- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Trans women—assigned male at birth and later transitioned into a female gender— are recently in media because of celebrities and controversial legislation. Therefore cis men—who identify with a masculine gender they were assigned at birth—are now called upon to share their experiences as lovers of trans women. Using theory and personal anecdotes, the author questions the codes that cis men and trans women use to interpret their own and others' gendered bodies.

Joseph McClellan has taught philosophy, Buddhism, and gender studies, and translated and introduced contemporary French philosopher Michel Onfray's A Hedonist Manifesto: The Power to Exist.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

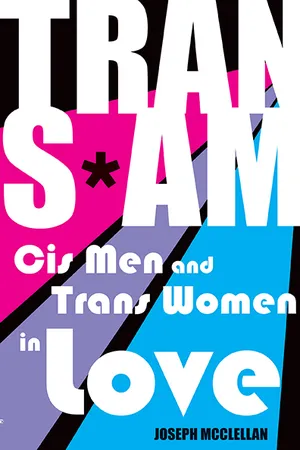

Yes, you can access Trans*Am by Joseph McClellan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Gender Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

NAVIGATING THE SEAS OF IDENTITY

CAN WE DEFINE THE TRANSAM?

Based on conversations with friends and acquaintances, and reading online discussions, published essays and memoirs,1 I believe a large number of trans women resent and continue to reject any effort to validate cis—especially, but not exclusively, male—attraction.2 They may be distrustful of, even disgusted by a cis person, perhaps especially a cis man, who would expressly consider trans identity to be an attribute of special attraction—that is, who could self-identify as transamorous. They assume that to name this affinity is objectifying and Othering. Some friends advise me that the term transamorous once again trans people, especially women, into the object of a fetish; it’s just another, anodyne name for the rightly despised “chaser.”3 To identify with trans-oriented attraction therefore seems misguided and irresponsible at best, reprehensible and dangerous at worst. This seems to me to lead us to an impasse. If the transamorous person is constrained from naming their love, their individuality is denied and they are compelled to dissimulate or sublimate their attraction. The trans lover suffers from this arrangement too; their “transness” is tagged with an unnecessary metaphysical heaviness that also must be dissimulated or sublimated. In place of the common pejorative term “chaser,” a welcoming but accurate term can help resolve this conundrum.

Due to actual and historical relations of power, the cis man’s attraction to a trans woman is arguably the more problematic situation, whereas the cis woman’s attraction to a trans man is complicated in other, less obvious ways.4 And for some (not all) trans women, it may seem that in order to mirror (or complete?) her identity, her ideal partner would be a straight man. To be fair, after eons of investment in their dominating identities, cis men have fully earned the distrust of their intentions with trans women. Cis men have largely devised and profited from the gendered economy of external validation in which the “Real Man” is the referential gold standard that sets terms for the “Real Woman,” and so many other fabricated metaphysical terms to label those who are Other, or less, than the “Really Real” (White) Man. While raking in the rewards of this economy, cis men are expected to be consistent, at least, and repose in our unassailable Manhood—a simple truth about reality—and imagine anything Other to be something with a significance relative only to their own.

More often than not, however, I think the objections to the transamorous identity of a cis man are based on an idealization. If we pronounce “Woman” and “Man” with enough conviction, through sheer power of will we can homogenize the differences between us; there will be no need to identify as trans at all. Even “male” and “female” could become two sides of a single coin (in “holy matrimony”), and all individuality and diversity can be dissolved once and for all. I lack confidence in metaphysical assumptions that fuel this faith, and I believe most of the terms that would sustain an abstract discourse about Man and Woman are, and could only ever be, borrowed from the cis-het patriarchy, an oppressive global superstructure in which cisgendered, heterosexual men hold a disproportionate access to power.

Condemning cis men who wish to articulate a distinct sexual attraction to trans women seems to avoid, deny, or suppress a real phenomenon that is not, to my mind, invalid—however problematic it may truly be in our present context. There are, and will continue to be, people who consider “trans” identity to be an attractor in a sexual partner.5 My own attraction to trans women has been evident to me for nearly twenty years and has remained largely unchanged after withstanding much critical scrutiny. I will not be ashamed of my desires, and I am not convinced they are a species of pathology. Moreover, putting my own defensiveness aside, the hasty conflation of any transamorous man with the disapproved “chaser” could have the effect of shaming and silencing transamorous people whose affinity is even far less pronounced than my own.

