![]()

CHAPTER 1

March 1955: Discharged from the Navy

The plane began to slowly descend as it made its final approach to the New Orleans airport. The sun was below the horizon, but the sky above and around us was bright; below, the earth was enveloped in darkness, with sprinkles of lights here and there. As I pressed my head against the window looking forward, I could see the glow of the New Orleans sky.

I was about to resume my civilian life again, but not as it was before—that was impossible. Too much had happened to me during my four years in the navy. I was changed forever; older, wiser, and certainly no longer naïve. As we flew over the Mississippi River, descending more rapidly, the city seemed to be alive, its multitude of lights akin to corpuscles in a body—a giant mother receiving her children. The wheels touched the landing strip, bounced once, then settled down to begin its taxi to the small air terminal. This would be the last day I would wear my navy uniform unless, God forbid, we were forced into war again. I was leaving with the rating of second class petty officer, which is the equivalent to a staff sergeant in the marines or army.

Descending the steps from the plane, I walked towards a fence behind which scores of people waited for family or friends to appear. As I neared the gate, I saw four people waiving to me: Dad, Mom, my brother Donald, and Stella. I was home!

◆ ◆ ◆

Three months later, in June 1955, I sat in a straight back chair in the office of John McCrady, director of the John McCrady Art School. I was there to be interviewed regarding enrollment in the school on a full-time basis. The school taught fine and applied art, my reason for selecting this school.

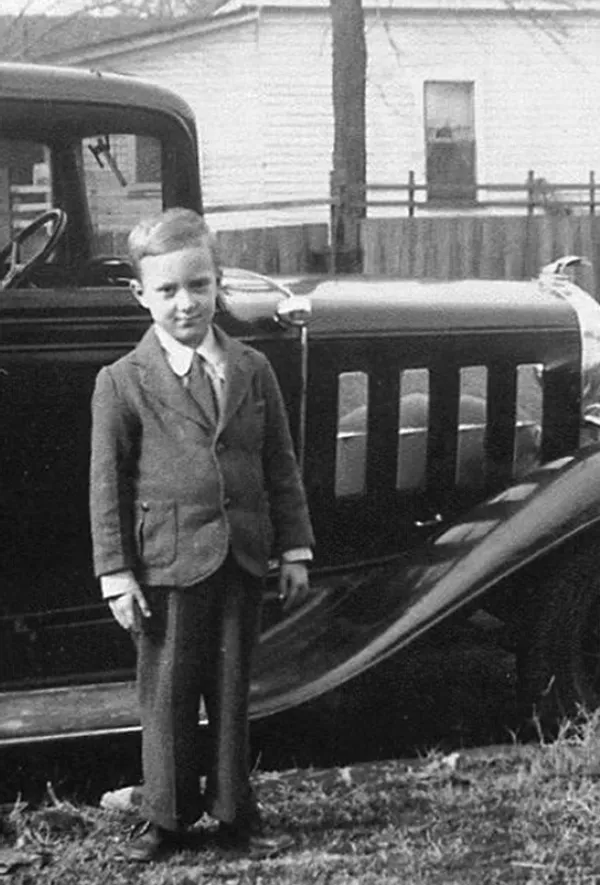

Rolland, age six, by the family car, Grenada, Mississippi, 1937.

“I’ll never be able to do anything this good,” I said to myself as I slowly reviewed the walls. They were covered with very adept drawings of nudes, both male and female. “I must be nuts!” Slowly I rose from my chair, deciding to slip out and forget about art. But just as I stood, Mr. McCrady came in and sat down behind his desk. He was a man probably in his mid to late forties with a receding hair line of dark black hair, a dark black mustache, and deep brown eyes with heavy black eyebrows. Courtesy demanded that I go through with the interview, so I shook his hand and sat back down. It would prove to be yet another in a series of events that directed me to pursue a career in art.

“So, I understand you want to enroll in our little art school.” said Mr. McCrady. He smiled.

“Yes sir.”

“Why?”

I hesitated, and then answered: “I’ve been interested in art for as long as I can remember. I was a sickly child, with asthma and severe anemia, so I spent a lot of time at home, missing school, and frankly, I enjoyed nothing more than drawing and painting what fascinated me. My dad was very talented in art and I believe he passed some of that on to me. I’d watch him paint, then get my pencils and paper, and draw.”

Mr. McCrady leaned back in his chair, saying: “And you kept this interest up through high school?”

“Yes, as well as one semester in college, until I joined the navy. It was four years without art, but now that I’ve finished my duty, I still want to give art a serious try.”

“Good. We’ll certainly do all we can to teach you the basics and beyond; getting you on the right track.”

After our conversation, he gave me a tour of his school, walking me into the large room next to his office. Several students were assiduously working on paintings or charcoal drawings of still-life arrangements. On the side of the painting storage space was a quick sketch by Thomas Hart Benton, who had been a good friend of McCrady’s.

The McCrady Art School was located at 910 Bourbon Street in the French Quarter, ensconced in a building erected in the 1830s or 1840s. The structure was owned by the mother of his wife, Mary Basso McCrady, and was full of the charm that only an old building could offer.

