![]()

PART ONE

DEFINITIONS AND HISTORICAL CONTEXT

![]()

CHAPTER 1

“It’s Perfect. It Looks Just Like the Book!”: Scott Pilgrim, Stylistic Remediation, and Transmedia Style

Introduction

On the opening night—August 13, 2010—of Edgar Wright’s film Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, a full crowd attended a screening in one of Los Angeles’s many neighboring cities, Century City. Century City is similar to Culver City or Burbank. It is a city founded on the movies. While Culver City serves as the geographic home base to Sony Pictures Studios (which is located on the former Culver Studios lot), Century City gets its “Century” from studio mogul William Fox. The AMC multiplex located in the Westfield Century City mall is across the street from Fox’s headquarters, and on that Friday night, the theater was packed. The audience roared with laughter at comic writer/artist Bryan Lee O’Malley’s cultural references. They clapped after Wright’s creative staging of the film’s numerous action set pieces. When the lights came up, a female patron seated near me turned to her friend and said “It’s perfect. It looks just like the book.”

While Scott Pilgrim may have been successful earlier that summer at San Diego Comic-Con and the multiplexes located in the posh shopping malls just a few minutes from the beaches of Santa Monica and Malibu, it failed miserably at the box office. Despite garnering complementary reviews from critics and an “A-” CinemaScore from average viewers (CinemaScores are based on a sample of audience members after a screening of a film), the $60 million ($85–90 million before tax breaks) film came in fifth place during its opening weekend. That weekend, Scott Pilgrim earned what industrial analyst Nikki Finke described as being “a pittance”: $10.5 million.1 Eventually, the film grossed $47 million globally, $13 million less than its hefty production budget (ignoring any additional marketing costs).

Like Kick-Ass (2010), another adaptation released that year based on a niche comic book property, the film’s studio—Universal—seemed to have huge expectations for Scott Pilgrim. During that summer’s San Diego Comic-Con, the film was positioned as one of the Con’s main attractions. The outdoor “Scott Pilgrim Experience” took up the courtyard of a neighboring hotel complex and drew massive crowds waiting to get autographs and to collect free merchandise. Moreover, the Con produced lines that sprawled city blocks for “secret” advance screenings. Prior to the film’s release, four of the five top selling titles on Amazon.com were Scott Pilgrim titles and the property was one of the leading “trending” topics on the social networking site Twitter. Despite the Comic-Con hype, social network visibility, and being a movie that looks just like the book, Scott Pilgrim also led to a decline in the formalist trend of stylistic remediation under analysis here.

Yet despite being an economic disaster, Scott Pilgrim is also one of the richest case studies illustrating the process of stylistic remediation at work in the adaptation of a comic book to a film. As the excited theater patron noted, it looks just like the book. But what does this exactly mean? In the following section, I will elaborate on this proclamation by briefly outlining what makes both film and comic books distinct media forms by dissecting their ontological differences. Then, we can begin to look at how Edgar Wright and Universal attempted to compromise those differences via stylistic remediation, a process which eventually—through comics, a film, a soundtrack, and a video game—became a means for a media conglomerate to attempt to unite its transmedia properties. In short, like bullet time in The Matrix before it, the stylistic remediation of Scott Pilgrim became a type of transmedia style.

Adaptation vs. Stylistic Remediation Redux

Filmic adaptation involves the transformation of both the form and content of a previous text from another art form onto film. For decades, these adaptations, when subjected to scholarly textual analysis, were often defined by and against their source texts. As film adaptation scholar Robert Stam has outlined, this theoretical framework of “fidelity criticism” perpetuated a prejudice against adaptations that often resulted in self-defeating paradox. He writes, “A ‘faithful’ film is seen as uncreative, but an ‘unfaithful’ film is a shameful betrayal of the original.… The adapter, it seems, can never win.”2

Yet thanks to the efforts of scholars like Stam, adaptation theory has finally broken free of the intellectual shackles of fidelity criticism. Specifically, Stam—guided by the work of post-structuralists—has encouraged alternative methodologies such as “intertextual dialogism” that “refers to the infinite and open-ended possibilities generated by all the discursive practices of a culture, the entire matrix of communicative utterances within which the artistic text is situated, which reach the text not only through recognizable influences, but also through a subtle process of dissemination.”3 Thus, for Stam, adaptation theory should situate its texts within a cultural context and view them as being engaged in an intertextual dialogue defined by co-presence rather than a hierarchy defined by an original and its copy. As his theory has evolved (Stam originally proposed “intertextual dialogism” in 2000) into the twenty-first century, he has encouraged scholars to view adaptation within the realm of the “post-celluloid world” in which new media theories can play a valuable role in expanding the field and its metaphors.4

