![]()

INTRODUCTION

“I was never one of those people who automatically dismissed genre stuff. I dismissed mysteries because it seemed stupid to read stuff with a solution at the end, like a crossword puzzle, until I actually read some good ones, like Hammett and Chandler. You realize that people can actually do anything within those boundaries.”

—Ed Brubaker (Groth and Spurgeon 73)

As a prolific and talented comic book creator, Ed Brubaker occupies an interesting position in the contemporary comics scene as a self-described pulp writer, devoted to the conventions of superhero and crime stories. He describes himself as such in a time when contemporary comics are now often distanced from their pulp origins by creators who prefer to connect the medium to more culturally approved art and design traditions. In contrast, Brubaker’s work on company-owned properties like Batman and Captain America and creator-owned series like Criminal and Fatale lives up to the traditional expectations for superhero and crime stories, respectively. And yet, as Brubaker acknowledges, he likes to extend genre boundaries and experiment with how far he can extend those boundaries before the genres need to be called something else. Moreover, Brubaker layers his stories with a keen self-awareness, using his expansive knowledge of American comic book history to invigorate his work and challenge the dividing line between low and high art. In this way, Brubaker works not only as a popular entertainer but also as a self-conscious artist and a critical theorist. And while he tends not to refer to himself as a theorist or situate himself within any specific theoretical framework, Brubaker’s work is often described as postmodern by people who may or may not understand the term.

In any case, Brubaker is an artist of intersections and feels comfortable with his position as such. Aside from modernism and postmodernism, some of those intersections to which he blatantly makes reference include the aforementioned pulp and art as well as biography and fiction, independence and incorporation, superhero and crime stories, print and digital formats (for comics), and approval and controversy (from fans, critics, and the general public). With effortless and concurrent references to Milan Kundera’s The Art of the Novel, Sal Buscema’s Captain America, and (his uncle) John Paxton’s Crossfire, he artfully negotiates between the intersections that form the basis for his life as a creator. While some may argue about the originality and genius of the artist, a strict notion of the “new” has generally been jettisoned in the modern age of comics. In its place is the artist who makes great things because that artist can more fully recognize, choose, revise, and reinterpret influences. Ed Brubaker has that ability to negotiate the complexity of the currents that now feed the contemporary comic scene, currents that include not only comics but other media forms as well. For Brubaker, those currents clearly include comics material such as kid-friendly Archie comics and controversial EC crime comics, classic Marvel superhero comics and revisionist superhero comics such as The Dark Knight and Watchmen; comics criticism ranging from that of the infamous Seduction of the Innocent to the ground-breaking The Comics Journal; film sources including the cult classic Harry in Your Pocket and the self-conscious Kiss Kiss Bang Bang; and fiction inspirations in the seminal crime fiction of Dashiel Hammett and the deconstructive crime fiction of Paul Auster. All of this results in sophisticated work in comics (and more recently, in film) that simultaneously lives up to and works beyond expectations. Brubaker is part of a generation encouraging the common reader of comics to expect a more sophisticated narrative and visual experience; working consistently with illustrators that know him well, Brubaker’s work has the potential to retrain the reader to think about comics more broadly in terms of cultural context.

