- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The definitive story of a South Carolina newspaper editor's murder at the hands of a 1902 gubernatorial candidate, and the dramatic trial that ensued.

On January 15, 1903, South Carolina lieutenant governor James H. Tillman shot and killed Narciso G. Gonzales, editor of South Carolina's most powerful newspaper, the State. Blaming Gonzales's stinging editorials for his loss of the 1902 gubernatorial race, Tillman shot Gonzales to avenge the defeat and redeem his "honor" and his reputation as a man who took bold, masculine action in the face of an insult.

James Lowell Underwood investigates the epic murder trial of Tillman to test whether biting editorials were a legitimate exercise of freedom of the press or an abuse that justified killing when camouflaged as self-defense. This clash—between the revered values of respect for human life and freedom of expression on the one hand and deeply engrained ideas about honor on the other—took place amid legal maneuvering and political posturing worthy of a major motion picture. One of the most innovative elements of Deadly Censorship is Underwood's examination of homicide as a deterrent to public censure. He asks the question, "Can a man get away with murdering a political opponent?" Deadly Censorship is courtroom drama and a true story.

Underwood offers a painstaking re-creation of an act of violence in front of the State House, the subsequent trial, and Tillman's acquittal, which sent shock waves across the United States. A specialist on constitutional law, Underwood has written the definitive examination of the court proceedings, the state's complicated homicide laws, and the violent cult of personal honor that had undergirded South Carolina society since the colonial era.

"Since the 1920s, the United States has had dozens of sensational trials—all of which have been labeled "the trial of the century." There is no question had the trial of Lieutenant Governor James Tillman for the murder of N. G. Gonzales, the editor of the State newspaper, occurred in our time that it would have had the same appellation. . . . Riveting . . . as gripping as any contemporary courtroom drama." —Walter Edgar, author of South Carolina: A History

"An insightful and in-depth look at the assassination of Columbia newspaper editor N.G. Gonzales by South Carolina Lt. Gov. James H. Tillman in 1903. Jim Underwood's carefully researched work not only reports on the killing and ensuing trial, it explains the forces that created a society where it was acceptable to kill a man to silence his pen." —Jay Bender, Reid H. Montgomery Freedom of Information Chair, University of South Carolina

"Finally, Jim Underwood has unraveled the killing, the murder trial, and the aftermath, and through his narrative tells a story of unfettered freedom of the press versus hot-bloodied Southern manhood honor. Without question, Deadly Censorship is a remarkable, eloquent, and important book." —W. Lewis Burke, Director of Clinical Legal Studies, School of Law, University of South Carolina

On January 15, 1903, South Carolina lieutenant governor James H. Tillman shot and killed Narciso G. Gonzales, editor of South Carolina's most powerful newspaper, the State. Blaming Gonzales's stinging editorials for his loss of the 1902 gubernatorial race, Tillman shot Gonzales to avenge the defeat and redeem his "honor" and his reputation as a man who took bold, masculine action in the face of an insult.

James Lowell Underwood investigates the epic murder trial of Tillman to test whether biting editorials were a legitimate exercise of freedom of the press or an abuse that justified killing when camouflaged as self-defense. This clash—between the revered values of respect for human life and freedom of expression on the one hand and deeply engrained ideas about honor on the other—took place amid legal maneuvering and political posturing worthy of a major motion picture. One of the most innovative elements of Deadly Censorship is Underwood's examination of homicide as a deterrent to public censure. He asks the question, "Can a man get away with murdering a political opponent?" Deadly Censorship is courtroom drama and a true story.

Underwood offers a painstaking re-creation of an act of violence in front of the State House, the subsequent trial, and Tillman's acquittal, which sent shock waves across the United States. A specialist on constitutional law, Underwood has written the definitive examination of the court proceedings, the state's complicated homicide laws, and the violent cult of personal honor that had undergirded South Carolina society since the colonial era.

"Since the 1920s, the United States has had dozens of sensational trials—all of which have been labeled "the trial of the century." There is no question had the trial of Lieutenant Governor James Tillman for the murder of N. G. Gonzales, the editor of the State newspaper, occurred in our time that it would have had the same appellation. . . . Riveting . . . as gripping as any contemporary courtroom drama." —Walter Edgar, author of South Carolina: A History

"An insightful and in-depth look at the assassination of Columbia newspaper editor N.G. Gonzales by South Carolina Lt. Gov. James H. Tillman in 1903. Jim Underwood's carefully researched work not only reports on the killing and ensuing trial, it explains the forces that created a society where it was acceptable to kill a man to silence his pen." —Jay Bender, Reid H. Montgomery Freedom of Information Chair, University of South Carolina

"Finally, Jim Underwood has unraveled the killing, the murder trial, and the aftermath, and through his narrative tells a story of unfettered freedom of the press versus hot-bloodied Southern manhood honor. Without question, Deadly Censorship is a remarkable, eloquent, and important book." —W. Lewis Burke, Director of Clinical Legal Studies, School of Law, University of South Carolina

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Deadly Censorship by James Lowell Underwood in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1.