Hence my desire to mobilize one of the foundational texts of new media theory—Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin’s Remediation: Understanding New Media—to continue Stam’s move beyond fidelity criticism. Remediation, as examined by Bolter and Grusin, is the representation of one medium in another.5 While adaptations can engage in the process of remediation if, in the words of Bolter and Grusin, the original medium is “appropriated or quoted” in the adaptation, remediations do not rely on a previous text from another art form for material to translate.6 Rather, remediations translate the art form itself. While remediation undoubtedly occurs in adaptations of previous texts (be it Sin City the film or the graphic novelization of Batman), an analysis defined by a focus on adaptations only gives us a piece of the puzzle. This is because remediation is often a broader, dialogical, artistic, socioeconomic process.

As Bolter and Grusin eloquently describe, “Established media, such as film and television, respond by trying to incorporate digital media within their traditional formal and social structures…. What is new about new media comes from the particular ways in which they refashion older media and the ways in which older media refashion themselves to answer the challenges of new media.”7 In this specific case, remediation analyzes the translation of aspects of one medium (film noir lighting) into another medium (film noir lighting as remediated by Frank Miller’s drawings in the Sin City comic), which can ultimately be reacted to by the original form (Frank Miller’s remediations by film noir lighting in the comic as re-remediated by Frank Miller and Robert Rodriguez’s adaptation). My own critical term, stylistic remediation is an elaboration upon Bolter and Grusin’s theory in order to place emphasis on the remediation of formal and stylistic attributes that are specific to one medium or the other.

Definitions aside, now we can turn to defining the formal properties that are being remediated in the film Scott Pilgrim vs. the World. Comics Studies scholar Pascal Lefèvre’s analysis serves as an excellent starting point.8 For Lefèvre, the relationship between the forms of the comic and film can be broadly defined across three formal attributes: sound, iconography, and space. Elaborating upon Lefèvre’s schema, we can also consider the remediation of text (as separate from sound) and temporality. With regard to sound, comics have a textual soundtrack with diegetic sound expressed through word balloons (dialogue) and graphically embellished onomatopoeia (noises).

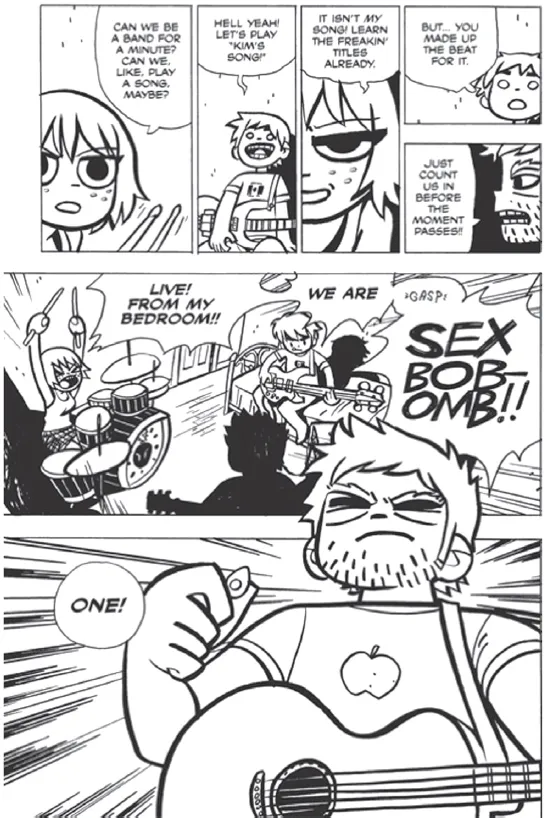

O’Malley’s Scott Pilgrim comics engage in both of the formal norms of representing sound. Word balloons run in abundance (while “silent” comics exist, they are largely a formal outlier) and large, block letter outlined, words like “Kroww” and “Krak” stand in for the sounds of a fist fight. Furthermore, O’Malley’s comic exemplifies a unique formal means of representing the sound of music. Specifically, the title’s hero is the bass player in a band called Sex Bob-omb and the first graphic novel, Scott Pilgrim’s Precious Little Life (2004), showcases the band practicing the song tentatively titled “Launchpad McQuack.” The artist utilizes a remediation of sheet music and textual captions that stand outside the panel to represent the song. Thanks to the inclusion of a chart featuring guitar chords and lyrics, O’Malley informs the reader that “you can play along with Sex Bob-omb at home! It’s easy, because they’re kind of crappy!” Essentially, and this will be elaborated upon shortly, O’Malley’s comic also remediates other media.

