eBook - ePub

Available until 30 Dec |Learn more

Innovating Out of Crisis

How Fujifilm Survived (and Thrived) As Its Core Business Was Vanishing

This book is available to read until 30th December, 2025

- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 30 Dec |Learn more

Innovating Out of Crisis

How Fujifilm Survived (and Thrived) As Its Core Business Was Vanishing

About this book

CEO Shigetaka Komori's own story of why Fujifilm succeeded where Kodak failed...

In 2000, photographic film products made up 60% of Fujifilm's sales and up to 70% of its profit. Within ten years, digital cameras had destroyed that business. In 2012, Kodak filed for bankruptcy. Yet Fujifilm has boasted record profits and continues strong.

What happened? What did Fujifilm do? What do businesses today need from their leaders? What kinds of employees can help businesses thrive in the future? Here, the CEO who brought Fujifilm back from the brink explains how he engineered transformative organizational innovation and product diversification, with observations on his management philosophy.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Innovating Out of Crisis by Shigetaka Komori in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

Fighting for Fujifilm

1

THE CORE BUSINESS VANISHES

WHAT HAPPENED AT FUJIFILM?

The transformation was coming, and it would be profound. It would disrupt our industry in the way that word processing disrupted typewriting, music CDs displaced records, and email dispatched the handwritten letter. Growing and accelerating like a snowball swelling to an avalanche, it was aimed right at us. In fact, our name put us in the crosshairs.

The transformation was digital photography, and we were Fujifilm.

The Coming Crisis

When I was appointed president of Fujifilm in 2000, sales of the company’s primary product line of photosensitive materials, notably our color photographic film, recognized around the world in its signature green boxes, had just about peaked. The following year, Fujifilm sales finally overtook those of the East-man Kodak Company, the industry giant, something we had been striving to do since our foundation. It was a corporate mission embraced by everyone at Fujifilm, and achieving our goal was a source of great pride.

The sales gap between the two companies as I signed on with Fujifilm at the beginning of the 1960s was immense and daunting. Kodak had more than ten times our revenues, and it took Fujifilm nearly forty years to catch up to our mighty monolithic rival. But we did, and our success was mighty in itself. By then, our market share in Japan alone was close to an overwhelming seventy percent.

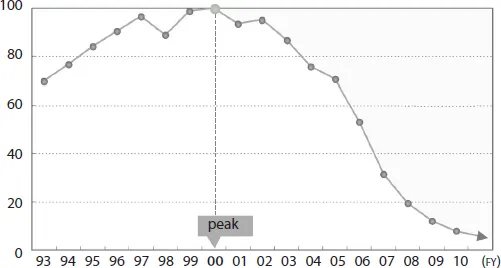

The peak of the industry coincided with our own peak—Fujifilm’s emergence as the worldwide market leader in photographic film. Yet, in an often unpredictable business world, a peak always conceals a treacherous valley. It soon became clear that we would preside in our leadership over a contracting market. Digital cameras were already spreading like wildfire, basically eliminating the need for film. After the industry’s sales peak in 2000, the film market began shrinking very slowly, then picked up speed, and finally plunged at the rate of twenty or thirty percent a year. Ten years later, worldwide demand for photographic film had fallen to less than a tenth of what it had been.

Total Global Demand for Color Photo Film (Y2000 represents 100)

This is how a battle began that I couldn’t afford to lose, a battle that I would throw myself into body and soul.

My task was to save the company.

Technology-Oriented Fujifilm

Fujifilm today is engaged in such a wide variety of businesses that it’s difficult to summarize everything we do. But you can say one thing with certainty: this company is technology-oriented.

Fujifilm was founded in 1934 with the mission to undertake the domestic production of photographic film. The need for high-quality water and clean air led Fujifilm to establish its factory and headquarters at the foot of Mt. Fuji in Minami Ashigara City, Kanagawa, Japan. Many product lines were developed at this location: photographic film and photographic paper, X-ray film, graphic arts film, PS (presensitized) plates, magnetic tape, related equipment, IT products, and more.

Japanese companies around this time assumed that establishing a new company or creating a new industry required importing technology from abroad. But at Fujifilm we decided to develop our own technology, and this meant the company had to clear a number of immense hurdles. The postwar transition of film from black and white to color was particularly difficult. Not only Fujifilm, but Kodak and other companies throughout the world were struggling with the development of this new technology.