Mr. McCrady was a kind man with glistening, intelligent eyes. A great painter of the regionalism school, he was equally gifted as a teacher, perhaps more so. He turned out to be the perfect instructor for my talent, such as it was. The aspects of art he emphasized were those for which I seemed to have the most talent: drawing, composition, and perspective. It was fortunate indeed for me that he returned before I left his office; what would I have become if he hadn’t?

After we finished our tour, Mr. McCrady instructed me to go downstairs where watercolor and commercial art were taught by his wife. I wasn’t interested in commercial art, but it seemed a good idea to put it into my curriculum. Mrs. McCrady’s brother was Hamilton Basso, author of the highly acclaimed 1950s novel, The View from Pompey’s Head. She was quite talented in her own right, especially in watercolor and commercial art. A petite lady with salt and pepper hair pulled into a bun, she appeared to be a very vibrant person. But most notable to me was, as I would learn over the years, her complete devotion to and support of her husband and his career; their art school; and their much-loved daughter, Tucker.

Shortly after being discharged, I had bought a second-hand Dodge. Although it used up much of my discharge money, the car was worth every cent. As I drove the Dodge home after the McCrady interview, I was relieved that it was over. I had enrolled as a full-time student; I had much to learn. Especially after seeing the skillful drawings in Mr. McCrady’s office, I was unsure of how good I was or could become—and drawing was my strong point! As for painting, I had practically no experience with it. However, I thought, “Well, that’s why I’m going to school.”

Before the interview, I had called the Department of Veterans Affairs inquiring if there was an art school in New Orleans that accepted veterans on the G.I. Bill of Rights, established after World War II. There was only one, The John McCrady School of Fine and Applied Art on Bourbon Street in the French Quarter. I would receive $110 each month in veterans’ benefits, which would pay my tuition of forty dollars a month, with some left over for supplies and so on. It wasn’t much, but I had a car, some savings, and I could get by while living with my parents.

The general public has a romantic concept of artists living in sleazy third-floor apartments, drinking wine while painting beautiful, nude girls, then sleeping with them after the posing was over. There probably are some artists who live this lifestyle, but in truth, art is indeed hard work, and very few who pursue it as a career are able to continue throughout their lives. Even those able to follow art as a career for their entire lives have a hard time keeping enough money in the bank to pay the bills.

The drive from the interview back home passed swiftly as my mind wandered far afield. I had thought long and hard about this decision. As I turned onto Elysian Fields, a wide thoroughfare that runs from the Mississippi River to Lake Pontchartrain, I said out loud, “Quit all this negative conjecturing, Golden. Just begin! Who knows—you might actually be good enough to make it. You’re sure hardheaded enough!”

I pulled into the driveway and parked behind dad. The scent of mother’s roast came wafting through the side door.

“I’m going to make it,” I said again.

At last I had made a decision; it would be art. Not knowing what I wanted was actually harder than making the decision.

![]()

CHAPTER 2

Art School

Dan Banister, my good friend since high school days, had been discharged from the navy just two weeks after me, and we caught up on this lost time in the navy while I was waiting for art school to begin. Much of our entertainment involved going to the Eight Suns Bar on Franklin Avenue and having a few drinks. Dan could drink more than anybody I’d ever seen and not show it—well, at least not until he went beyond his sober limit. I didn’t try to keep up with him because too much liquor made me sick, and I did not like praying to the porcelain God on the floor afterward.

Dan and I were about as close as two men could be; we were practically brothers. We had been close friends for years and there wasn’t anything we couldn’t discuss or wouldn’t do for each other. At one point after his discharge, he even lived for a time with my parents, my brother, and I in our two-bedroom house on Selma while he got on his feet.

Once school began in September 1955, I was ready and found the pace easy. Mr. McCrady, or Mr. Mac, as we affectionately called him, made it that way with his patience and subtle prodding; this was welcome to me after the frequent, stressful tasks demanded in the navy. The level of intensity was determined by every student within themselves; the degree to which one desired to improve determined how much pressure they put on themselves. The more pressure, the greater the stress.

I must not forget the sequence of events that helped guide me to becoming an artist. Stella was a devout Catholic, and when I was home on leave from the navy we usually went to Mass together, even though I was still unattached to any denomination. At one particular Mass, the priest gave a very thoughtful sermon; he said God gave each of us a talent, some more than others, and it was a sin not to use it. This struck home with me while I was still trying to determine what I was going to do with my life once I left the navy. I had traveled thousands of miles and even endured a few dangerous times without ever being injured. I strongly believed that therefore I needed to take advantage of both of these gifts, which were my artistic talents and my life being spared during the war.

John McCrady teaching students at his art school (Rolland is sixth from left), Bourbon Street, 1955.

Now, three or four weeks into school, I had worked my way through three still-life drawings in charcoal that Mr. McCrady made every student do before beginning to paint. His school was in many ways like the old Bauhaus schools of Germany and elsewhere in Europe—emphasizing the basics of art, drawing, composition, perspective, values, and understanding colors and their effect upon one another. Some students felt this stifled creativity, especially if they had had any previous instruction.

