- 360 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The classic text by renowned manga expert in a beautiful new casebound edition, with a new foreword and afterword by the author.

This landmark book, first published at the height of the manga boom, is offered in a hardcover collector's edition with a new foreword and afterword.

Frederik L. Schodt looks at the classic publications and artists who created modern manga, including the magazines Big Comics and Morning, and artists like Suehiro Maruo and Shigeru Mizuki; an entire chapter is devoted to Osamu Tezuka. The new afterword shows how manga have evolved in the past decade to transform global visual culture.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

ENTER THE ID

IN 1995, FORMER JAPANESE PRIME MINISTER KIICHI MIYAZAWA began serializing a column of his opinions, not in a newspaper or newsmagazine, but in the manga magazine Big Comic Spirits. A respected seventy-five-year-old politician and thinker, Miyazawa probably rarely reads comics,* but the reason he chose a manga magazine to air his views is clear. Big Comic Spirits is read by nearly 1.4 million young salarymen and potential voters each week. In today’s Japan, manga magazines are one of the most effective ways to reach a mass audience and influence public opinion.

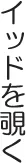

Japan is the first nation in the world to accord “comic books”—originally a “humorous” form of entertainment mainly for young people—nearly the same social status as novels and films. Indeed, Japan is awash in manga. According to the Research Institute for Publications, of all the books and magazines actually sold in Japan in 1995 (minus returns, in other words), manga comprised nearly 40 percent of the total.

Such industry statistics are indeed impressive, even frightening, but they hardly represent the entire picture or the true number of manga being read in Japan. There were 2.3 billion manga books and magazines produced in 1995, and nearly 1.9 billion actually sold, or over 15 for every man, woman, and child in Japan. Given the wild currency fluctuations of that year, the value of all comics produced ranged from U.S.$7–9 billion (a sum twice the GDP of Iceland), while those actually sold were worth $6–7 billion—an annual expenditure of over $50 for every person in Japan. Yet this does not include the millions of dōjinshi, or amateur manga publications, that do not circulate in regular distribution channels. Nor does it reflect the fact that non-manga magazines for adults, which used to be all text and pictures, now devote more and more pages to serialized manga stories. Finally, it does not take into account the popular practice of mawashi-yomi, of one manga being passed around and read by many people.

Manga share of all published books and magazines in Japan, 1995.

Statistics also do not indicate the huge influence manga have on Japanese society. Manga today are a type of “meta media” at the core of a giant fantasy machine. A production cycle typically begins with a story serialized in a weekly, biweekly, monthly, bimonthly, or quarterly magazine. The story, if successful, is then compiled into a series of paperbacks and deluxe hardback books, then produced as an animated series for television, and then made into a theatrical feature. For a particularly popular or long-running series, the cycle may be repeated several times. One manga story thus becomes fuel not just for the world’s largest animation industry, but for a burgeoning business in manga-inspired music CDs, character-licensed toys, stationery, video games, operas, television dramas, live-action films, and even manga-inspired novels.

At Japan’s largest and most prestigious publishers it is no secret that sales of manga magazines and books now subsidize a declining commitment to serious literature. Indeed, since manga are read by nearly all ages and classes of people today, references to them permeate Japanese intellectual life at the highest levels, and they are increasingly influencing serious art and literature. It is no exaggeration to say that one cannot understand modern Japan today without having some understanding of the role that manga play in society.

What Are Manga?

A LITTLE BACKGROUND

What are manga, exactly, and where did they come from? In a nutshell, the modern Japanese manga is a synthesis: a long Japanese tradition of art that entertains has taken on a physical form imported from the West.

* * * * *

In late 1994 I accompanied several well-known American comics artists to Japan for discussions with their Japanese counterparts. Will Eisner, the pioneer and reigning dean of American comic books, was along, and he was clearly shocked and puzzled at how popular comics are in Japan. After all, he himself had struggled long and hard to gain more recognition for comics in his own country. Yet when he took a long look at a display of 19th-century illustrated humor books in the Edo-Tokyo Museum, his face lit up in a satori-like realization of why Japanese so love comics: They always have.

Japanese people have had a long love affair with art (especially monochrome line drawings) that is fantastic, humorous, erotic, and sometimes violent. One of the most famous examples is the hilarious Chōjūgiga, or “Animal Scrolls,” a 12th-century satire on the clergy and nobility, said to be by a Buddhist priest named Toba. Today’s manga magazines and books, however, also have direct links to two types of entertaining picture books from the 18th and early 19th centuries—toba-e (“Toba pictures,” after the author of the “Animal Scrolls”) and kibyōshi, or “yellow-jacket books.” These were mass produced using woodblock printing and a division of labor not unlike the production system used by manga artists and their assistants today. Often issued in a series, again like today’s manga, they were beloved by townspeople in cities such as Osaka and Edo (today’s Tokyo). In a very real sense, they were the world’s first comic books.