Take, for example, the hypothetically ideal straight cis male partner for a trans woman. He did not know his partner was trans at first, or maybe had never dated a trans woman before, so her trans identity played no role in his attraction to her. They have a rich and loving relationship for some months or years, and then the relationship fails for some common, predictable reason. This man now has a bank of memories about his former partner. He may recall how one of the things that made him fall for her in the early stages of the relationship was that he found her trans biography interesting and admired her for her life experiences; he found it enriching, under her influence, to learn more about his social environment. It became important for him to interrogate his cis privilege; he clicked with her friends and had eagerly taken part in some trans activism with them. He may also recall intimate moments, her body and the ways they made love, which presented him with a new understanding of his own gender and sexuality.

Now, of course, all of this experience occurred because she is a woman, full stop. However, according to the prevailing discourse, once the relationship with this particular woman who is trans comes to an end, the man must exorcise all of those positive associations that had to do with his former partner’s transgender or sexual identity. If he now seeks another trans partner as a way of again touching upon those fond feelings, he has slipped into pathological fetishization.6 The only thing that could both satisfy this new affinity in him and save him from accusations of being a fetishist would be if he happened again to stumble upon a trans woman unawares. The likelihood of this accidental occurrence recurring after he has already been involved with a trans woman, her friends, and her community is, however, somewhere between low and nil.

In a magnificent PhD dissertation7 and follow up essay,8 Avery Tompkins analyzes this conundrum among the cis female partners of trans men. Their dilemma is not entirely different from that of straight cis transamorous men. Reflecting on her subjects’ video testimonials about their relationships, Tompkins writes:

In her vlog, Beth notes that a failure of available terms to describe her attractions positively means that if she tells someone she is attracted primarily to trans guys, she is labeled a “tranny chaser.” Lacking language to adequately describe her attractions and sexuality, and knowing the danger around speaking these attractions at all, has led Beth to simply not identify with any sexual identity label. So, while there is certainly a potential impact on the trans partner in a relationship who may not have their trans identity affirmed, the cis partner in that relationship is also unable to discuss their own sexual identity in relation to “trans” (Tompkins, 2014: 772).

And relating to my previous consideration of our hypothetical male’s erotic memories of his trans partner, Tompkins observes that their9 subjects “seem to be engaging in a careful and explicit denial of the erotics of transness in order to resist classification as a ‘tranny chaser’” (773). Tompkins contends “that the silencing of ‘trans’ as desirable or erotic does not align with a sex-positive politics” (774) inasmuch as their subjects “were specifically denying any kind of attraction to the trans-specificity of their partners, preferring to say something akin to: “I just like him for him” instead of reveling in (or even bragging about) the erotics of their partner’s transness as some have begun to do in other contexts.”

My experiences suggest there is a common imperative to deny an attraction to certain trans qualities, whether history or physiology, of a trans partner. There are quite a few published discussions of the “tranny chaser” phenomenon, which express different attitudes about the possibility of a non-pernicious trans affinity.

Christin Milloy has put the matter in all fairness:

When a cis person is attracted to a trans person, that should never be viewed (in and of itself) as a fetish, because that would cast any relationships between trans and cis people as shameful . . . But what about when cis people specifically seek out sex with trans bodies, in a way that serially objectifies us, and disrespectfully treats us as their kink? . . . While their attraction for trans people mustn’t be stigmatized, their bad behavior toward trans people absolutely should be. . . .10

As someone who accepts his position in the crosshairs of such a critique, I find nothing at all to object to there.

From another angle, Charley Reid focuses on what she perceives as a tendency for transamorous men to reduce a trans woman to her physical features, taking no interest in her character or biography. Reid writes:

As trans women, how are we supposed to be with someone who has stated that their reason for being attracted to us has nothing to do with our personality or our tastes or our perspective on life, but with our particular configuration of body parts? Moreover, how are we supposed to feel when our culture assumes this kind of sexualization is the only way for us to be wanted?11

When I read this passage from my own perspective as a self-identified transamorous man, it horrifies me to know there would be people who know and say they are attracted only to the physical features of a trans woman. I emphasize “only” because, as Tompkins suggests, we can distinguish between those who see trans identity as one characteristic among many others, and those who might consider trans identity to mean only a physical attribute. It is upsetting for me to hear that some men do confuse genuine mutual attraction with a passing interest in bodies.12 I agree such men are not recognizing trans women, but it does not lead me to conclude that no man can ever have a sexual or romantic preference for trans women, among other preferences.