Mr. McCrady would say, “How can you create art if you don’t understand its basic principles?” This failed to pacify some, but it worked well with my mindset. He also said, “Creativity, if you have it, because not everyone does, will come and be built upon a sound foundation.”

Those who disagreed left; those who didn’t care either way stayed—along with those like me who agreed with him. In the end, his school produced many fine artists.

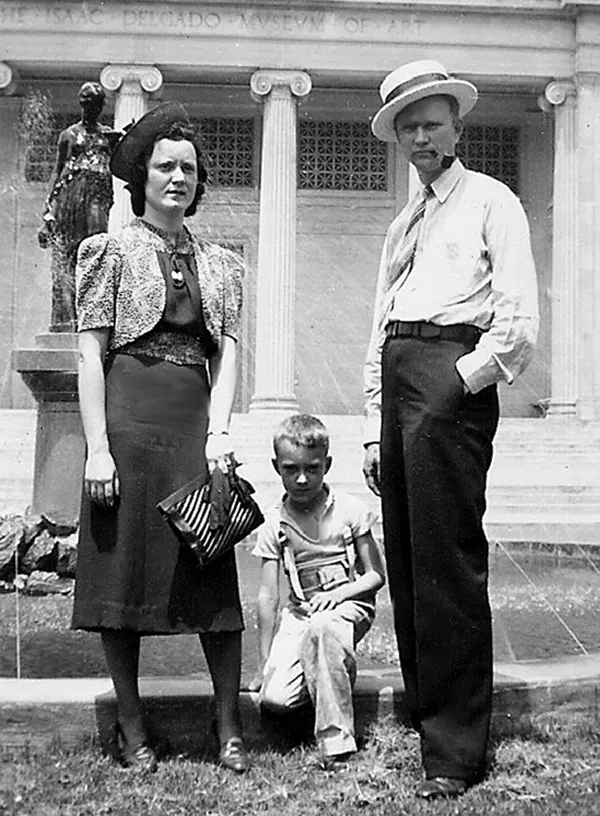

Rolland with his parents in front of the Delgado Museum, age seven, 1938.

After completing the charcoal drawings, we were instructed to begin our first oil painting. The medium was totally foreign to me, and I struggled with it until the end, managing to get the paint all over myself and my clothes in the process, something I continue to do to this day. However, I felt I’d done a pretty good job, considering my lack of knowledge of the medium, and left school for the weekend buoyed by my effort.

The next day was Saturday, and not having anything else of importance to do, I decided it would be a good day to go to the museum in City Park. “I’ll be back later,” I yelled to Mom as I went out to my car.

The museum, called the Isaac Delgado Museum of Art after its benefactor, was located in a lovely building constructed in an old European architectural style. It sat in the middle of a circle surrounded by a roadway leading in and out of the park. Upon entering the museum, the visitor is engulfed in a large, vaulted ceiling foyer, or entrance gallery. I remember coming here as a child with mom and dad, awed by the paintings and the space. Dad spent time trying to teach me about different styles, including impressionism, and how one had to get back from the painting to really see what the artist was attempting to convey.

Now I’d look upon these works with greater appreciation and knowledge, and herein lay my shocked reaction: Oh my God! My work—my one completed painting—looked like something scratched out by a four-year-old child! I sat on one of the benches in the grand foyer to regain my composure and my senses. At last I calmed down and resumed viewing the paintings, reminding myself I had only one painting under my belt.

I’d never been too cocky about my abilities, despite usually being one of the best artists in class growing up, but I was confident, perhaps falsely so. This was a lesson in humility that I evidently needed. I vowed to return to the museum often. Outside, I went down the steps leading to the museum’s entrance, saw a bench near the pond, and decided to sit and think while all was fresh in my mind. A flock of ducks swam around under the shade of a tree as I pondered what I’d just experienced. It had been a bitter pill to swallow, but a good thing, in reality. How could I have been so absurdly insolent to believe I was better than I was? My God, I didn’t even know how to mix a decent gray!

◆ ◆ ◆

I followed Mr. McCrady’s instructions, assiduously seeking answers to the many art problems that burned in my brain. Do lighter objects come forward or recede? Do images in the distance all become grayer or do certain colors still prevail over long distances? Can sunlight be a spotlight on certain images, or does it bathe everything equally? Values can transpose even the most colorful scene into black, gray, and white, but red becomes black without color and the value of yellow seems too light—yet Mr. McCrady insisted we learn the relationship of values to color; puzzling.

Despite all of these questions, art school seemed to be going well as far as I could tell. Each Friday was critique day, when the “master” himself analyzed everyone’s current work in front of all the students. By listening to his criticism of others’ work, as well as your own, you were able to gain a wealth of valuable information.

Not only did Mr. McCrady stress learning values, he was a stickler about drawing and composition. If you came away with anything, it was probably one or both of these two facets of crea...