The physical form of modern manga—the sequential panels with word balloons arranged on a page to tell a story—came from the United States at the turn of the century, when American newspaper comic strips like George McManus’s Bringing Up Father were imported. But unlike the United States, where slim magazines called “comic books” were first compiled in the 1930s from “comic strips” in newspapers, in prewar Japan the first real “comic books” for children were hardback books compiled from “comic strips” serialized in fat, illustrated monthly magazines for boys and girls. This pattern continues today in Japan; individual manga stories are usually first serialized along with many other stories in omnibus-style manga magazines and then compiled into their own paperback and hardback books.

WHAT MAKES JAPANESE MANGA DIFFERENT FROM OTHER COMICS?

The two predominant and most distinctive forms of comics in the world today are those of America and Japan; minor variations on both are found in Europe, Latin America, and Asia. Although they have an essentially similar format, Japanese and American comics have developed into two very different art forms. Other than the fact that manga are read “backward” because of the way the Japanese language is written, the most striking difference is size. American comic books are usually between 30 and 50 pages long, contain one serialized story, and are published monthly. But manga magazines, many of which are issued weekly, often have 400 pages and contain twenty serialized and concluding stories (some magazines have 1,000 pages and over forty stories); when an individual story is compiled into a series of paperbacks it may take up fifty or more volumes of over 250 pages each.

Prices of manga are also extraordinarily low, even given the dollar’s gutted value versus the yen in late 1995. Where a typical 32-page U.S. comic book (with many ads) cost over $2, a 400-page manga magazine rarely cost more than $3–4. On a per-page basis, therefore, the manga was six times cheaper than the U.S. comic book, a miracle made possible by the economies of scale Japanese publishers enjoy and by the use of low-quality recycled paper and mainly monochrome printing.

Manga magazines are not intended to last long, or even to be kept. Most are tossed in the trash can after a quick read, or recycled. Stories that are popular, however, are preserved by being compiled into paperback and hardback editions; most of the best comics in Japan—even those from forty years ago—are available in such permanent editions at a very reasonable price. As a result, Japan has largely been free of the disease from which American comics suffer: speculation. Collectors dominate the American mainstream comics market, and they are more likely to poly-bag their purchases and place them in a drawer than read them, thus driving up the price of both old and new comics. In 1995, one collector paid $137,500 for a copy of Action Comics No. 1, which first introduced Superman. As Toren Smith, a packager of Japanese comics in the U.S., notes, alluding to a company that produces coins especially for the collectors market, “many American comic book publishers have become the equivalent of the Franklin mint.”

Unlike mainstream American and European comics, which are richly colored, most manga are monochrome, except for the cover and a few inside pages. But this is no handicap when it comes to artistic expression. On the contrary, some manga artists have elevated line drawing to new aesthetic heights and developed new conventions to convey depth and speed with lines and shading. Using the “less-is-more” philosophy of traditional Japanese brush painting, many artists have learned to convey subtle emotions with a minimum of effort; an arched eyebrow, a downturned face, or a hand scratching the back of the head can all speak paragraphs. And since manga today are increasingly mass produced, artists can avail themselves of many new tools for quickly detailing monochrome backgrounds. The copy machine, for example, is often used by artists at high-contrast to incorporate photographs into backgrounds (in recent years some photographers have filed claims against artists for “appropriating” their images in this fashion). Another modern-day tool is “screen tones”—ready-to-use, commercially available patterned sheets that can be applied on a page to instantly create shadings and texture. Artists around the world use screen tones, but Japanese artists have access to such a variety that their overseas counterparts can only drool with envy. There are even screen tones for ready-made backgrounds of city- and seascapes. For those who prefer to draw by hand, there are special manga “background catalogs” with carefully rendered line drawings (available for copying) of the interiors of school classrooms, office rooms, train stations, restaurants, and other popular settings.

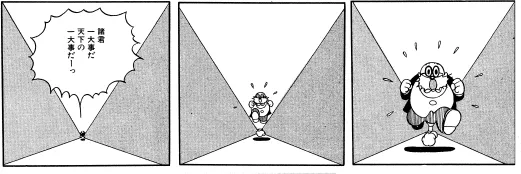

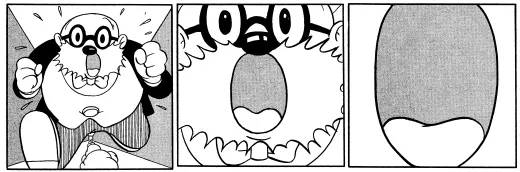

Cinematic effects, 1949. Panels from a page in Osamu Tezuka’s Metropolis, rearranged in left-to-right order to illustrate progression.

