![]()

All Memories Are Traces of Tears: Wong Kar-wai on Literature and Aesthetics (Part 1 & 2)

Tony Lan Tsu-wei / 2004

From Liberty Times (Taiwan). October 15 (Part I), October 16 (Part II). Interview conducted in Mandarin in 2004. Reprinted by permission of the writer. Translated by Micky Lee from Chinese.

PART 1

Liberty Times editor’s note: An enchanting film is a result of the mix and match of different artistic aspects, a crystallization of the style and the talents of the creator. Today we publish an in-depth interview between film critic Lan Tsu-wei and Hong Kong film director Wong Kar-wai. They begin by talking about his new work 2046. From there they extended to topics such as how Wong’s films make reference to Chinese literature, how they construct a sense of visual space, and what the background of space and time are in the film, as well as the soundtrack. Through the dialogue between the creator and the viewer, the interviewer and the interviewee, Lan and Wong challenged each other’s view of the aesthetics of film texts. The interview revealed the director’s style: rich yet vague, retro-realism yet abstractly imaginative.

Tony Lan: Wong Kar-wai is the premier writer of romantic films. He is also an affectionate commercial seller. His films regularly use the most unique image to sell a star or a city such as Lan Kwai Fong and Tsim Sha Tsui in Chungking Express, the Liaoning Street night market, and Muzha Line in Taipei in Happy Together.1

Wong’s films emphasize mood. He uses a great deal of extremely glorious yet philosophical lover’s discourse to create a yi jing.2 In addition to using oldies, qipao,3 old apartments, and dark alleys to re-create the beauty of 1960s Hong Kong in In the Mood for Love (2000), Wong also adapted from Intersection [Dui Dao] by 1960s Hong Kong writer Liu Yichang.4 In Intersection, Liu wrote about a man and a woman strolling in the streets of Hong Kong, each reflecting on what they see and reacting differently. Liu shows how space and time can be experienced differently and illustrates the desire of worldly men.

A few lines in the essay seem to point out the essence of In the Mood for Love:

Those disappeared times,

Are obscured by a dust-covered glass,

Could be seen, couldn’t be reached.

He has been reminiscing everything of the past.

If he could break through that dust-covered glass,

He would return to those disappeared times.5

Wong says, “Letting the public recognize and know Hong Kong as writers like Liu Yichang have is one of the happiest things to happen to me.”

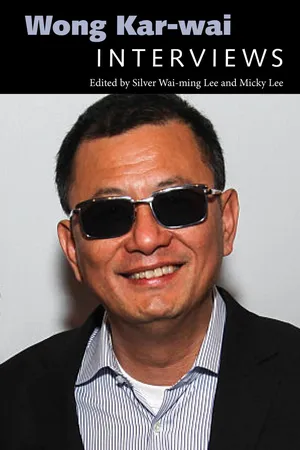

Wong Kar-wai told me that after In the Mood for Love was released four years ago, some people in Hong Kong organized a Liu Yichang symposium to revisit his literature and its historical significance. The essay Intersection was originally only collected in Liu Yichang’s Collection, but it has been reprinted as a book [after the symposium]. “The most incredible thing is that after a French book publisher watched In the Mood for Love, he learned about the writer Liu Yichang. The publisher then translated Liu’s work and published The Work of Liu Yichang in French. This made the old master [Liu] very happy!” exclaimed Wong Kar-wai, whose eyes brightened up behind those dark glasses.

In October 2004, after the release of 2046, the end credits paid homage to Liu Yichang. Those in the know recognized the text on the first screen, “All memories are traces of tears,”6 and some later quotes all come from Liu’s The Alcoholic [Jiu Tu]. Why is Wong obsessive with Liu? What kind of charm do Liu’s writings have to inspire Wong to combine words and images to give birth to new pieces of art?

Recently Wong visited Taiwan, and we began the interview by talking about Liu’s work. We slowly discovered the creative process of this pioneer of romanticism.

TL: In In the Mood for Love, you made reference to Intersection by Liu Yichang and you have publicly paid homage to him. However, in 2046, you clearly made reference to another Liu’s The Alcoholic. You are attempting to start a dialogue with him in your films. Why?

WKW: The Chow Mo-wan character in In the Mood for Love and 2046 comes from Liu Yichang. He came to Hong Kong from Shanghai during the chaos. Despite his past fame, he needed to find a means to make a living. How could he live as a literati? The answer is very simple: he could only make money by writing, so he had to write all genres. He also had to write from dawn to dusk to climb across the boxes.7 Even then, he could barely sustain his living. When I first met him, I saw him work very hard every day. He started to write once he climbed out of bed and continued until eight or nine o’clock in the evening. His greatest joy was to see a movie or take a stroll with his wife every once in a while.

Chow Mo-wan in the film is a 1960s writer. In Liu’s writings one can find a lot of information about the daily lives of writers of that era. In In the Mood for Love, I used his lines in Intersection in an early scene. In 2046, I made reference to The Alcoholic such as using the quote, “All memories are traces of tears,” and others in three screens. The main purpose is to pay homage to intellectuals in 1960s Hong Kong. Reviewing Hong Kong literature of that time, one can tell those writers had to write a lot every day. In order to make a living, they could not write about a grand ideal. They wrote erotica and wuxia genres. They struggled between their conscience and reality every day. All these writings showed they had no choice in how they wanted to live; however, there were some writers who insisted on writing something that they could be proud of in addition to writing pulp fictions that sold well. Liu is one of the representative figures of the latter group.

TL: Why didn’t you directly adapt from Liu’s work when you like it so much? Why did you write an original screenplay?

