![]()

1

Foundations of the Botánica

“I’m a Catholic and I go to Mass. It means a lot to me but it’s a religion of the ear. The orishas are the religion of my heart. I put them both together and it helps me grow as a person.”

Teresa, patron at Botánica La Sirene, San Francisco

Teresa’s participation in multiple and layered spiritual traditions reflects the religious experience of many Latinos in the United States. Each region of Latin America has its own herbal and healing traditions, its own pantheon of saints and heroes, and its own organization of its indigenous, European, African, and Asian heritages. These have become reblended and juxtaposed in the United States, making botánicas highly pluralist spiritual sites. Yet depending on the backgrounds and inclinations of the botánica owners and clientele, a store will feature some traditions more than others. Botánicas in California, for example, are more likely to highlight Mexican traditions like the Virgin of Guadalupe and La Santa Muerte, while a store in New York might be centered on Dominican devotions such as Papa Candelo or Anaisa Pie. Yet different communities are in contact and often communion with others, and so tradition is layered upon tradition in ways that are seen by practitioners to be mutually enhancing.

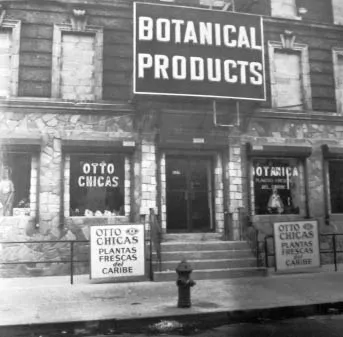

An old photo of Botanical Gardens/Otto Chicas store, courtesy of Otto Chicas.

Amid this diversity and eclecticism, however, there are certain cultural and religious bases that most botánicas share. The origin of the institution in its present form is almost certainly Latin Caribbean and arises in the mixture of cultures in the City of New York. The first botánica to be so called was documented in 1942 by Rómulo Lachatañeré, a Cuban living in New York with the apt qualifications of pharmacist and ethnographer. Lachatañeré had studied African-derived religious traditions in his native Cuba, and he was struck by their presence at a store called Botanical Gardens in East Harlem. The neighborhood, he said, “seems like a Puerto Rican city, but there are lots of Cubans, Dominicans and people from all over Hispanoamérica.” He saw the store as “a factor of importance in the life of the Spanish-speaking community of the barrio of Harlem,” and he recognized in it something of the Latin Caribbean spiritual world in North America.1 The Botanical Gardens shop reminded him of the Caribbean, or as he prefers to say, “Antillean” stores called boticas, small folk pharmacies that sell herbal and magical remedies. He writes:

Herb stall, Calle Moncada, Santiago, Cuba, 2001.

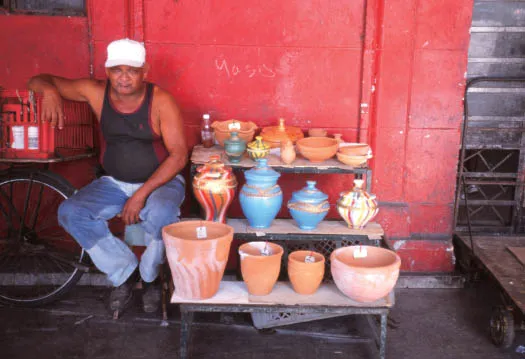

Man selling iron and candles for the orishas, Calle Moncada, Santiago, Cuba, 2001.

Undoubtedly the “Botanical Gardens” shows an aspect of the religious life of Antilleans that we observe in Harlem. It expresses the cross between the botica of the islands and the North American drug store. It constitutes the acculturation of the botica that is popular everywhere in the Antilles. In these boticas, the pharmacists have to study in depth not only of the scientific but the magical properties of medical herbs that are activated by supernatural forces . . . they have to know the formulae of incantation in order to, for example, arouse or kill sexual powers . . . and there must be cooperation with curanderos [healers] if they are not healers themselves, and with those who are called, often inexactly, brujos and brujas sorcerers.2

Man selling orisha pots, Havana, 2001.

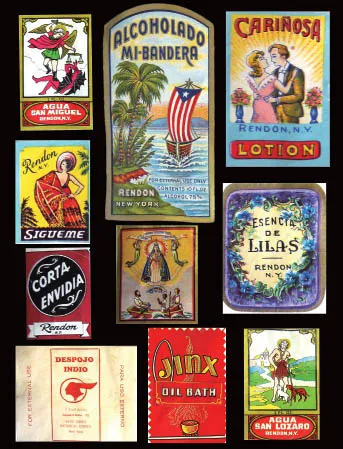

Rendon herbal preparations.