Still, many manga are quite poorly drawn by American and European standards. At the meetings held in 1994 between several noted American and Japanese comics artists, the Japanese boasted of the superiority of their form of comics—until it came to artwork, at which point they all looked rather sheepish and unanimously agreed that they could never match the draftsmanship of their Western counterparts.

The real hallmark of manga is storytelling and character development. After World War II, a single artist— Osamu Tezuka—helped revolutionize the art of comics in Japan by decompressing story lines. Influenced by American animation in particular, instead of using ten or twenty pages to tell a story as had been common before, Tezuka began drawing novelistic manga that were hundreds, even thousands of pages long, and he incorporated different perspectives and visual effects—what came to be called “cinematic techniques.” Other artists in America, such as Will Eisner, had employed cameralike effects a decade earlier, but combining this technique with the decompression of story lines was new

The result was a form of comics that has far fewer words than its American or European counterpart and that uses far more frames and pages to depict an action or a thought. If an American comic book might use a single panel with word balloons and narration to show how Superman once rescued Lois Lane in the past, the Japanese version might use ten pages and no words. (Of course, the monochrome printing, cheap paper, and the enormous economies of scale enjoyed by Japanese industry also make it economically possible for artists to do this.)

Many American artists have been heavily influenced by Japanese manga in recent years, so that some of the differences between the two art forms have begun to erode. But if one were to make a gross generalization, it would be that until recently many mainstream American comics still resembled illustrated narratives, whereas Japanese manga were a visualized narrative with a few words tossed in for effect.

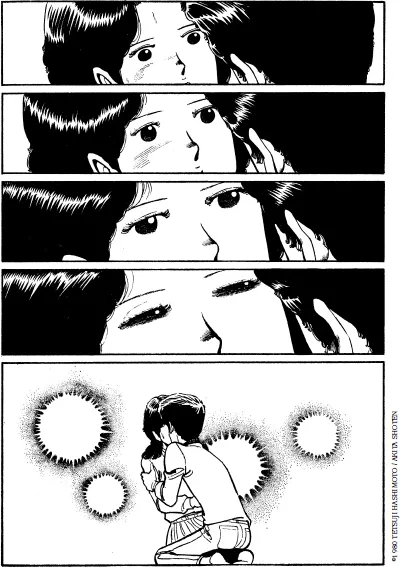

The cinematic style enables manga artists to develop their story lines and characters with more complexity and psychological and emotional depth. Like good film directors, they can focus reader attention on the minutia of daily life—on scenes of leaves falling from a tree, or steam rising from a bowl of hot noodles, or even the pregnant pauses in a conversation—and evoke associations and memories that are deeply moving. Japanese comics are perhaps unique in the world in that it is not unusual to hear fans talk about weeping over favorite scenes.

The cinematic style also allows manga to be far more iconographic than comics in America and Europe. Individual illustrations don’t have to be particularly wellexecuted as long as they fulfill their basic role of conveying enough information to maintain the flow of the story. And why should they be? A young American or European fan of comics may spend minutes admiring the artwork on each page of his or her favorite comic, but not the Japanese manga fan. As I wrote in 1983, to the amazement of many in the U.S. comics industry, a 320-page manga magazine is often read in twenty minutes, at a speed of 3.75 seconds per page. In this context, manga are merely another “language,” and the panels and pages are but another type of “words” adhering to a unique grammar. Japanese say that reading manga is almost like reading Japanese itself. This makes sense, for manga pictures are not entirely unlike Japanese ideograms, which are themselves sometimes a type of “cartoon,” or a streamlined visual representation of reality.

Japanese manga offer far more visual diversity than mainstream American comics, which are still shackled by the Greek tradition of depicting the human form and still reveal an obsession with muscled males and full-figured females. Only in American “underground comics” or “independents” can one find anything approaching the eccentricity of art styles that exists in Japan—where humans may be depicted in both realistic and nonrealistic styles in the same story, with both “cartoony” and “serious” backgrounds.

Cinematic effects, 1980. Tetsuji Hashimoto’s Itsumo Kimi ga Ita (“You Were Always There”).

The diversity of manga extends to subject matter. American and European comics long ago began dealing with very serious themes, thus making the ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Dedication

- Preface to the Collector's Edition

- Preface to the Original Edition

- 1 Enter the Id

- 2 Modern Manga at the End of the Millennium

- 3 The Manga Magazine Scene

- 4 Artists and Their Work

- 5 Osamu Tezuka: A Tribute to the God of Comics

- 6 Beyond Manga

- 7 Manga in the English-Speaking World

- Afterword: Whither Manga?

- References and Recommended Readings

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Dreamland Japan by Frederik L. Schodt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Animation. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.