WKW: I have always wanted to adapt The Alcoholic, but Liu had already sold the rights to another party. Therefore, I cherry-picked a bit of dialogue here and there, hoping to introduce young people to Liu through my films. Then they will read his work.

The writings of Liu are very referential. Reading his work makes one visualize one scene after another; his writings are very imaginative. The writers in that era had a very hard time; they were very low-profile in their daily life. They wrote without complaint. Once they sat down to write, they created millions of words [throughout the years] without realizing it. Recently Liu wanted to re-edit his past work, but I discouraged him from revising those old writings. They were composed under a specific condition of that time. He had not thought of leaving a legacy. Regardless of what the motivation [of writing in that era] was, it is better to let contemporary readers experience how the writers of that era had no choice or dignity. It is most realistic to retain the originality of the work.

TL: Your films are infatuated with the sixties. Is it because you only moved to Hong Kong then, and the new life experience gave you many unforgettable memories?

WKW: Yes, when my family first moved to Hong Kong, we could only rent a room. In In the Mood for Love, the tiny space accommodates people from all parts of the world. It is my own experience to live with a variety of people.

I always remember very clearly that there was a writer living next door. He was drunk every day. One could hardly imagine the boredom experienced by writers. Later I learned that he was a very famous journalist when he was in Shanghai. When he and others moved to Hong Kong, they all felt like refugees. They lived an extremely repressive life because they were caged in a tiny, worn out old room. And they had to write in every genre to make a living since they had no other means of making a living. They had to sell out to make a living. To please the market, they had to write whatever was in demand. Their lives and thoughts were full of boredom and frustration.

TL: In In the Mood for Love, you mastered very well the close relationships between people who live in a tiny space. However, in 2046, you dealt with space in a very different way. The frame was wider, and it greatly enlarged the space: whether it is the sign on the rooftop, the public telephone counter, the corridor of the 2046 train compartments, or the place to exchange secrets. All the characters have been obscured by the wall in front of them and pushed to the corner. This created a much larger space for the film but the feeling of repression increased as well. What was your aesthetic choice here?

WKW: We could use a crowded space to show repressed feeling; we could also use a large space to show a liberal feeling. However, when you use a wide space to contrast with a crowd, you can strongly feel the repressive feeling brought by that space. That tactic highlights people’s feeling of isolation and loneliness. In fact every time I make a film, I want to achieve one thing, which is to imagine what if the protagonists in the film are no longer characters, but space. If we can transform space into a character and to imagine the rooftop on the screen as a character, he then is a witness. He can see what happens on the rooftop. It is like installing a video camera on the rooftop—it can witness and record life.

In 2046, I tried to experiment with a new visual effect. In the past I used a standard lens to achieve a 1.66 (ratio aspect). Space in Hong Kong is very tiny, so the dimension is vertical. The standard aspect ratio is the most suitable to show this feeling. This time I hoped to use CinemaScope on the big screen so the dimension is horizontal.8 All the space on the screen was suddenly enlarged; however, the actual space is as tiny as before. This technique highlights the visual expression, but it poses a challenge to cinematography and sound recording. We [the crew] did not have anywhere to hide, and it was easy to catch us on the camera. Therefore, this time we used a lot of stationary camera shots; we did not move too much.

TL: Your previous stories about love and desire take place in a small room, [but this time] you took everyone to the rooftop in 2046. Going from a closed space to an open one, from the location and the expression of the rooftop, you have shown a new visual world to the audience. What was your conception?

WKW: I have not thought about that carefully; it was a natural reaction. The location was originally a prison where they jailed the political dissidents during the riots in 1960s Hong Kong.9 The location has been preserved until now. When I shot the film, I transformed the prison into an inn.

To me, the rooftop is a very nostalgic place. When I was young, we always went to the rooftop to play. We chatted about this and that there, or we went there for an escapade. But now the space and the concept of the rooftop seem to have all but disappeared.

In In the Mood for Love, Tony Leung (who plays Chow Mo-wan) has a home. All the activities take place inside the home. In 2046, his activities take place in an inn. An inn is a public place. It is hard to find a private space; Therefore, the rooftop is the best arrangement. the rooftop has become their private space.

TL: Speaking of the use of the rooftop space, it reminds me that in every scene on the rooftop, you use Casta Diva of Norma written by the famous Italian opera composer Vincenzo Bellini. From the music in the prelude to the voice of the female soprano, [the image and the music] form an intriguing combination. Film scholars noticed that in this edited segment, you used music to show the characters’ emotions. You have accurately corresponded a make-believe world to the emotions in the drama; this also enriches the imaginative quality of the film. Did you start from the music? Or was the music something you thought of during postproduction?

WKW: The original story of 2046 was not as complicated as the final cut of the film. I wanted to use the number 2046 to tell three stories—each with an opera music theme. They are Norma, Tosca, and Madama Butterfly.

Western opera has to have a recurring theme. At the end of the day, Bellini’s Norma talks about vows and betrayal. This is very close to what we thought of vows at the beginning [of the production]. (TL’s note: Norma is a priestess of Druids, she should represent her people and defend them against Roman invasion, but she falls in love with the Roman Proconsul and bears him a son. She has broken the vow she made with the Druids people. However, the Roman Proconsul falls in love with her assistant, the deputy priestess, and Norma experiences her lover’s betrayal.) During the film development, only Norma remains [out of the three operas]. The reason is that the story of this opera is quite similar to the plot involving Faye Wang. In fact, the music came first, then there was the rooftop. Because we had the rooftop, then we had Faye Wong in it.

I used Casta Diva in Norma because of two simple reasons: the rooftop is like a stage. First, the story of every character in 2046 is like a play on the stage; seco...