![]()

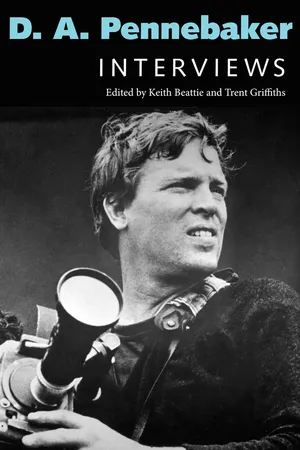

D. A. Pennebaker

G. Roy Levin / 1970

Interview conducted September 2, 1970, in D. A. Pennebaker’s office in New York City. From Documentary Explorations: 15 Interviews with Film-Makers (Anchor Press, Doubleday and Company, 1971). Reprinted with permission of Jordan Levin, Bryna Levin, Maurie Levin, and G. Roy Levin’s Estate.

G. Roy Levin: On the phone you said that you don’t make documentary films.

D. A. Pennebaker: Well, I try not to. I can’t help it if you call it that. I mean, if somebody paid me, I’d just make anything. You know, just a working man.

GRL: You’re willing to make any kind of film? You really don’t care at all?

DAP: That’s what I’m told by everybody else.

GRL: I don’t believe that.

DAP: You do what you’re told. You want to see documentary films, somebody pays you to do it, right?

GRL: There aren’t any films that you want to make?

DAP: Oh sure. God, yes. But when you work here, you work. If you’re a cameraman or a filmmaker, you’re committed to making films people want to pay for, most of the time. I’ve got seven or eight films in the back room. Hour-length, hour-and-a-half, half-hour-length films that I can’t sell to anybody. What does that prove? That I’m virtuous? That I know something nobody else does?

GRL: What kind of films are they?

DAP: Oh, they’re just films about people, but they don’t have any particular form to them. A film of Jack Elliot and people like that. I made it in a nightclub one night with Janis and some people singing in there.

GRL: Janis Joplin?

DAP: Yeah. They’re not documentaries. They weren’t intended to be documentaries, but they’re records of some moment. I’ve got a film I made in Russia, a film I made of the eclipse. They’re just films that I made because something happened that interested me, but I can’t make a living off these kind of films. Not for a minute. But I don’t call them documentary films. When people come to me, they’ve already got a sense of what they want to call the film they want me to make. If they want to call it documentary film, that’s their problem.

My definition of a documentary film is a film that decides you don’t know enough about something, whatever it is, psychology or the tip of South America. Some guy goes there and says, “Holy shit, I know about this and nobody else does, so I’m going to make a film about it.” Gives him something to do. And he usually persuades somebody to put up the money who thinks this is the thing to do. Then you have the situation where this thing is shouting on the wall about how you don’t know something. Well, I think that’s a drag. Right away it puts me off. There are a lot of things I don’t know about, but I can’t stand having someone telling me that. That’s what the networks do: “Ah, you don’t know about dope. We’re going to tell you about dope today. Here is an interview with Mrs. Jones. She knows about dope.” And Mrs. Jones, gee, she’s a billion people around—I mean, how can one or ten or even five hundred people know really what’s going on? Then five minutes later it’s all changed anyway. So the whole basis for this kind of reporting is false. It pretends to be reporting but it isn’t, most of the time.

On the other hand, it’s possible to go to a situation and simply film what you see there, what happens there, what goes on, and let everybody decide whether it tells them about any of these things. But you don’t have to label them, you don’t have to have the narration to instruct you so you can be sure and understand that it’s good for you to learn. You don’t need any of that shit. When you take off the narration, people say, “Well, it’s not documentary anymore.” That’s all right, that’s their problem. That’s why I say that films that interest me to do, I wouldn’t consider documentaries.

If I was going to make a film on dope, let’s say, if I made one this week, it might say one thing. If I made it next week, it might be quite different. But you couldn’t call that documentary film. It’s not very analytical. I don’t know what it is, but I’ve got to be absolutely prepared that that’s the way it’s going to go, that there isn’t a thing to say about dope that’s going to be universal and I’m the one that’s got the message to do it. So you pay me a little money and you tap me on the shoulder and I’m blessed. And I get to do it. Ah, that’s bullshit. I don’t trust people just because they have a camera. I don’t even trust people who write books, and that’s a lot harder than shooting a camera.

