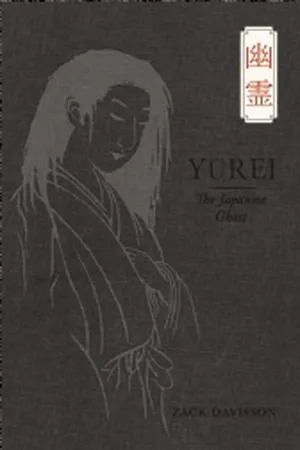

![]()

Chapter 1

THE GHOST OF OYUKI

幽霊図: (お雪の幻)

Otsu, Ōmi, Japan. The 2nd year of Kan’en, in the reign of the Emperor Momozono-tennō. A hot, damp summer’s night …

Maruyama Ōkyo opened his eyes from a fitful sleep and beheld a dead woman. She was young. Beautiful. And pale. Unnaturally drained of color, her bloodless skin peeked from her loose, bone-white burial kimono. Her bleached appearance was contrasted only by the thin slits of her black eyes and by the long, black hair that hung disheveled across her shoulders. She had no feet.

But her face was calm. Soothing. There was nothing in her eyes to make the seventeen-year-old Ōkyo apprehensive. The dead woman watched him a moment — and disappeared.

An artist by training and nature, Ōkyo sprang from his futon, grabbed his brushes and a nearby roll of silk and mustered all of his skill to capture the apparition exactly as she had appeared before him. His lover, Oyuki.

The Ghost of Oyuki 2 was painted sometime in the year 1750, on the morning directly following Maruyama Ōkyo’s strange visitation. According to a note on the scroll box put there by a former owner named Shimizu, the painting is an image of Ōkyo’s mistress, Oyuki. She was a geisha at the Tominaga geisha house in Otsu city in the province of Ōmi, modern-day Shiga prefecture. Oyuki had died young; how or when the note does not say. Ōkyo mourned her deeply. Perhaps too deeply.

This young lover, Maruyama Ōkyo, was no ordinary artist. Born Maruyama Masataka into the farming caste in Ano-o (modern day Kameoka city, Kyoto prefecture), while still a young teenager, Ōkyo moved to Kyoto city and began his artistic career at a toyshop painting the faces on wooden dolls. From there he sharpened his skills, apprenticed to various master artists both indigenous and foreign.

By the time Ōkyo came into his own, he was a man of incredible talent and reputation. Founder of the Maruyama school of painting, Ōkyo regularly produced commissioned paintings for both emperors and shōguns as well as created major works for religious sites. His monumental 148-foot scroll, The Seven Misfortunes and Seven Fortunes (1768), hung in Enman’in Temple, in the same town of Otsu where Oyuki had died.

Ōkyo was the ultimate naturalist painter and emphasized direct observation of subjects — if he painted something, you could trust that he had seen it. Perhaps he would make some flourishes of design and artistry, but he fabricated nothing from whole cloth. Ōkyo even insisted on using living models when depicting horrifying scenes such as a man being ripped in half by two bulls for The Seven Misfortunes and Seven Fortunes. In pursuit of the real, he did not shy away from forbidden subjects. Ōkyo was the first Japanese artist known to use nude models for life drawings, considered pornographic at the time.

In fact, legend spread that the owners of an Ōkyo original must be careful. The paintings were so realistic, so true to life, that the subjects took life from time to time and strolled off from their respective surfaces.3

Ōkyo’s insistence on observation was more than just an artistic sentiment. A devout Buddhist, Ōkyo’s introduction to The Seven Misfortunes and Seven Fortunes stated that man must find Buddha in the here and now, in the real world — not in fantastic visions of other realities. Reality was his religion. But what he was seeing that hot, damp summer night tested his devotion.

Perhaps his emotions for his lost love were strong enough that Oyuki’s spirit was bound to the Earth. Or perhaps it was nothing more than the desperate longing of a lonely young man seeing what he so very much wanted to see. Whatever the reason, one night Oyuki appeared to Ōkyo, hovering over his futon and watching him contentedly. Not a terrifying vision, not something to wake him shuddering in his bed, Oyuki was merely there, watching, peacefully.

