![]()

PART 1

Collecting Folk Music in 1936 and 1939

Folksongs of Mississippi and Their Background

A. P. Hudson’s book Folksongs of Mississippi and Their Background, published in 1936, remains the major collection of folk songs from the state to this day. It also served as a catalyst to the events that added to the documentation of fiddling in Mississippi. The late 1920s and early 1930s had seen the commercial record industry’s efforts in Mississippi accumulate about 185 fiddle recordings from the state. Field collecting in the summers of 1936 and 1939, building on Hudson’s efforts and contacts, documented another 331 fiddle tunes.

Arnold Palmer Hudson (1892–1978) was a Mississippi native, born in Palmer’s Hall in Attala County, Mississippi. As a freshman at the University of Mississippi in 1908, Hudson was inspired by his English teacher Ebner C. Perrow’s interest in collecting folk songs. Perrow at that time was preparing a number of songs for publication in the Journal of American Folklore. However, moving from inspiration to action took fifteen years. Hudson began teaching in the English department of the University of Mississippi in 1920. Three years later, during his English class teaching English and Scottish ballads, one of his students, Wessen M. Crocker, recited several songs. Crocker stated that his cousin, Mrs. G. V. Easley, knew many more. In 1925 Hudson and Crocker visited Mrs. Easley at her farm and collected twenty-five ballad texts. Shortly thereafter two of his students, T. A. Bickerstaff and Lois Womble, collected more texts.

His interest in folk song growing, Hudson gave a lecture, “A Patch of Mississippi Balladry,” during the 1926 summer session at the University of Mississippi, which generated interest and donations of ballads collected by students. Newspaper coverage of the lecture generated “a number of communications from widely scattered sections of the state,”1 including ballad texts.

In the fall, Hudson taught a seminar course in the folklore of Mississippi where his eight students collected several hundred ballads. The following year nine students added about 500 more songs. In the spring of 1927, Hudson founded the Mississippi Folk-Lore Society, which never grew beyond twenty-five members and published only one collection, Specimens of Mississippi Folklore, later largely absorbed into Mississippi Folk Songs and Their Background.

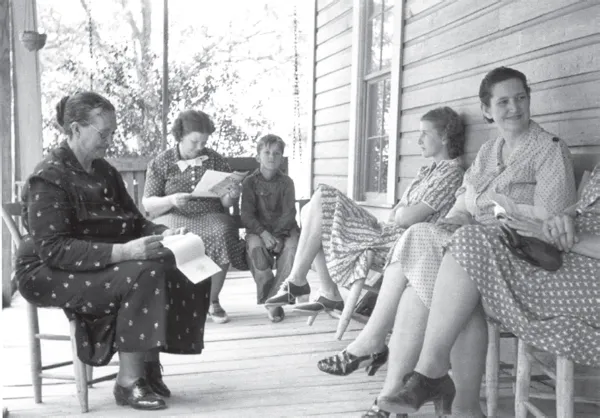

Ballad singers: Mrs. Bickerstaff, Mrs. Lillian Bickerstaff Pennington, Miss Hellums, Mrs. Audrey Hellums, and Miss Eri Douglas, state director, FWP. Tishomingo, May 11, 1939. Photo by Abbott Ferriss, courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

Hudson’s approach to documenting folk song was editorial. Instead of working from primary written sources, as had many previous scholars, he utilized his students to do the bulk of the actual collecting. The focus was primarily on survivals of English balladry among white people in Mississippi.

In his book, Hudson utilizes early census reports to describe the settlers and therefore their music’s cultural origins. He points to patterns of migration to suggest that the bulk of settlers in early Mississippi were of English cultural background, with a small percentage of Scots and even fewer Irish. He traces them as part of the ongoing westward migration starting with the offspring of residents of the well-settled states of Virginia, North and South Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama. He notes the large numbers of slaves but does not factor them into his calculations. He ignores their music as well.

Publishing was certainly on Hudson’s mind in 1927. One hundred pages of “Ballads and Songs from Mississippi” appeared in the Journal of American Folk-Lore (Vol. XXXIX, no. 152, 1927), which also allocated thirteen pages to Harvard’s preeminent folklore scholar, Professor George Lyman Kittredge, discussing two of the songs. The idea of a larger work was forming in Hudson’s mind, and he approached Professor Kittredge about it, writing him: “If Harvard University Press brings out the volume, I am afraid you will have to take my judgment about some little matters of inclusion and exclusion, for in these ballad books (of which Harvard University Press makes something of a specialty) the Syndics rather lean on me.”2

Hudson’s collecting work in Mississippi folklore ended in 1930 when he received his PhD from the University of North Carolina and moved there to teach as associate professor of English.

Ballad singers: Mrs. Mae Wesson, Ila Long, Theodosia Bonnet Long, Birmah Hill Grissom. May 8 or 9, 1939. Photo by Abbott Ferriss, 1939, courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

Due to the financial constraints of the Depression, publication of Folk Songs of Mississippi and Their Background was delayed until 1936, when the University of North Carolina Press published it. The book in its published form contains 157 songs and ballads, many with multiple versions listed, but in text only, without musical notation. Its 321 pages also contain chapters on Mississippi history, ballad communities, and singers. Much attention is paid to aligning the ballads with versions from Francis Child’s epic work of scholarship, The English and Scottish Ballads.