GRL: You spent a long time working with [Robert] Drew. How long?

DAP: Two or three years. That’s not a long time. A long time just getting into the camera.

GRL: In that time, were the films you made what most people would call documentary?

DAP: They are half and half. They are kind of half soap opera, half documentary. The part that interests me, that I like about them, is the soap opera, I suspect. The parts where they failed are probably as documentaries. They probably weren’t quite objective. I don’t know, they were different. Which ones have you seen?

GRL: The Chair, Susan Starr, Football, the one—

DAP: Football is, I’d say, one of the good documentaries. Yanki No! is a good documentary. They were good documentaries in that they had a measure of unpredictability and life that made them interesting, just as I guess Target for Tonight [Harry Watt, 1941] was documentary and so was Night Mail [Basil Wright and Harry Watt, 1936]. But there was a kind of freshness and excitement in them that pulled them out of that, so you remember them. You don’t remember them for their marvelous insights into the mail service or anything; you remember them for their poetry, or whatever it is. I think that The Chair is abominably edited, that it was reduced to a kind of straight-line plot analysis when in fact what is most interesting about the story in the film was the people involved, the characters, and the problem was they kept shifting their positions; these were people who were supposedly guided by the majesty of the law, who supposedly proceeded straightforward, but they didn’t, they jumped around. Well, we ended up with just a rinky-dink plot, and in the end nobody remembers a thing—but Drew was always persuaded that the plot carried. He edited it, actually. Ricky [Leacock] and I shot it, but we were out on something else when it got edited; when we saw it later, we were both quite shocked.

As for Crisis, I think part of it was badly edited and part of it was marvelously edited. And it makes a difference; the halfway point in that film is fantastic. The first half is sort of a paean to Kennedy—it has a statue of Lincoln; it was just filled with the worst kind of prosaic, predictable bullshit. The second half was marvelous. Ricky sat down—I’d quit by then, kind of over that film—and found both ends of the telephone conversations. It really opened up. So in fact there is a great deal to be learned by looking at it. There’s nothing to be learned from the first half, it simply summarized your position.

I just glanced at something on television the other day. CBS is doing something on Africa. First the cat goes down there, he gets off the plane, he’s in Africa, right? He’s going to dig black faces and bizarre things. He’s got his camera out and there’s a guy doing traffic. In any English place or most of the East, traffic is a marvelous thing. Well, the cat gets carried away, so for the first four minutes some cute editor in New York decides this is a wonderful insight, and it’s bullshit. So we’re all treated to what some editor and some cameraman—neither of whom know anything really, about Africa or about anything, other than to get the film into a bag—take a cute shot. Well, in the end, you just have to think, if they’re looking at the wrong things, where are the right things? How do you see the right things? And who is doing that? You never see it in documentaries, so I don’t know. I’m actually more interested in somebody’s bullshit Hollywood film. At least when I go see it, nobody’s bullshitting me. They’re doing what they know how to do, and most of the time it’s boring too, in a sense, except if the story happens to be good or if it’s just the animal, simple thing, at last you see something that’s alive. I can’t stand dead films, I guess. And my sense is that most documentaries, by their very nature, the minute they’re conceived, become dead.

GRL: Are there any documentary filmmakers that you like?

DAP: I don’t know what you call documentary filmmakers. I was quite surprised, in fact I was knocked out when I saw Warrendale, because I’d seen some films that Al [King] had done before, and I thought they were terrible. They used to be dead alligators lying there, perfectly exposed and set. But in Warrendale he had the wit to see that it was drama and to go for the drama and get that. He isn’t a cameraman. I was surprised, because normally I can hardly conceive of anybody making a film without a camera. I mean, what is it you do? It’s an easy thing to say, but it means that later he just picks up and kind of summarizes somebody else’s intuitions. It’s like two people painting a picture. I’m sure you could do it if that’s the way it had to be done, but it seems a strange and incredible way to do it, and it’s hard for me to imagine it coming out. Well, he did it. Warrendale is an honest film. It’s not the greatest film ever made.

