on the roof of the building where the TV show is being taped. The irony is that the ostensibly reformed Joker is accepted into the popular limelight of television, where he kills 206 people, while the publically shunned Batman, in an attempt to reach the former, “only” puts twelve of the cops “protecting” the Joker from him in the hospital. The oppositional relationship between these two actions plays off the already established oppositional relationship between Batman and the Joker. Also, what we see here is an example of historical irony, which we can define as dealing with the historical mistake, or when an individual’s or group’s decision or action turns out to have unintended oppositional effects.30 In the case of TDKR, the Joker has been embraced by both the media and the public, so when he turns on them the irony is cutting.

The Joker is construed as a victim of Batman by a representative and practitioner of psychoanalysis, who seems more interested in appearing on TV than of actually helping his patients. The twist, then, is that the satirical target is not psychoanalysis, but the popularization of it in the contemporary media culture. One could perhaps argue that it is the actual popularization that is targeted, that it brings with it a debasement of knowledge and a tendency to only see the superficial aspects of psychoanalysis (sex and sex and sex), thereby making popularization a threat to its established status as a science.31 However, it seems more likely that the critique is directed at popular media culture in general (the fact that shots of television screens featuring a variety of media personalities are interspersed throughout the narrative supports this argument). The 1980s did, after all, introduce the increasingly commercialized age of cable and satellite television. In fact, televised media is referenced satirically throughout the TDKR narrative (just as it is in TDKSA), often in the form of panels showing news anchors and various media pundits. Of course, media critique is not reserved for this particular story alone, even though we can s...