Hudson was well aware of the limitations in publishing a book of folk song without musical notation. In a 1937 letter of advice to a Florida English teacher on how to go about collecting folk song, he said: “If it is at all possible, musical notation of the song or ballad should be secured. Interest in the musical side of folk song is decidedly on the increase.”3 His 1937 publication (with George Herzog, “one of the first scholars to be called an ethnomusicologist”4), Folk Tunes from Mississippi, rather modestly attempted to diminish that failing with its publication of forty-five melodies:

The following folk song tunes were collected from white people in Mississippi between the years of 1923 and 1930. . . . The notations were made by sundry obliging friends and acquaintances, some of whom were trained musicians but most of whom knew only the elements of musical notation. For the merits or shortcomings of the notations I am not qualified to offer either praise or apology. I am uncritically grateful to each and every one of my helpers.5

A young Alan Lomax, then twenty-three years old, wrote a very critical review of Hudson’s Folksongs of Mississippi and Their Backgrounds at the end of 1938, attacking Hudson for his defense of southern class structure where the “privileges of a superior order were more or less conceded.” He further argued that the songs were presented out of social context with no mention of the informant’s poverty or that folk songs were still being made up. Lomax saw folk music is a living tradition, whereas Hudson’s framing of folk as static and ancient reeked of Francis Child’s outdated idealization of the “folk.” A few months after that review, in the summer of 1939, Alan and John Lomax stopped in North Carolina to see A. P. Hudson. They were conducting a courtesy call to inform him that they would be collecting in his “turf” and to ask for his advice and support as they were planning some recording in his area.

That same year, Charles Seeger of the FMP in Washington reviewed the Mississippi music manuscripts collected in 1936, work that was based on songs and contacts from Hudson’s Folksongs of Mississippi and Their Backgrounds. Excited by the richness of that collection, Seeger proposed the summer expedition that recorded Mississippi fiddlers.

Hudson continued to teach folklore and English romantic literature at the University of North Carolina until his retirement. In 1952 he edited (with H. M. Belden) two volumes of the Frank C. Brown Collection of North Carolina Folklore. He edited North Carolina Folklore, the journal of the North Carolina Folklore Society, from 1954 to 1963.

Hudson had the only folk recordings available on campus on a small shelf in his office, which he used to illustrate his course. Admittedly there were few recordings available in the early fifties, but in his class Hudson made no distinction between the recordings of the Kingston Trio, John Jacob Niles, and opera singers performing “folk” as art song or Lomax field recordings of actual ballad singers. A University of North Carolina graduate student in 1953 described attending A. P. Hudson’s course “The English Ballad”: “When he played these pieces in class, Hudson listened as raptly to the over-artful renditions of Dyer-Bennet as to the classic traditional performances of Horton Barker.”6 That grad student, Daniel W. Patterson, took over the ballad course on Hudson’s retirement in 1968 and began building on Hudson’s small shelf of records. Eventually the library at the University of North Carolina became the home of the John Edwards Memorial Collection, one of the premier sources of documentation and recordings for early country music in America. Hudson’s papers and recordings were one of the first folk collection donations to the university.

Roosevelt and the Depression

Everybody in Washington from the Roosevelts on down was interested in folk music . . . They were the first prominent Americans to ever spend any money on it.

—Alan Lomax7

These were tumultuous times. The stock market finally bottomed out on July 8, 1932, after the 1929 crash. Bank closings started in February 1933 in Louisiana and spread to other states. There was increasing panic heading toward the inauguration. Farmers were rioting. All twelve Federal Reserve banks closed. Banks in forty-three states had closed; there was only limited business or restricted banking. President Herbert Hoover did nothing. Eight days after his inauguration, Franklin Delano Roosevelt gave the first of his “fireside” speeches, claiming that there is “Nothing to fear but fear itself” and promising action. The next day, Monday, the banks reopened. America was ready for dramatic changes.

Roosevelt turned to Harry Hopkins, with whom he had worked when governor of New York, for ideas and action to put people back to work. Together they put into place a series of short-term programs to create work, with an alphabet soup of acronyms: NRA, FERA, RS, and CWA. Funding varied wildly from year to year as the administration shifted programs and priorities to navigate the economy and the anti–New Deal opposition.

The Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) was a temporary first attempt to relive the crisis by administering direct relief. But, as Harry Hopkins saw it, there were two major flaws. First, $6.50 per week was not enough money to live on. Second, applying for relief required a humiliating “means test” of providing proof that one was indeed destitute. Hopkins firmly believed, based on his previous relief administration experiences in New York, that most people would rather work than take handouts. Charity abused their dignity, but there is no shame in work. Moreover, workers could retain or develop new skills and the nation could benefit from the results of the work.

Afro-American church gathering. Photo by Abbott Ferriss, 1939, courtesy Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

When the FERA expired unemployment remained high, and along with it the need for government assistance. By executive order Roosevelt then created Works Progress Administration, again headed by Harry Hopkins, who directed that it “shall be responsible to the president for the honest, efficient, speedy and coordinated execution of the work relief program as a whole, and for the execution of that program in such manner as to move from the relief rolls to work on such projects or in private employment the maximum number of persons in the shortest time possible.”8

In the midst of a mighty effort to get America back to work, Roosevelt, in stark contrast with Hoover, found it useful to focus attention on poor whites and minorities that were suffering the most from the Depression. Folk music became one more tool, celebrating the strength and resiliency of the “Forgotten Man” and emphasizing cultural unity and collective action.

Folk music was encouraged in programs throughout the New Deal, but also invited directly into the White House for concerts nine times during the Roosevelts’ time in residence. Alan Lomax was invited by Eleanor to sing privately for Franklin Roosevelt in their home. The high point for New Deal folklorists was the state visit in May 1939 by the King and Queen of England. Charles Seeger was involved in programming of a performance arranged by Eleanor Roosevelt. Marion Anderson, Kate Smith, and Lawrence Tibbett performed classical and light pop. A...