In a way it doesn’t have anything like the excitement of Target for Tonight, which I’m sure is fake. It was all shot in a studio, though some of it in planes, but everybody doing lines. They’re all actors. But it had a kind of excitement, because at the time everybody was going to war, or because the people who did it, Grierson, or whoever was pushing the buttons on the thing, they had a kind of excitement. I don’t care whether it comes from real people reciting lines or actors reciting lines. Lines are lines.

GRL: Have you ever seen The Battle of San Pietro?

DAP: Sure. A Huston film. It’s a good film, although if you see it a lot of times you realize what a total amount of fakery went on in the editing of it. He’s using shots from all over the place, so it isn’t really … It looks on first viewing, or second viewing, to be just some cat with a camera watching everything go to pieces, but in fact it’s incredibly put together, and after you’ve looked at it a lot of times, and I have, you begin to see the cheating that took place in the editing. But you accept that because you know that Huston came out of that kind of filmmaking, and to him that wasn’t cheating. Only cheating let’s say to Al Maysles, who thinks it’s cheating—but that doesn’t make it cheating. Of course, the film is going to be here a hell of a lot longer than Al Maysles is, so in the end, cheating is a misnomer. But if I was going to make a battle film, I wouldn’t do those things. I’d be afraid to. That’s because everybody is smarter now, but it took that film to get us smarter, so it doesn’t take anything away from the film. In fact, it gives something to it because the evolution had to be toward more truth, not less. And if that was true, how do you get more truth? Well, you find out what in it could be more true, and that takes looking and thinking, so that it does a lot of work. Just as another Huston film did, Let There Be Light, the one about shell-shocked soldiers. That’s probably got less contrived editing.

GRL: I’ve seen both of them only once, and on first viewing it seemed to me to be the opposite, that Let There Be Light is more gimmicked up.

DAP: Maybe it is. I’ve only seen Let There Be Light once, a long time ago, and it’s fuzzy in my mind. San Pietro I looked at a lot because it has a lot of vitality to it, a lot of excitement, and he throws away a lot of form—and that passes for excitement too. If that film were made now, it would create a lot of excitement. That’s as up to date a film as is being shot around now. There’s nothing around now that’s as well done as that.

GRL: I’ve looked at a good number of the wartime documentaries, and a lot of them were really well made, exciting in the editing, but they were often offensive, infuriating, because they were so chauvinistic.

DAP: Actually I have a lot of Signal Corps films. They didn’t even bother to do that. They just show endless landings. Of course, the great final travesty on all war films is the film that wasn’t about any war at all, which was Victory at Sea. It was just stock shots, it was the thing that NBC did on television. A thirty-two-hour show with that mellifluous voice of what’s-his-name? The guy, the announcer. Well, you know, he’s got the terrible, very English accent, and he’s announcing all these battle scenes. Then there’s a shot, there’s just long, black cannons shooting at each other. Everything could be anything. It gives you a terrible feeling that there was no war at all. It’s all somehow out-takes, and edited versions. I never sensed I was in a place when they told me I was in a place. I’m sure somebody tried to—they must have. There are some pictures from Kwajalein, but in the end it didn’t matter. That’s what’s fearful. You could have taken Kwajalein and put it with Tinian and nobody would have cared. It was just people doing the same thing in the same shot to the same music. It was just an endless kind of tapestry of no place, no time.

GRL: That kind of thing seems most dangerous to me in television documentaries where it’s done in part by the voiceover commentary that changes the sense of what you see.

DAP: Scourby. Did you know Alexander Scourby? He does some Band-Aid commercial now. I can just hear him saying, “Three hundred fifty thousand were killed at Tarawa Beach,” you know, but with this kind of meticulous accent like a man selling you a brooch at Tiffany’s. Terrifying. So out of sorts with what he’s talking about. But it didn’t bother anybody. People just accepted it—“That’s nice.” Somehow it upgrades war. Sort of makes it a noble enterprise, I guess.

GRL: What I liked about San Pietro, contrary to all those others that were so harsh and chauvinistic and shrill, is that there’s a humanity there.

DAP: Yeah, that’s true, but the thing about San Pietro—and this is my personal feeling—is that all those things are his style. He’s one of the great stylists. People, I think, make the wrong assumptions about Huston. Most of the time I don’t think he is a very good storyteller. He has the reputation for being a goo...