AN EDITOR IS CENSORED

On Thursday, January 15, 1903, at 12:40 P.M., Lieutenant Governor James Hammond Tillman adjourned the South Carolina Senate, over which he presided. Just before 2:00, accompanied by two state senators who had no foreboding of what was to come, Tillman walked out of the capitol building and across Gervais Street. As they came abreast of a streetcar transfer station at the northeast corner of Main and Gervais Streets, Tillman encountered Narciso Gener Gonzales, editor of the State newspaper, walking toward him on his way to lunch at his home on Henderson Street. Gonzales was turning left (east) from Main into Gervais Street. Around him swirled the frantic activity of the transfer station, with streetcars arriving and departing and passengers scurrying to catch their rides. Across Gervais Street loomed the massive north façade of the State House, guarded by a tall, silent sentinel, a Confederate monument surmounted by the figure of a soldier poised as if he were searching for trouble on Main Street. On the northwest corner of Main and Gervais, across from the transfer station, stood the Columbia Theatre with its twin towers, one containing a “town clock” and both “topped by hemispherical cupolas.” This building was a frequent host to traveling performers and also provided space for city offices, which lined the front of the building on Main Street. It was often called the opera house or the city hall. The intersection was the busiest confluence of political and commercial activity in Columbia. It was an odd setting for what was about to happen.

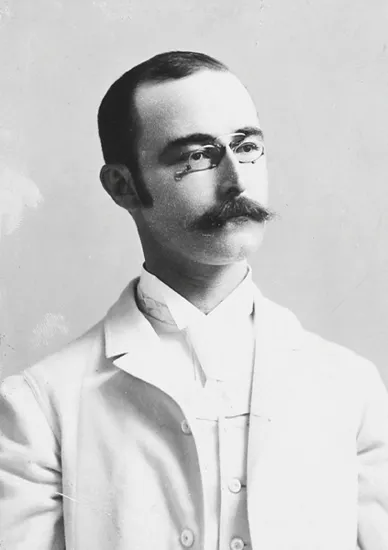

At forty-four Gonzales was a bespectacled, scholarly looking man with thinning hair combed close against his scalp and a luxuriant handlebar mustache, hinting that there were adventurous undercurrents to this mild-appearing man. Tillman was a much taller man of commanding presence set off by an impressively large head with theatrically chiseled bone structure. Tillman blamed Gonzales and his stinging editorials for costing him the governorship and causing his humiliating fourth-place finish in the first 1902 primary. He thought that in Gonzales’s hands freedom of the press had degenerated into a weapon of personal spite. Most of the leading South Carolina newspapers had opposed Tillman in the election, but the unsuccessful candidate focused his ire on Gonzales because his mocking words attacked the very marrow of Tillman’s personality.1

Narciso Gener Gonzales. Courtesy of the South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia, S.C.

Gonzales had repeatedly impugned Tillman’s honor by questioning his courage, his manliness, his honesty, and his veracity in ways that lowered his prestige and his status as a leader.2 In Tillman’s view a man was expected to defend his honor, not by a war of words, not by hiding behind the legal process in lawsuits, but by a direct, physical encounter. Unless he acted, more humiliation would soon follow. The next day, January 16, Tillman would face a deeply embarrassing situation. He would have to lead the Senate to a joint meeting with the House of Representatives at which the returns for the governor’s election would be examined and the winner proclaimed, forcing Tillman to participate in the public reopening of his wounds. In a few days he would have to watch another man, Duncan Clinch Heyward, be sworn in as governor, the office Tillman thought should have been his. Now here was the man responsible for humiliating him walking toward him. As Gonzales met up with Tillman’s group alongside the busy transfer station, Tillman pulled out a Luger pistol and shot Gonzales. Whether Tillman had cold-bloodedly attempted to put Gonzales off his guard by wishing him “good morning” just prior to shooting—and had cryptically told Gonzales “I received your message” just afterward—became the focus of intense disputes at Tillman’s trial. But one thing was certain: according to many witnesses, Gonzales’s dying declaration, and Tillman’s self-vindicating confessions, James H. Tillman shot N. G. Gonzales.3 Tillman fired one shot, but he was ready to fire again if Gonzales attempted to answer in kind. The wounded Gonzales clutched a transfer-station pillar for support, faced Tillman, and, according to his dying declaration, contemptuously said, “shoot again, you coward.” But one of Tillman’s companions, Senator Thomas Talbird, thought Gonzales said, “Here I am; finish me.” Any possible second shot was abandoned when Senator Talbird stepped between Gonzales and Tillman and said, “This thing must stop.”