The Botanical Gardens was already something of a Harlem institution when Lachatañeré came across it in the 1940s. It had been founded some twenty years earlier by a Guatemalan herbalist named Alberto Rendon. The New York Times noted his passing in 1979 and said his customers considered him “the class of the barrio’s flourishing botanica trade, offering fair prices, tracking the most exotic customer requests, devising himself some of the more powerful elixirs, to stir life’s love and good fortune and to hold off an enemy’s ill will.”3 According to Migene Gonzalez-Wippler, the store originally catered to English-speaking West Indians and African Americans seeking fresh herbs, but in the 1940s “they were soon vastly outnumbered by the large numbers of Puerto Ricans clamoring for spiritual relief from their problems of adaptation to their new homes.”4 It was the store’s Puerto Rican customers, says Gonzalez-Wippler, who shortened the name to La Botánica, and the name stuck as a generic term for the unique institution now found in Latino neighborhoods throughout the United States.5 The Botanical Gardens store survives today in East Harlem, where it is known as La Casa de las Velas (The House of Candles) and is run by Rendon’s nephew, Otto Chicas, and his wife, Rosa Chicas.

The Botanical Gardens/Otto Chicas store in 2011.

Carolyn Morrow Long has documented the history of “spiritual merchants” in the United States, beginning with African American root doctors and seers in the South of the nineteenth century. By the early twentieth century, “hoodoo drugstores” prepared remedies for those seeking help with love, money, health, and all the new challenges of urban life. In those days before federal regulations, pharmacies sold all manner of remedies and ingredients important in charm making such as alum, saltpeter, and laundry blue. In spite of professionalization, a few pharmacists continued to make magical preparations, but the bulk of the “hoodoo” market was taken up by entrepreneurs. Long cites the famous study of 1930s Black Chicago by Saint Clair Drake and Horace Clayton that spoke of hundreds of “spiritual advisors” on the city’s South Side. Notable among them was Professor Edward Lowe, astro-numerologist, whose store sold “policy numbers, roots and herbs, lodestones, oils, and occult texts such as the Sixth and Seventh Books of Moses.”6 In the late 1960s, David Winslow created a compelling portrait of Bishop E. E. Everett, who had come to Philadelphia from North Carolina and owned and operated a “spiritual supply store” in Philadelphia.7 A store handout announced:

Everett’s Spiritual Supply Store

All Your Needs

Bishop Everett is a Man of Faith and Power Who Can Help You Regardless of What Your Troubles or Circumstances Are. Since the Opening of His Beautiful Store, Homes Have Been Brought Together, Jobs Have Been Gotten, Evil Has Disappeared From The Shadows Of Many Doorsteps.8

In addition to roots and oils, the bishop sold a great variety of candles and did occult work with them on behalf of his clients. Winslow provides a detailed example of candlework to treat a client in “a crossed condition” involving six different candles carefully juxtaposed, dressed with appropriate oils, and energized with Bible verses over the course of three days. This care to detail and to the health and confidence of his clients led Winslow to conclude about the bishop’s work, “I strongly suspect that his program is bringing more hope, security, satisfaction, and happiness to the ghetto than all the ‘poverty programs’ vainly attempting to solve urban problems.”9

Few of these African American hoodoo drugstores and candle shops are here today; their place taken by botánicas with the waves of Latino migration in the latter part of the twentieth century. Still, an important part of the clientele of contemporary botánicas is African American, and the stores’ continuity with southern herbalism and with the African spiritualities reintroduced to the United States by Latinos make contemporary botánicas appealing to African Americans and Latinos alike. Latinos bring to this herbalist heritage distinctive spiritual traditions that expand its metaphysical array. Among the vast variety of Latin American religious traditions present in the botánica, ubiquitous and nearly universal is what can be called folk Catholicism. This comprehends an assortment of beliefs and practices alongside the official Catholicism taught by the magisterium of the Roman Catholic Church and promulgated by its clergy.10 While the line between “folk” and “official” Catholicism may often be difficult to determine, it might be seen in shaded contrasts in the religious lives of Latin Americans. In his studies of the Yucatan, Robert Redfield spoke of a dynamic interaction between a “great tradition,” brought from Europe by the Spanish and imposed from above by elites, and a “little tradition,” developed by indigenous and creole laypeople that integrated pre-Columbian beliefs and practices with those of the “great tradition.”11 Other observers have recognized a similar dynamic in the religious lives of ordinary people and have posited a distinction between “other-worldly” or “philosophical” religion that is concerned with salvation and the afterlife and “this-worldly” or “practical” religion that seeks remedies for the ordinary problems of life, particularly health in all its senses.12

In addition to its practical orientation, folk Catholicism validates lay authority. It is often led and practiced by women and treats domestic and personal problems that afflict the family. Finally, folk Catholicism is centered much more on devotions to the Virgin and the saints, both canonized and not, rather than to God and Jesus. These devotions are deeply reciprocal, characterized by promesas, vows of offering to the saints in exchange for their help. Most promesas involve external devotions at the shrines of saints, including pilgrimage to sacred sites and the elaboration of home altars. The material expression of devotion to the saints and other spiritual beings is a common thread of ordinary Latin piety and thus of the spirituality of the botánica.13

Toge...