For instance, in Lowlife (1991–1996), Brubaker begins his career with a variation on the autobiographical art comics like American Splendor and Palookaville. Painfully confessional like the work of Harvey Pekar and following the life of a slacker like the emerging fiction subgenre focusing on Generation X, Brubaker refines his artistry and experiments with visual representation to create symbols and narrative unity that extends beyond strict realism. In Sleeper (2003–2005), Brubaker explores the Wildstorm universe, created to nurture independent creativity but for the most part replicating the tropes of mainstream superhero comics. However, when the sleeper of the title, Holden Carver, lives in this grim and gritty superhero world as a double agent, his cover story exposes the arbitrary nature of the superhero standards of good and evil with excessive, metafictive flair. In Daredevil (2006–2009), he furthers the work of Frank Miller and Brian Michael Bendis on the series, informed by hard-boiled detective fiction and film noir. In the process, he makes Daredevil into one of the most tragically depressed characters in contemporary superhero comics: no longer a Raymond Chandler knight in disguise but a Jim Thompson killer whose adherence to conventional virtue is lost in his anger and frustration. And in Criminal (2006–2011), he offers desperate crime stories told by the desperate (and sometimes deranged) criminals. Installments like “Bad Night” and “The Last of the Innocent” implement contrasting comic art styles to represent parts of the fractured consciousness of the protagonists and, quite ambitiously, analyze American comic book history including the supposedly benign influence of Dick Tracy. And with a clear sense of the lost world before the Comics Code, “The Last of the Innocent” rejects the myth of the innocence and juvenility of 1950s culture supposedly represented by the early history of comics like Archie.

With a multilayered approach to his work, Brubaker remains a pulp writer in the sense that he entertains with highly subversive and intelligent work in a medium still somewhat outside the restrictions placed on media clearly identified as high art. With an awareness of how to satisfy a wide audience, Brubaker manages to revise his genres of choice in ways that transform traditional expectations for superhero and crime stories in ways as significant as Robert Mayer’s Superfolks and Haruki Murakami’s The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle. Brubaker demonstrates his self-conscious methodology in his interviews that deserve to be showcased as worthwhile conversations in their own right and as objects of study for readers, scholars, and researchers.

FROM MILD-MANNERED SLACKER TO FULL-FLEDGED CRIMINAL

Ed Brubaker began his career in increments, first as an amateur, then independent, then mainstream comics creator, and he did this at a rather interesting time in comic book history—especially if one is considering the ways that multiple influences on comics seem to be most apparent within the industry. Like many comic book readers of his time, Brubaker became a comic book reader in the 1970s thanks to a box of comics owned by his father that included both Marvel superhero and EC crime comics (Groth and Spurgeon 61). However, his tastes would alter and grow into their maturity as the American comic book industry changed in notable ways in the 1980s and 1990s. After decades of content shaped by the Comics Code and a few major companies, the growth of the direct market and the black and white explosion of the 1980s encouraged comic book creators more than ever before to think beyond the confines of superhero stories written for adolescents. Starting a job in a direct market comic book store in the mid-1980s, Brubaker would be well aware of these changes and the creative thought that they encouraged; already an amateur comic book writer, he read independent black and white comics that defied easy genre classification such as Cerebus and Love and Rockets. And Brubaker was not only aware of the emerging critical culture associated with the direct market via The Comics Journal but he also participated in this mode of thought as a critic as well as a creator. Reflecting on this time period, Brubaker states, “When I was in my twenties, I wrote reviews and articles for a living, while writing and drawing my own comics on the side, because it was just something I had to do” (Hood). As described by comics scholar Bradford W. Wright, it was a time that favored the comic book writer as an artist: “New independent publishers started to target the direct market, and most of these offered creative autonomy” (Wright 262). With discussions of comics as art and creators as rights-holders informing his ideas, Brubaker made overtures into the new independent scene with relatively unsuccessful titles such as Pajama Chronicles (1987) and Purgatory USA (1989), both published by the new, small publisher Slave Labor. Relatively lacking in terms of their mastery of basic narrative and design principles, they nevertheless demonstrate Brubaker’s interest in story content outside the framework of established traditional superhero tropes.

