![]()

1

Duopoly and Its Challengers

When the variety and number of political parties increases, the chance of oppression, factionalism, and non-critical acceptance of ideas decreases.

James Madison

One of the best-kept secrets in American politics is that the two-party system has long been brain dead—kept alive by…state electoral laws that protect the established parties from rivals and federal subsidies and so-called campaign reform. The two-party system would collapse in an instant if the tubes were pulled and the IV's were cut.

Political scientist Theodore Lowi

The American party system is a duopoly, an enforced two-party system. For a century and a half, the Democrats and Republicans have dominated and shared the coveted center ring of American party politics. These two major parties fight over many things, but they have long been aware of their shared interest in mutual self-protection, in taking steps to shut out challengers to their exclusive places inside that center ring.

Over the last century, state and federal decision makers—Democrats and Republicans—have enacted and enforced duopolistic measures that stymie, disadvantage, or shut out the electoral initiatives of third parties and independents. The American political system has assumed many characteristics of a party state as a result.

Most Americans speak of their nation's party system as a two-party system. They might be surprised to know that this term was not even coined until 1911. Richard Winger, an expert on election law and a leading advocate for opening the election system to participation by minor parties and independent candidates, points out that the term two-party system was devised to mean “a system in which two parties are much larger than all the other parties. It doesn't mean a system in which there are just two parties.”1

Two-party systems are more compatible with democratic values than are one-party systems. Defenders of two-party systems also contend that they are better than multiparty systems at providing for stable government. If confirmed in fact, that might provide a plausible argument for the legitimacy of a two-party system, provided that the system develops and is sustained by the cultural characteristics of a nation or by institutional practices devised without the intention to discriminate. America's two-party system does not stand on its own, although there are many who contend that it would be capable of doing so.

At a conference held in Copenhagen at the close of the Cold War, the United States, Canada, and thirty-three European nations enunciated and committed themselves to a set of human rights, rule of law, and democratic principles.2 Among these Copenhagen benchmarks there are obligations to “respect the rights of citizens to seek political or public office…without discrimination” (Article 7.5), and to “respect the right of individuals and groups to establish, in full freedom, their own political parties…and provide them with legal guarantees to enable them to compete on the basis of equal treatment” (Article 7.6).

In party terms duopoly is a two-party system that is undergirded by discriminatory systemic measures designed to burden, disadvantage, or entirely shut out challenges to the major parties' lock on electoral politics. Democratic principles may receive better service from a duopoly than from a one-party regime; but the case cannot be made that duopoly meets, or that it even aspires to, such internationally recognized benchmarks of best democratic practices as those registered in articles 7.5 and 7.6 of the Copenhagen agreement. This should be seen as a real dilemma for the nation that considers itself—and sometimes is regarded by others—to be the world's leading democracy.

The American party system is often identified with those of Great Britain and Canada. The British and Canadian systems, like that of the United States, feature two prevailing national parties along with various regional and national third, or minor, parties. But there are important differences between the American party system and its Canadian and British counterparts.

Third parties are always present in British and Canadian parliamentary life. Britain's third parties won 86 of 650 parliamentary seats in 2010. One of them, the Liberal Democrats, then joined the major-party Conservatives in forming a coalition government. The leftist New Democrats captured 102 of 308 seats in the 2011 Canadian House of Commons elections. Though historically a third party, the NDP thereby actually replaced the Liberals as the official major-party opposition to Canada's ruling Conservatives.

British and Canadian laws on ballot access do not discriminate. Parliamentary candidates receive ballot placement in their districts by complying with reasonable and undifferentiated requirements: submission of a petition with a very modest specified number of signatures and payment of a filing fee. Britain and Canada set a standard for political stability, doing so without duopolistic rules for the protection of the major parties.3 Much the same could have been said a century ago about the nondiscriminatory nature of interparty relationships in the United States. That is not the case today.

Ballot-access requirements that American major-party decision makers legislate and enforce are so difficult, bewilderingly diverse from state to state, and costly to surmount that they stop many would-be third-party challengers in their tracks. Antifusion and sore-loser policies in force in most states protect the primacy of Democrats and Republicans. The federal program of public (taxpayer-supported) funding of presidential campaigns distinctly favors the major parties and their candidates. The same is true of the policies of some of the states that have instituted public funding of their statewide and legislative elections.

