![]()

Section IV

Drawing History, Visualizing World Politics

![]()

12. Overtaken by Further Developments: The Form of History in Footnotes in Gaza

Ben Owen

A journalist asked Joe Sacco why his book Footnotes in Gaza, ostensibly about two massacres that took place in 1956, gave so much space to accounts of housing demolitions in the Gazan city of Rafah in 2003. Sacco replied that he thought the 2003 events were worth recording in their own right, but also said that he wanted to show how, for Palestinians in Gaza, “events are continuous.”1 By this he meant that people whose experiences since 1948 consist primarily of violent deferrals and defeats “can never look back at 1948 and just think about that. There is no closure.”2 Footnotes in Gaza is Sacco’s attempt to convey the Palestinian experience of resolution’s absence, of each new injury immediately recalling numerous other injuries. In doing so, Footnotes recreates a sense of time unfamiliar to many of his European and North American readers, in which events are not given a strict linear sequence because their importance seems continuously present.

As several critics have observed, Sacco’s work amounts to a kind of ethical witnessing, in which he draws the suffering of people in terrible situations, but also tries to think through the trickiness of his own role as a journalist, a cartoonist, and a Westerner potentially implicated in that suffering.3 I argue that Sacco’s emphasis on different ways of experiencing time, and on the related conflicts between different ways of describing history, is a major part of his work as a witness. The idea that the choices we make about how to narrate history can have profound ethical effects is certainly not new. But it is also an idea that can seem abstract. Part of the value of Sacco’s work is that it provides a detailed and particular account of the human cost of describing history in one narrative mode versus another. Whose history to draw, and how to draw it, are live questions throughout the book, and are plainly visible when a Palestinian father, angry that Sacco insists on asking about 1956 when there are fresh Israeli bullets in his wall, yells, “Every day here is ’56!”4

In the first part of this essay, I show how Footnotes presents several different modes of narrating history, focusing on the conflict between two different modes, the progressive and the cyclical. Sacco offers a pointed critique of progressive, linear history throughout the book, showing both how it fails as a way to describe Palestinian history, and how it is implicated in the relegation of that history to “footnotes.” Instead, his book attempts to depict Palestinian ways of telling history, which are necessarily less cleanly linear, and it is here that Sacco’s use of the comics medium is of particular importance. As Hillary Chute writes, “comics can address itself powerfully to historical and life narrative,” in part because of its “ability to use the space of the page to interlace or overlay different temporalities, to place pressure on linearity and conventional notions of sequence, causality, and progression.”5 Sacco uses this ability of comics in a particularly pointed way, continually using the page to make different historical moments butt up against one another, showing the resonances between them.

But although Sacco presents the nonlinear view of history as truer to the lived experiences of at least some Palestinians, he does not make them fully his own. While Sacco represents the stories of Palestinians who see history as essentially cyclical—a series of inevitable defeats—his own project resists that premise by its insistence on the specificity of 1956 and of 2003. The past is fundamentally not an interchangeable series of catastrophes, even if those catastrophes do echo one another. In asserting this, Sacco tries to maintain openness to different ways of narrating events. This openness is most apparent in the ambiguous interlude to Footnotes, “Feast,” which juxtaposes a time of Palestinian ritual—the feast of Eid Al-Adha—with the lead-up to the American invasion of Iraq.

The value of Footnotes’s specific historical project—to provide a fuller account of the Khan Younis and Rafah massacres—is substantial in itself. But the value of Sacco’s work beyond Palestinian history is, in part, as a model for a kind of popular history that can accommodate itself to telling the stories of places where the dominant modes of history—of progress, of decline—are not adequate to the task. In the second part of my argument, I consider Sacco’s method of juxtaposing conflicting ways of telling history as characteristic of the current trend in comics, particularly in book-length comics, towards difficult, contested, and forgotten history.

Beginning with Joseph Witek’s seminal Comic Books as History, critics have tended to view the suitability of comics for historical subjects as a formal property of the medium.6 So, for example, comics are good at doing history because of their arrangement of different chronologies on the page, either in separate panels or through the combination of retrospective verbal narration and “present-tense” pictures. While this medium-specific approach has led to a great deal of useful work, critics have paid much less attention to the ways in which changes within the way comics are created, sold, and read—particularly the shift towards the book-length comic as a standard form—have shaped how comics address historical subjects. My interest in the specificity not just of comics as a medium, but in the distinctions among different kinds of comics traditions, aligns my work with the scholarship of critics such as Bart Beaty, Rebecca Wanzo, and Henry Jenkins in making the history of particular cartoonists and comics more central to thinking about what does and does not define comics as a medium.7 Some of the most significant criticism on the profound differences between book-length comics, comic strips, and comic books has tended to come from cartoonists themselves. To take perhaps the most well-known example, it is easy to see much of Chris Ware’s work as an extended meditation on the relationship between comics’ different historical forms and other kinds of history—among them, personal, architectural, and metropolitan. This kind of work ought to serve as a guide to comics scholars and critics.

My general claim is that the book-length comic (whether or not “graphic novel” is a suitable name for it) ought to be understood as a more particular object of study, distinct from other kinds of comics. My specific argument is that the sophistication with which book-length comics show stories about contested or contradictory histories is partly the result of the fact that the artists who create them are conflicted about the recent history of comics. Footnotes in Gaza is a good example of this because it is not explicitly about comics at all, and yet its most conspicuous formal experiment—the three-and-half-page wordless coda—relies on a discrepancy between the kind of self-contained short story typical of the pamphlet-format comic book anthologies Sacco worked on for most of his early career, and the meticulous long-form narrative of the rest of the book. I do not mean to suggest that Footnotes is secretly about comics history, but rather that it uses the tension between different forms of comics as a structuring metaphor for the difficulty of drawing a story based on eyewitness testimony that is both an accurate account of what happened and a faithful record of the emotional experience of those witnesses.