His significant critical breakthrough would come in 1991 with Lowlife, initially published by Slave Labor and then Caliber. It would neatly fit a definition of “alternative comics” developed by comics scholars Randy Duncan and Matthew Smith, who describe them as “usually created by a single cartoonist and present[ing] a very personal vision . . . [with] emphasis on the author more than on characters. . . . due to the radical change in distribution . . . [alternatives were] sold side-by-side with mainstream comics” (Duncan and Smith 66–67). Influenced by a wave of autobiographical comics favored by supporters of the “new comics” like The Comics Journal, Brubaker demonstrates his flair for dialogue and his interest in the dark corners of everyday life. Although not strictly autobiographical, Brubaker drew on elements of his own life and crafted a monologue-heavy approach that recalled the approach of Harvey Pecker’s American Splendor. Due to his future identification as a crime writer, the most consistent reference by comics readers is to the first story in the series, “A Life of Crime,” a series of related vignettes that look at Thomas Booker’s minor criminal acts leading to an armed robbery. Far from being a Crime Does Not Pay making-of-the-criminal story, “A Life of Crime” stresses Tommy’s own ill feelings during a bad acid trip toward the successful crime and amplifies it with a comparison to crimes committed by others. Balancing the thoughts of the character with his first person narrative, we are exposed to Tommy’s desperation: “I held a gun on someone . . . My God . . . I have no soul . . . I was overcome with a feeling of emptiness . . . What was the use of it all? The whole world was just a random series of cruelties” (Brubaker, A Complete 9–10). However, the motivating factor in the story is less the psychology of criminal behavior than the relationships that it endangered and frailty of human connection (something that ultimately became the enduring theme of Lowlife).

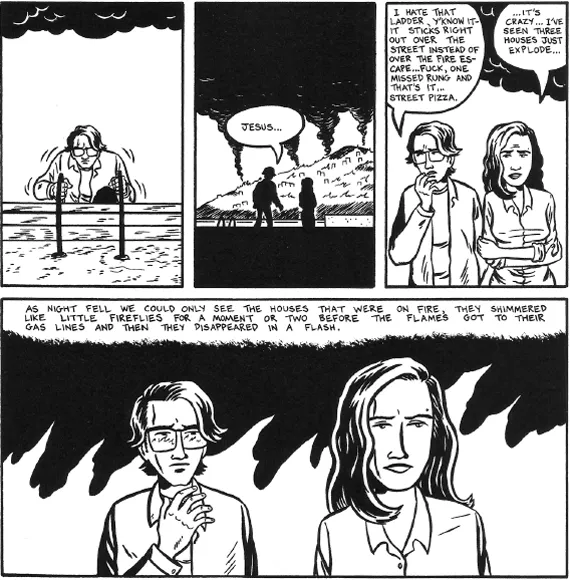

Fig. 1: A massive fire allows Tommy and Sunny to reconnect in a tepid way in the midst of their long breakup in Lowlife #5. (From Lowlife #5 by Ed Brubaker © Ed Brubaker; originally published by Aeon in 1995; available in The Complete Lowlife)

Due to the speculator market that was formed in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Slave Labor often had remarkable sales for a small publisher, but the market that enabled them as publishers of low print run series would come to an end around 1993 when the speculator bubble burst. Without much financial benefit from Lowlife, Brubaker committed to continued work on the series, eventually consisting of five issues, with other publishers over the course of five years. In addition to his commitment to his own creation, he would refine his cartooning style over the course of the series. While he may have recognized the limitations of his own skills as an illustrator (concurrently and subsequently almost always working as a writer), Brubaker shows a greater sense of complexity with his visual presentation; his art becomes shaped by a thicker brushwork style, perspectives of characters are presented in subjective fantasies, and creative angles are used to emphasize the importance of images as counterpoint to monologue. For instance, in “The Girlfriend,” Tommy’s desire for his cheating girlfriend is literally portrayed through a violent sexual encounter but also symbolically portrayed in a more poignant way after she leaves him; with a meager sense of optimism expressed in the second-to-last panel, Tommy decides to clean up his apartment and in last panel, Brubaker offers a wordless presentation of the overgrown and dying garden started outside by his girlfriend. Brubaker acknowledges the continuing autobiographical influence on his work throughout his career but from the start with Lowlife, he argues for the conscious artistic choices that are necessarily part of his retelling of his own story: “I’ve always found it funny that reviewers act as if autobiographical work doesn’t go through any sort of creative process at all, and that the guy who shows himself being cheap all the time, and hitting his girlfriend, thinks he’s showing himself at his finest and it’s just an accident that it got put down on paper” (Brubaker, A Complete i).