There were at one time thirty or forty producers of monochrome photo and X-ray film in existence globally, among them some of the world’s most renowned chemical companies. But with the advent of color film, many of these companies were confronted by an insurmountable wall—the control of material and quality at a level of precision they could not meet—and they were forced to withdraw from the business.

After DuPont’s and 3M’s departure, the only firms left in the color film business were America’s Eastman Kodak, Japan’s Fujifilm and Konica, and Europe’s Agfa-Gevaert. The history of photographic film manufacturing thereafter rode on the rivalry among these four companies in quality control and technology.

The Kodak Giant

Kodak was head and shoulders above all the others in the manufacture of photographic film when I joined Fujifilm in 1963. At the time, Fujifilm had total sales of ¥27 billion, a figure dwarfed by Kodak’s nearly ¥400 billion.*

Then, of course, the difference between all Japanese companies and their American rivals—think Toyota and General Motors—was much the same story. And the difference was not just in sales. Kodak’s technology was also far ahead of Fujifilm’s. It was true as well of brand recognition and financials. The gap between these two rivals was simply enormous.

The year 1963 was only eighteen years after Japan’s defeat in World War II. Most Japanese at the time thought that American companies were invincible, that it was fruitless to even try to compete. At one point I heard something from a senior colleague that made my jaw drop. Large amounts of silver and gelatin are needed to manufacture photographic film, and my colleague told me that Kodak had its own silver mine and ran its own cattle ranch to secure a supply of high-quality gelatin from cattle bones! We might just as well have been taking a knife to a gunfight.

This was the situation when Fujifilm began its relentless pursuit of Kodak. Our corporate goal was to surpass Kodak—eclipse our Rochester, N.Y. rival—because it was the colossus of the industry. Despite the huge hurdles, we would be the giant slayer.

Fujifilm’s technology caught up with Kodak’s in the late 1970s, and by the 1980s we firmly believed we had technically surpassed Kodak in nearly all varieties of film. From the 1980s into the 1990s, we waged a persistent struggle with Kodak for world market share. And when we took the lead, it was not at all a Pyrrhic victory, even if worldwide film sales almost immediately began to fall.

It was, instead, the beginning of an unprecedented challenge.

First Attempts at Diversification

My first job at Fujifilm was in the Corporate Planning Division. As a young, untested executive, the only assignment I was given consisted of forecasting demand for photographic film. Desk work didn’t suit me, I found—I was just too ready for action, and I soon asked for a transfer to sales as a better channel for my pent-up energies.

Fujifilm at that time had a Consumer Photo Products Division, which was in charge of photography-related matters, and an Industrial Materials & Products Division, which handled photographic technology and other newly developed technologies for industrial use. I was assigned to the latter.

The company had set up the Industrial Materials & Products Division in 1961, a couple of years before I joined. But Fujifilm had already been involved in related areas, such as the development of X-ray film, since shortly after its founding in 1934, and had a history of leveraging its photographic technology to other products and markets to give its business activities a broader scope.

Photo film is made of a finely tuned combination of various basic technologies. For example, in color photography, an original color image is reproduced essentially by mixing the three primary color materials used in printing: cyan (C), magenta (M), and yellow (Y)—these are complementary to the three primary colors of light: red (R), green (G) and blue (B). But if the balance between them is even a little bit off, the photographic image of a white color shirt, for example, may have a red or bluish tinge when it is printed. Precise control of materials is essential to maintain a proper color balance in the reproduced image.

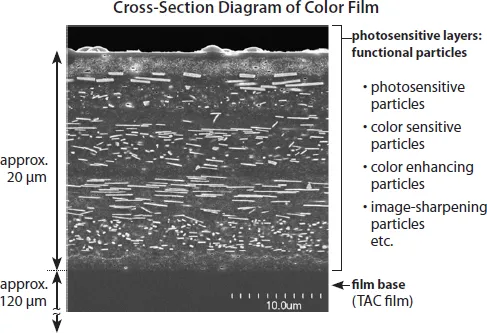

Look at a cross section of color film and you will see that on a clear base film there are twenty evenly coated layers, each sensitive to the three primary colors of light—red, blue, and green—that are perceived by the human eye. These overlapping twenty layers are no more than twenty microns in thickness. Thanks to high-precision coating technology, these light-sensitive layers are able to capture the faintest illumination, amplify it, produce color, and record an image. The reproduction of color in such thin layers is an amazing technical feat that was accomplished long before the semiconductor industry managed to squeeze ever more transistors on a chip. In fact Fujifilm today makes many products for that industry, too.