When he woke that morning, the image in his mind was painfully clear. He knew immediately what he must do. Grabbing his brushes and a nearby roll of silk, using all of his considerable skill, Ōkyo carefully painted the portrait of his lover. He captured her exactly as she had appeared to him in the night. Perhaps, he may have thought, it was what she wanted: To be painted. To be remembered. To be immortalized.

When he was finished, he had created more than a simple picture. Unknowingly, he had painted the first yūrei-e, meaning a portrait of a ghost, a yūrei. He had given Japan a true image of what their departed looked like. And this painting of Oyuki would become more famous and outlast anything else Ōkyo ever painted — lasting longer than his commissioned works for emperors and shōguns, becoming more famous than his 148-foot scroll that hung in the town where Oyuki had died.

In the age of cameras and digital imagery, of stunning makeup and special effects so life-like it can be difficult to tell fantasy from reality, The Ghost of Oyuki is not such a startling image. Light colors on a creamy silk; it is a mere wisp of a picture. Oyuki’s figure takes up only about two-thirds of the roll of silk. Soft lines curve gently, creating the outline of a woman. Ōkyo gave his muse a Mona Lisa-like inscrutable half-smile under hard eyes, an expression that either reprimands or romances depending on the angle. The dense black of her hair fades to nothing more than flicks of a brush by the time your eye makes it to the bottom of her kimono. Her right hand, tucked into the folds of her kimono, covers her breast. The diaphanous kimono fades to nothing below her waist. She has no feet.

It is hard to see that this is the literary great-grandmother of famous Edo period ghosts such as Oiwa, Otsuyu, and Okiku, known collectively as the San O-Yūrei (三大幽霊), or Three Great Yūrei of Japan. Or of modern horror movie specters like Sadako and Kayako. It is hard to see that Oyuki’s legacy would send millions dashing for the light switch after getting a good scare in the company of friends.

Maruyama Ōkyo would paint other yūrei-e during his lifetime. These were usually commissioned paintings, sometimes portraits of family members that had passed on or simply collectors who wanted their own ghost painting by the famous artist. He still used models for these portraits, usually a living family member who resembled the dead person.

Ōkyo did not give up attempting to capture another authentic yūrei. In his 1894 book Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan, Japanologist Lafcadio Hearn tells a story of Ōkyo being commanded by the shōgun to produce an image of a yūrei. In response, Ōkyo went to the house of a sick aunt and waited by her bedside for her to die so he could paint her escaping yūrei as it left her body. He was not able to capture the evacuating spirit, but had to content himself with sketching her emaciated body as she had the look of one long dead. But none of these paintings had the same impact.

So what makes The Ghost of Oyuki unique? How could this single, simple painting so dramatically influence a culture?

Part of its fame is the story. A dead lover returned from the grave. A passionate young artist who immortalized her. Sex and death, with a tangible souvenir of the encounter. All of the necessary elements are there to create a legend. But there are many paintings with interesting stories, and the impact of The Ghost of Oyuki is due just as much to the fame of the painter as to the painting. After all, this was Maruyama Ōkyo.

If Ōkyo claimed this was an actual and honest portrait of a yūrei — not a fantastic image spawned from an over-active imagination — then Japan would believe him. This is what they looked like.

And credit where credit is due — as we will see, Ōkyo’s timing was perfect. The Edo period had been waiting for him.

![]()

Chapter 2

WEIRD TALES

怪談

“ … Shogakan Gahakudo was a legendary gathering place for hyakumonogatari kaidankai. At the entrance hung a permanently burning lantern, of the sort normally only used for the Obon festival of the dead. You didn’t even need to plan the event — such was the passion for the game that on any given night you could be assured a spontaneous round of storytelling would begin, with members alternating turns, exchanging their favorite kaidan.”

– Translated and excerpted from Nihon no Yūrei,

1959, Ikeda Yasaburo

When Maruyama Ōkyo roused from sleep that morning in 1750, he awoke in the unprecedented era of peace and refinement of Edo period Japan (1603-1868). Japan was busy transforming itself into the country we all know today, and many of the things Japanese — the aristocratic samurai and the artisanal geisha; the elegant theater of bunraku and the wild spectacle of kabuki; the floating world of ukiyo-e artists — sprouted and flowered during the Edo period. Threaded throughout each of these were ghost stories, kaidan. And yūrei.