Undoubtedly, as Reid’s point appropriately implies, the history of exploitation and dehumanization of trans women in particular makes the ethics of transamory particularly problematic. The particularities of the identity “trans woman” merit the extensive consideration I give in these chapters because a self-identified transamorous man presupposes her particular identity. Having a fetish can be an issue between sexual partners, but I assume, in principle, society can tolerate all kinds of diverse sexual activities between consenting adults and not explode. To be sure, transamory is particularly problematic for historical reasons. Yet there are plenty of cases where a person is desired for their height, their breasts or penis size, their accent, or any number of attributes marked as uncommon or fetishistic objectifications, and exploitation or dehumanization does not necessarily follow as a consequence. My point here is not to establish an equivalency between these or any objects of fetishization (for, there are some that most certainly push boundaries of what constitutes consent or harm), but to draw the most relevant ethical distinction. The distinction, I believe, assumes the ethical weight is not derived from the objectified body (its configuration, for example), but from the objectifying behavior and its ethical implications. When any of these forms of making a fetish of a feature becomes a pattern, when the person with this “preference” seems to privilege this one attribute over many other considerations of the person’s full range of features, they open themselves up to ethical criticism.13 The reduction of an infinite subjectivity’s fullness to a finite object’s narrowly delineated feature(s) merits ethical criticism. The objective attributes—which arguably do not define the subject—are, it would seem to me, neutral per se to ethical judgment; that is, an objective attribute, even more specifically a physical feature (like configuration), is objectified in some contexts differently than in others, under some conditions but not others. The problem is not this or that attribute as such, be it trans feminine or something else. The problem is that we face essentialism or objectification as an act, and though I certainly acknowledge that trans women are particularly vulnerable to this reduction for unfortunate—and hopefully rectifiable—historical and cultural reasons, nonetheless I contend there is no moral or ontological reason to distrust trans attracted identities any more than lovers of skin ink or large feet.

I do not consider myself a serial dater, so often a year or two has passed before I have felt a strong enough connection with someone to date them seriously. In the interim, the preponderance of my casual lovers has tended to be trans women largely owing to the resources of Craigslist, Grindr, and Scruff. Upon serious self-reflection, I will honestly say that I have never dated a trans woman only because she was trans. Humor, intelligence, political views, and character have always taken precedence for me above all physical attributes. If I were considering pursuing two women who both had an array of qualities I found attractive, and one of them was a trans woman, I would admittedly factor it in as an attribute that might tip the scale her way, but it would not be such an important factor that it would outweigh many other considerations about her personality and values.

Although I recognize my privilege as a cis man (a position I would like to approach with the utmost humility) I am not entirely content to concede the entire discourse of trans affinity to trans identified people because the discourse is occasionally referencing and judging my identity. And while I take in trans people’s perspectives, opinions, and arguments, they do not always accurately describe the nuances of my own experience. I want to hear trans identified people speak; but I would like to speak too. My debt to Avery Tompkins’ work on trans men and cis women is large. Of trans affinity, they write:

These discussions cannot be held without cis people. While I recognize the value in trans-only conversations and spaces, denying cis people the ability to take part in conversations around transsexualities seems detrimental to a sustainable sex-positive trans politics, especially if there are arguments circulating that cis people are doing the majority of the fetishizing or “tranny chasing.” Cis people are not inherently incapable of taking part in sex-positive and affirming discourse about trans identities and bodies, but they are certainly the individuals most at risk for being labeled “tranny chasers,” which may limit what cis partners and allies believe they can say about their attractions and desires. (2014: 775)

We have already seen the subjects of Tompkins’ study struggle to find suitable words to describe their relationships with trans partners. A compulsory silence limits the range of their amorous experiences to the drabbest shades of grey, cramming diversity into readymade hetero- or homo-normative binary categories. “Who tops and who bottoms?” is not a relevant question for understanding cis-trans (or any?) sexual relations. More precise language is necessary, and the fears of increased articulacy, in the face of magnifying potential offense, need to be assuaged.

This need for precision is evident when we examine the more hostile criticisms of transamorous people, such as we find in Princess Harmony’s 2016 article for The Establishment. Here Harmony categorically prohibits the use of any term that might mark an affinity for trans people. She writes, “Even the phrase itself—‘trans-attracted’—demonstrates how this fetish is inherently transmisogynistic. If those who identify with this label saw trans women as real women, they woul...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction: Outer and Inner Biographies of a Transam

- 1. Navigating the Seas of Identity: Can We Define the Transam?

- 2. Reframing Gender and Sexual Identities: The Buddhist Path and the Transam

- 3. The Quest for Validation: Giving Bodies Definition

- 4. Worlds of Interpretation: How Words Hurt Bodies

- 5. Against Interpretation: Liberating Bodies from Restrictive Languages

- 6. The Naked World: Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology of the Body without Interpretation

- 7. A Personal Transam Sexuality: My Body, My Words

- Endnotes

- Works Cited