Various advanced technologies are required to manufacture photographic film. In addition to film formation and high-precision coating, there are grain formation, functional polymer, nano dispersion, functional molecules, and redox control (manipulating the oxidation of a molecule). Inherent in all these is very precise quality control.

It was only natural that Fujifilm would consider whether some of these technologies could be used in other ways. For example, instead of a film base, coatings of photosensitive material can be applied to aluminum plates, which are then exposed and developed so that lettering and graphic areas can be coated in ink to produce a master plate for printing. This is the so-called PS plate used in offset printing. By expanding on the technology of photographic film and replacing silver halide with magnetic powder as a base coating, it becomes possible to develop and produce audiotape, videotape, and computer memory tape.

At the time I joined Fujifilm, this type of diversification was already proceeding quickly. Understandably so, since it was during this period, too, that the import of photosensitive materials into Japan was being liberalized and custom duties were being lowered. This meant that Kodak, with its overwhelming technological lead and sales volume ten times that of Fujifilm, would soon be entering the Japanese market.

Preparing for the inevitable, Fujifilm threw itself wholeheartedly into developing photographic film products that could compete on an international level. We lowered costs by rationalizing our manufacturing processes. We also made plans to enter new fields of enterprise, leading to the establishment of the Industrial Materials & Products Division, to which I was assigned.

At the time, PS plates and associated products were new on the market, so when I visited a printing company it was not unusual for the printer to say, “Fujifilm, huh? What brings you here?” And I would say, “Well, it happens we have this product called a PS plate ...” I spent practically every day cold-calling on potential clients.

The biggest moneymaker for the company at the time, by far, was still the area of photography products, which was handled by the Consumer Photo Products Division. But it was the graphic-arts-related business of the Industrial Materials & Products Division that would later make a huge contribution to a sudden surge in our sales—and fortunes.

Overseas Development and Foreign Encroachment

In 1976, Fujifilm was the first company in the world to create high-speed color negative film with its development of F-II 400. This was an epoch-defining event that essentially meant Fujifilm had surpassed Kodak in technology.

Riding the momentum, Fujifilm launched an aggressive worldwide campaign in the 1980s, proclaiming its technologically sophisticated products under the slogan “Challenging the World with Our Technological Prowess.” Fujifilm built up its international manufacturing base and sales network and began to compete with Kodak in every corner of the world, establishing itself as a truly global enterprise. In 1984, Fujifilm became an official sponsor of the Olympic Games in Los Angeles, Kodak’s own U.S. backyard, and in other ways continued to bolster its marketing activities. We built a factory in the U.S. in 1988, and continued to grow our share of the American market.

This reversal of long-standing American and Japanese commercial positions was apparent in a number of other industries in the 1980s. Many Japanese enterprises caught up with and technologically surpassed their American counterparts and assumed superior competitive positions. In 1985, with much of the world feeling the threat of Japan’s growing industrial strength, the G5 nations (France, Germany, the U.S., the U.K., and Japan) gathered at the Plaza Hotel in New York City and drew up the Plaza Accord, which called for an adjustment in the currency exchange rate. This marked the first of many times, continuing to the present day, that Japan and Japanese industry have had to shoulder the burden and competition of a strong yen.

But this type of international pressure on Japan was not confined to the exchange rate. At about the same time the U.S. government began to apply successively more political pressure, through such collaborations as the U.S.-Japan Semiconductor Agreement and the U.S.-Japan Automotive Consultative Group, to force Japan to increase imports into its own domestic market.

Many of these political tactics were directed right at Fujifilm’s core business: photosensitive materials. In 1995, Kodak filed a petition with the Office of the United States Trade Representative arguing that Japan’s alleged exclusionary practices with regard to photographic film and paper had closed the Japanese market to competition to favor Fujifilm.

Fujifilm, under the direction of then-President Masayuki Muneyuki, produced a detailed rebuttal based on objective fact and categorically refuted the charges. In 1998, the World Trade Organization announced a sweeping rejection of Kodak’s complaints, giving Fujifilm the victory in this trade skirmish. This case was unusual for the time, showing that Japan could compete directly with foreign countries—and win. The victory was highly regarded in Europe and elsewhere, and Fujifilm’s presence rose in sales and stature in markets througho...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part One: Fighting For Fujifilm

- Part Two: Managing For Victory

- Conclusion