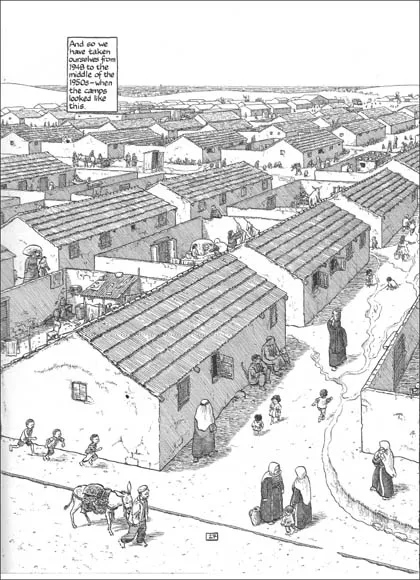

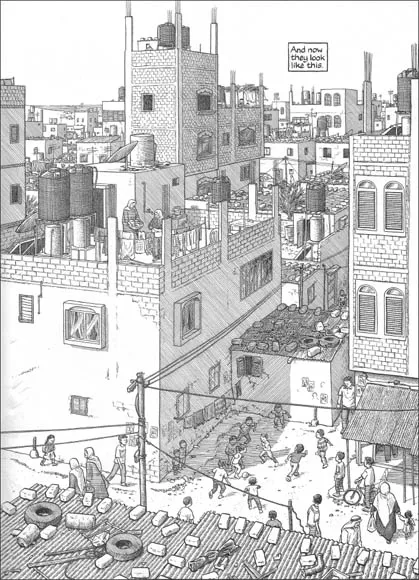

Historical Time and Footnotes in Gaza

Footnotes in Gaza mocks the idea of historical progress. It does this in a number of ways, but perhaps the most striking is Sacco’s juxtaposition of two pictures of Khan Younis refugee camp in Gaza, past and present. The pair of full-bleed splashes in Figure 12.1 show the same view of the camp at two different times: the first in the mid 1950s, and the second in the early 2000s. They conclude an account of the flight of Palestinian refugees to Gaza in 1948, which Sacco draws based on the testimonies of elderly Palestinians whose families fled the fighting between Israelis and the Arab armies, or who were expelled from their homes by Israeli forces. Narration in captions explains the comparison between the two pictures of the camp. In the upper left corner of the first page in Figure 12.1 are the words: “And so we have taken ourselves from 1948 to the middle of the 1950s—when the camps looked like this.” And on the final page in Figure 12.2, in the upper right corner: “And now they look like this.” In the first picture, we see regular blocks of identical single-story brick houses (the preceding pages have explained that these brick houses replaced the clay houses that preceded them; which, in turn, replaced UNWRA and Quaker-supplied tents; which replaced the shelters of branches, dugout pits, and blankets that the refugees first constructed in 1948). In the second picture, we see a dense sprawl of three- and four-story buildings, their top floors generally unfinished.

Figure 12.1. Joe Sacco, Footnotes in Gaza (New York: Metropolitan, 2009), 27.

Figure 12.2. Joe Sacco, Footnotes in Gaza (New York: Metropolitan, 2009), 29.

What is arresting about the two pictures (and Sacco’s other diptych showing the scene of the Khan Younis massacre on the day of its occurrence in 1956, and again in late 2002) is that their angles of view are identical, though temporally separated by almost half a century.8 Because the buildings have changed so much, the use of identical perspective and framing encourages the reader to see similarities that might otherwise escape attention. It is perhaps a small shock to realize, gradually, that this is the same corner of the same street. The sense of similarity is reinforced by the fact that the identically framed images in Figures 12.1 and 12.2 are both on the right-hand page, meaning that the drawing of the mid-50s scene physically overlays the drawing of the early 2000s.

The identical perspective and the meticulous detail parody the form of an architect’s “before and after” drawing, particularly those in which a semi-transparent sheet can be laid over the “before” image to show what will happen “after.” Sacco’s images challenge the architect’s presentation of progress through construction. The story of steady improvement, which functions as one of the default modes for structuring history in Europe and America, does not apply to Gaza. At the most simple level, we see this argument in the fact that it is very difficult to read the state of the camp in the 2000s as an obvious improvement. The unpaved streets of the 1950s are still unpaved. Many of the kids in the later picture do not have shoes, just like their parents and grandparents in the earlier picture. The material accumulation depicted in the later picture—additional floors to the buildings, telephone wires, water heaters, and satellite dishes—may be interpreted as progress, but might also appear as part of the increase of flotsam and junk, kin to the bricks and old tires laid down on corrugated iron roofs to prevent them blowing away. Indeed, the inspiration for these pages could come from either Walter Benjamin or R. Crumb.

Benjamin’s figure of the angel of history from his cryptic late work “Theses on the Concept of History” is useful for understanding this scene because it is attuned to the idea of history as a perpetual disaster that Sacco finds in Gaza: “Where a chain of events appears before us, he [the angel] sees one single catastrophe, which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it at his feet.”9 In Sacco’s image of Khan Younis, the piling of the wreckage is rendered literal. Events do not move on in a linear chain, but rather accumulate. Where in other places refugees might have moved on, allowing for the maintenance of an idea of progress, “Khan Younis camp has had nowhere to build but into the streets and up.”10 The pages also appear to consciously echo that of his most direct influence as a cartoonist, Crumb, particularly the 1979 comic strip “A Short History of America,” in which overhead wires, concrete, and what Crumb regards ...