While Wright does not go as far to re-remediate O’Malley’s remediation of music, the director continuously underlines diegetic sounds with visual onomatopoeia via the process of aural remediation. For instance, when Wright depicts the band opening “Launchpad McQuack” (before segueing into the credits), he visually represents the drummer’s count into the song and the “Yeah” of the band’s vocalist with words serving as icons. Essentially, despite the change in medium from “silent” comics to “sound” cinema, the adaptation—like the Batman live-action television series that inspired it—stylistically remediates the comic’s representation of sound. As the filmmaker noted in a personal interview, “I really like the style of the artwork and the film is a comedy, not gritty or realistic. I just really wanted to embrace the pop art nature of comics. Maybe because of the Batman television series, which I always liked as a kid but became a dirty word in the 1980s when The Dark Knight Returns came out. But there are things about the ’60s and ’70s books—the colors—that really embraced the pop art and fun that I appreciated.”9 Essentially, this double-layered representational mode encourages the viewer to approach the adaptation as a text that can also be read and watched.

The second formal discrepancy between comics and film in our broad taxonomy is their differing modes of representation. Film is a medium that was—until recently—powered by the motor of photography. Photography, on the other hand, remains a little explored route in American comic art. Drawing—be it through inks, pencils, paint, commercial off-set lithography, or even digital methods—is the primary tool of visual expression. Comic scholar Scott McCloud’s map of the pictorial language of the comic proves useful here. McCloud, who utilizes the form of the pyramid, constructs his map on a two-axis system.10 The horizontal axis, which he dubs “The Representational Edge,” is marked by a spectrum of comic representational methods. For the author, “Reality” (at the far left) and “Meaning” or “Language” (at the far right) defines the spectrum of representation utilized by comics practitioners.11 For instance, photography and photorealist cinema are placed upon the left side of the pyramid while minimalist illustration styles stand at the far right. McCloud complicates his horizontal axis with the vertical axis “The Retinal Edge,” which is crowned by “The Picture Plane.”12 Essentially, as images ascend the pyramid, they become more abstract, which renders them neutral on the “Representational Edge.”

With regard to the pictorial pyramid, O’Malley’s compositions would veer towards the minimalist side of the representational edge and be slightly elevated upon the retinal axis, far from the domain of photorealism. This is because the series—including publication format, narrative arc, and representational mode—owes much to Japanese manga. First, the title was not sold in single, monthly issues that define the majority of American comics. Rather, Scott Pilgrim was packaged in a small digest form by Oni Press and published on a release pattern of roughly one volume a year. The digest form (approximately 7.5 by 5 inches) is strikingly smaller than the usual comic book format (approximately 10.25 by 6.5 inches) and is more familiar to American comic book readers as the typical format that manga is published in. Moreover, the intertwining arcs of Scott’s quests for identity and true love are narrative characteristics of modern shōjo/shoujo (the first is the female variation, the second is the male) manga.

Finally, O’Malley’s character designs (specifically the large, round, eyes of the characters and the minimal use of lines to define emotion) are also in dialogue with the manga aesthetic. For the sake of illustration, here is a page of O’Malley’s Scott Pilgrim placed next to a page of Koge Donbo’s Kamichama Karin (2003–2005, 2007–2008), a popular Japanese manga that also became a television anime (cartoon). In both figures, we notice that both artists have abstracted their characters from the photorealistic by providing few details beyond the mouth and eyes (although Kim Pine, in panel one of Scott Pilgrim, has freckles and Steven Stills, featured prominently in the final panel, has what looks to be the beginnings of a beard). Moreover, the eyes of the characters in both titles are often either large circles (panels 1, 2, and 4 of Scott Pilgrim and the final panel of Kamichama Karin) or “closed” by the use of the line (the final panel of Scott Pilgrim, the first three panels of Kamichama).

Figure 1.1. O’Malley’s Scott Pilgrim.

Perhaps more obvious is that the settings in both titles are minimally established, with the exception of the middle panel of Scott. Moreover, both artists place their characters against white, black, or “subjective” backgrounds that symbolize the emotion of the character (an adrenaline rush in the final panel of Scott, the love and excitement in the first panel of Kamichama). This mode intersects with a difference in the representation of motion between American and Japanese comics that Scott McCloud outlines. Specifically, Japanese comics often engage in a representation...