It is not unusual for many candidates, even some fringy ones, to participate in televised Democratic or Republican debates before or early in the period during which the major parties are holding primaries and caucuses leading toward the selection of the nominee for president. But for the general election, the bipartisan Commission on Presidential Debates sets the access bar so forbiddingly high that a minor-party or independent candidate almost never gets invited to take part.

Reforms have been proposed that could broaden representation and inject some democratic vigor into the election process. But some of these reforms pose a threat to the protected status of the two major parties, and many governing bodies dominated by Democratic and Republican decision makers have routinely ignored or refused to enact them.

The Fruit of Duopoly: Stability or Paralysis?

Apologists for the current American party system present grim scenarios of instability, even chaos, in selected cases involving multiparty politics: in Germany during the Depression, for example, or Italy after World War II. By contrast, they say, the American system has proven to be a paragon of consensus building and stability.

The historical record of interparty relationships during the Clinton, George W. Bush, and early Obama years suggest otherwise: zero-sum thinking and the filibuster threat, intractability on health care and other issues, a policy process swerving sharply away from bipartisan comity (except in preserving duopoly), paralysis and virtual gridlock. Though pork builds up cholesterol in the human body, members of Congress appear to assume that “pork” is a vital nutriment sustaining the body politic. Congressional business requiring bipartisan support routinely comes heavily larded.

A month and a half before congressional Democrats passed health-care reform without a single Republican vote, Tim Rutten of the Los Angeles Times observed that

it has been more than four decades since the Congress…has been able to muster the will to pass a major piece of social legislation. Not since 1965, when Medicare and the Voting Rights Act both overcame decades of opposition to become law, has Congress proved itself up to the task.

[Now] the chances of substantively addressing the regulatory breakdown that allowed Wall Street's irresponsible speculation to precipitate the worst financial crisis since the Depression seem to recede every day.

Dissatisfaction with both political parties runs deep.4

Indeed Americans have lost affection for their party system, if affection they ever had. Millions of voters now reject major-party labels, opting instead to identify as independents or even to document their affiliation with a minor party.5 Opinion polls conducted over the last two decades consistently reveal a loss of popular faith in the legitimacy of the party system. Consider, for example,

• a 1992 Washington Post poll, 82 percent of the respondents to which concurred that “both American political parties are pretty much out of touch with the American people”;6

• a 2006 Princeton Survey Research poll in which 82 percent declared that the nation's problems are beyond the capacity of the divergent, quarreling major parties to resolve and 73 percent expressed a desire for electoral options beyond those provided by the Democrats and Republicans;7

• a Zogby poll, taken in the summer of 2009, in which 58 percent of the respondents said that they believe the United States needs more than two major political parties.8

Many citizens understand the condition of the parties, and they realize that the party system falls far short of best democratic practices. Public opinion may be motivating and mobilizing those who want to construct a more inclusive and vigorously democratic political process by demolishing the duopolistic underpinnings that were designed to protect the major parties from challenges coming from outside the center ring.

Breakthroughs at the Polls

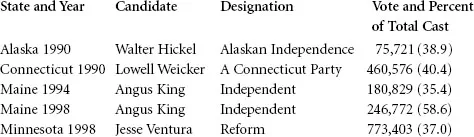

Early in the 1990s, a window of opportunity—the most significant since the Great Depression—opened for those who might challenge the lock held by the major parties on elections in America. The indications that this was coming already were surfacing by November 6, 1990. On that day two third-party gubernatorial candidates, Lowell Weicker of Connecticut and Alaska's Walter Hickel, were elected, and Bernard Sanders, running as an independent, won the lone Vermont seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. In victory all three had overcome both Democratic and Republican adversaries.

Weicker took the governor's office under a makeshift label: A Connecticut Party. (That A would give Weicker's party first place on the ballot two years later.) In three U.S. Senate terms, Weicker had been clearly identified with the progressive wing of the Republican Party. One of the accomplishments of his four years as Connecticut's independent governor was the establishment of a needed state income tax system.

Hickel ran as the nominee of the Alaskan Independence Party, but that party and its candidate were a mismatch from the start. He formally left the party near the end of his four-year term. Hickel had been an early champion of Alaskan statehood, and in Alaska and Washington, D.C., he had come to be known for his progressive environmentalist views. The Alaskan Independence Party's conservative positions on gun rights, home schooling, and other issues mirror the rugged individualism of Alaska's frontier. Founded in the 1970s, the party has long been identified with a secessionist vision of an independent Alaska. Its platform pushes the goal of a statewide referendum on the future status of America's largest state.