The Edo period was a renaissance of the weird. Noriko Reider says in her book Japanese Demon Lore that the Edo period was “an interesting time and space in Japanese culture in which individuals from all walks of life, on some level or other, seem to unite in their belief in the supernatural.” The touch of the supernatural was in everything in the Edo period. And the touch of the Edo period is in all of Japan’s supernatural folklore. They are intimately intertwined.

What was so special about the Edo period that made it ripe for the otherworldly? A number of different elements came together to create the perfect storm that was the Edo period kaidan boom — to begin with, the closure of Japan’s long history of civil wars.

Japan must have heaved a collective sigh of relief when almost 150 years of fighting finally came to an end. Proceeding the Edo period was the Sengoku, or Warring States, period. From the start of the Ōnin War (1467–1477) to the final defeat of the Toyotomi clans by Tokugawa Ieyasu at the Siege of Osaka (1614–1615), Japan had endured almost constant warfare.

Periods of war do not easily breed kaidan. People do not want to read or be entertained by gruesome tales of blood and vengeance when there is the very real chance that they might have their head chopped off or be skewered on a spear just for the crime of being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Or find themselves in the sights of a hungry and desperate soldier on the run.

With the peace of the Edo period, people finally felt safe enough again to seek amusement in the supernatural, to play with the grave that they no longer felt themselves a hair’s breadth from occupying. The ghosts of Japan were only waiting in the dark for their chance to rise again. The foundations had been laid long ago.4 To know the full story, we must delve into Japan’s literary past.

Japan’s gods and monsters were born in the Kojiki (Record of Ancient Matters). The oldest known work of Japanese literature, the Kojiki dates to the eighth century, most likely 712. Claiming to be a historical record of Japan, in truth it concerns itself with creation myths and the hijinks of gods — like Izanagi and his sister-wife Izanami, the proto-yūrei about whom we will learn more later.

The Kojiki was a commissioned work by the ruling family meant to authenticate the divine lineage of the emperor and cement the Yamato clan’s right to rule. Rumors persist of older books, such as the Kujiki (Record of Former Matters), which claims a publication date of 626, or the Tennōki (Record of the Emperor) and Kokki (National Record), both of which claim publication dates of 620. However, no authentic copies are known to have survived. These books are largely considered either forgeries or apocryphal.

Not that the common people cared. While the emperor and the ruling family fretted over their bloodlines and magical ancestors, the rest of Japan did what people do everywhere — gathered round the fire to swap myths, legends, yūrei tales, and occasionally a few true stories thrown in for good measure. Scholars started writing down this oral folklore around the Heian period (794–1185), when Buddhist monks created the genre called setsuwa.5

The monk Kyōkai wrote the first setsuwa, called the Nihon Ryōiki (Japanese Chronicle of Miracles), sometime between 787 and 824. Kyōkai was a self-ordained monk; a wanderer with no order or temple. According to his own admission, he was not particularly learned in the esoterics of his faith. But he was passionate and devoted to sharing the lessons of Japan’s latest religion, Buddhism.

To give you some idea of its contents, the Nihon Ryōiki is occasionally known by its full title of Nihonkoku Genpō Zen’aku Ryōiki (Miraculous Stories of the Reward of Good and Evil from the Country of Japan). Kyōkai intended the Nihon Ryōiki to be a teaching tool about the laws of karmic causality. He gathered local legends and supernatural stories, and coupled them with didactic Buddhist teachings.

The stories had titles like Of an Evil Daughter Who Lacked Filial Respect for Her Mother and Got the Immediate Penalty of a Violent Death or Of a Monk Who Observed the Precepts, Was Pure in his Activities and Won an Immediate Miraculous Reward. Simple and direct, the tales in the Nihon Ryōiki had uncomplicated plots that showed how good deeds are rewarded and evil acts punished in this lifetime. No one ever accused Kyōkai of subtlety.

Like the Nihon Ryōiki, the majority of setsuwa were written with an educational motive in mind. Arduously...