At the same time that he worked on Lowlife, Brubaker would collaborate with other artists on short stories for Dark Horse Presents such as “Burning Man” in 1991 and the three-issue arc of “An Accidental Death” in 1992. Like other smaller publishers at that time, Dark Horse allowed creators to own their creations but, unlike many smaller publishers at that time, had a business plan and policies that made it likely to weather the storm from the death of the speculator market (Duncan and Smith 73–74). Quite notably, Dark Horse published several works by Frank Miller, including Sin City, debuting in Dark Horse Presents in 1991, putting Brubaker in the company of a comic book celebrity. Moreover, Dark Horse encouraged not only Miller but also Brubaker and other writers of the time to bring back crime comics traditions in the anthology format associated with the genre in the 1950s. “An Accidental Death” was a major accomplishment, garnering attention for his work from critics and fans alike. Working with Eric Shanower whose illustration realistically represented the tale of urban disillusionment, Brubaker began to develop and refine his longstanding preference for the crime genre—at that time influenced by EC Comics and Jim Thompson novels (but more subtle and humane). In an explicit way, the story continued to use Brubaker’s own life as source material with the main character as a teenager living at the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base (as a boy, Brubaker lived there at Gitmo with his father, a naval intelligence officer). However, as a story of a murder and its cover-up, it also departs more significantly than Lowlife. Although Brubaker would later be frustrated by the amount of words used (especially in first person narration) in his early work (Brubaker, Scene 112), “An Accidental Death” demonstrates an awareness of the importance of images. With wordless panels regularly serving as the frame for the three parts of the story, Brubaker forms a counterpoint to the heavy narration of the story that, for instance, emphasizes the reaction of the main character in fear of recognition in wordless panels.

In terms of the story itself, the narrator, Charlie, and his friend, Frank, are peeping through windows of homes on the base and see a female classmate changing, someone who Frank says he then is dating. Thereafter, Charlie suspects Frank is inventing an elaborate fantasy about his new romantic relationship with her, and one night Frank leads him to the girl’s dead body (another effective use of a wordless panel, large and with an aerial, almost cinematic, perspective). Telling a story of how she fell out of a tree where they were sitting, Frank convinces Charlie to help him hide the body. Eventually, Charlie confesses and Frank is caught and nonfatally shot. In the end, Brubaker returns to the flash-forward frame and, in Charlie’s narration, demonstrates Charlie’s self-protective tendencies and the limitations of an awareness informed by nostalgia: “I guess I hurt a lot of people by going along with Frank but you just don’t expect your best friend to be a psycho . . . sure it happens all over the place now . . . but this was a long time ago and things like that just didn’t happen” (Brubaker, “An Accidental Death, Part Three” 31). Again, with a focus on relationships and the anxiety associated with crime, Brubaker develops a story that sets forth the ease of committing crime, the uncertainty of criminal motive and responsibility, and the gulf between one individual’s perspective and the truth of another’s life. Thanks to this story and others of the same ilk, Brubaker was associated with writers like Brian Azzarello, Brian Michael Bendis, and Greg Rucka, who were hailed as the new crime writers of the new comics scene (Bendis i). As the term comic noir was thrown around, Brubaker would react to the mention of this film tradition in this way: “I don’t know how much any specific film influenced my work, though, it’s more just the themes and the tone of noir that seeps into some of my stuff” (O’Shea). While it may or may not feature hard-boiled detectives and femmes fatale, Brubaker’s work seemed to allude to the existential dread at the root of the subgenre.

With “An Accidental Death” nominated for an Eisner in 1993, Brubaker began to receive other, more sizable offers and soon did work for Vertigo. His earliest work for the adult imprint of DC Comics is an interesting, trippy misfire showcasing the son of Prez Rickard, a teenage president character created by Joe Simon: Prez: Smells Like Teen President (1995); synthesizing some of his early experimentation with the absurd premise of the obscure character, Brubaker develope...