News of the Alaskan Independence Party again reached the lower forty-eight late in 2008, accompanied by a good bit of election-year chatter. It was reported that Todd Palin—Alaska's “First Dude,” the husband of Governor Sarah Palin, who was running for vice president with Arizona senator John McCain on a “Country First” theme—twice had registered with election officials as a member of the Alaskan Independence Party.

Sanders won Vermont's House seat in 1990 with a 56 percent share of the vote. Reelected seven times, he served Vermonters as their congressman from 1991 through 2006. In November 2006 Sanders won an open seat and a six-year term in the U.S. Senate, racking up more than 65 percent of the votes. Though running as an independent, he found allies among House and Senate Democrats, and he has affiliated with the Democratic conferences in the chambers where he has served.

As a public figure, Sanders clearly resides on the left. He is the only current member of Congress declaring himself to be a socialist.9 Late in the 2008 campaign, McCain and Palin began brandishing the s-word to drub Senator Barack Obama, their Democratic presidential opponent. Their charge usually was indirect, either quoting some remark made by “Joe the Plumber” or declaring that Senator Obama's voting record was even more liberal than the senator's who called himself a socialist.

Vermonters of course know of their independent senator's socialist claim. They also understand his connection to their state's Progressive Party. Before going to Congress, Sanders had served four terms (1981–89) as the mayor of Burlington, his rural state's largest city. In the early 1980s, Burlington progressives established their city's Progressive Coalition. They made Sanders its lead nominee and de facto leader.

A major party in city politics, Burlington's PC eventually went statewide, recasting itself as the Vermont Progressive Party. Progressive Anthony Pollina won a quarter of all votes cast for lieutenant governor in 2002 and 22 percent in his 2008 independent campaign for governor. Vermont's Progressives won thirteen state legislative elections in the 1990s and seventeen from 2000 through 2008.10 Theirs may be the most remarkable nonnational third-party success story of the last three decades.

Before the 1990 gubernatorial victories of Hickel and Weicker, just one candidate not running as a Democrat or Republican had won a state governorship in the years since the end of World War II. Three other such victories followed Weicker's and Hickel's in the 1990s. Running as an independent, Angus King, a well-known businessman and on-screen host on Maine public television, was elected governor of Maine in 1994 and won reelection in 1998.

Jesse Ventura was elected governor of Minnesota in 1998. Flamboyant in style, Ventura was a former professional wrestler and the past mayor of the Minneapolis suburb of Brooklyn Park. He had run as the nominee of the Reform Party, which Texas billionaire businessman Ross Perot had launched just three years before Ventura's Minnesota election victory.

Table 1.1 Victorious 1990s Third-Party and Independent Governors

Ross Perot and His Movement: The Center, with an Attitude

Few would have predicted it, but it was Perot who devoted his quirky appeal, immense wealth, and sheer grit to fostering and leading one of the most powerful twentieth-century assaults on the nation's duopoly. Remarkably Perot and his supporters—some called them Perotistas—defied the conventional wisdom that the brightest potential for a third-party movement lies either to the left or the right of both major parties. They built their movement squarely at the ideological middle.

Centrist though it was, this was a movement with an attitude, and it enlisted the support of millions who were “mad as hell” at all those inside-the-Beltway people who held the power. Micah Sifry, the author of an engaging book on recent third-party politics, dubbed Perot and his movement “the angry middle.”11

One very angry private citizen had in fact generated the wave on which the movement would ride. In 1990 retired businessman Jack Gargan drew up a mad-as-hell diatribe he titled “Throw the Hypocritical Rascals Out!” and then devoted his own money to getting it published as a full-page ad in six newspapers nationwide.12 Although Perot and Gargan often differed and eventually split, Gargan was the movement's original spark and an important factor in building it up.

Perot grasped the visceral feeling of millions of Americans that they were not being served by the two-choice menu of conservative Republicans and liberal Democrats. Perot was a centrist, but a militant one. Despite his wealth and connections, he carved out for himself the image of the archetypal Washington outsider. Given to populist speech and earthy sound bites, he vowed that he was going to “clean out the barn.”

Perot wanted balanced budgets, term limits, and a fundamental change in the way elections and campaigns are run in America. A trade-policy protectionist, he predicted that NAFTA—the North American Free Trade Agreement—would produce a “giant sucking sound” of American jobs being outsourced to Mexico. Perot's views on the global economy are reflected in some of the positions taken by today's antiglobalization activists on both right and left.

The accomplishments of Perot's 1992 bid for the ...