Tillman fled the scene. He “sidestepped” across Main Street, dodging streetcars, stepping over the tracks, and keeping a wary eye on Gonzales. On reaching the northwest corner of Main and Gervais Streets, across from the transfer station and in front of the complex housing the city hall and the Columbia Theatre, Tillman was promptly arrested by policeman George Boland, who took Tillman’s weapon. Tillman pleaded that he should be given back his weapon so he could fight off the attack he claimed to expect from Gonzales’s supporters. He did not want to be “butchered”; he had heard that the State’s office had been turned into an “arsenal,” an armed camp from which reprisals could be launched. The request was refused.4 No such counterattack occurred. No gun was found on Gonzales, but at his trial Tillman testified that he had heard repeated reports in the days just before the shooting that Gonzales was armed and prowling the streets of Columbia looking for him.5 Witnesses disagreed as to whether Gonzales had made a gesture that could be interpreted as going for a gun, or had at most moved his hands further into his overcoat pockets to warm them against a cold January day, or had made no movement of his right hand at all. Witnesses also differed as to whether Gonzales, on approaching Tillman and his senatorial companions, had swerved to avoid a confrontation or had adopted a course that guaranteed one.6

View of the corner of Main and Gervais Streets in Columbia in 1905, looking north from the State House. Tillman shot Gonzales in front of the streetcar transfer station on the northeast corner at right. The City Theatre and city hall were in the building at left. Security Federal Collection. Courtesy of the Richland County Public Library.

After being shot, Gonzales staggered around the corner of the transfer station on to the Gervais Street side and then back to the Main Street side of the station, still sometimes hugging the building for support. Two bystanders, one on each side, took him in hand and helped him remain upright. Gonzales asked to be taken home to his wife. When no cab could be found, they helped him instead to walk back to the State newspaper office, which was in the same block of Main Street as the transfer station, where the shooting had occurred.7 At the office he was made as comfortable as possible, with a stack of newspapers serving as a pillow. Word of the tragedy spread quickly, a crowd gathered outside the paper’s office, and soon a bevy of doctors rallied to the injured editor’s side. He was taken to the hospital, where Dr. LeGrand Guerry and others performed an operation to repair the injury the shooting had caused to Gonzales’s large bowel. Gonzales lingered for four days. Despite the skilled and attentive treatment of the doctors, a septic infection set in and he died at 1:00 P.M. on January 19 from peritonitis. Prior to his death he made dying declarations (statements by one anticipating imminent death) that later became a focal point of bitter controversies during the trial of his assailant.

While Gonzales lingered near death in the hospital, Tillman lingered in quite a different style in the Richland County jail. A Charleston News and Courier reporter who visited Tillman found him “comfortably fixed” in a private room on the second-floor corridor.8 New furniture was moved in to replace the drab jailhouse decor.9 The atmosphere was brightened by “bunches of flowers” sent by his friends.10 An Atlanta Journal reporter visited Tillman at the jail and found that his second-floor room had “a bed and several chairs, [and] pictures [were] on the walls.”11 The prisoner’s wife, Mamie Norris Tillman, was permitted visits lasting several hours. Tillman was the nephew of United States Senator Benjamin R. Tillman, a powerful practitioner of hardball politics, and the son of Ben’s brother, the late congressman George D. Tillman, an influential political figure in his own right. Gossip abounded that Jim Tillman was receiving preferential treatment and was “faring sumptuously” in jail. The sheriff heatedly denied allegations of jailhouse high life. He was particularly incensed with charges that Tillman had unrestricted access to liquor and vowed to fire any jailer who permitted such a party atmosphere.12 While the sheriff fretted over criticism of Tillman’s comfortable incarceration, other officials began to investigate the killing.

The county physician moved swiftly, performing an autopsy at 4:30 P.M. on January 19, only three and a half hours after Gonzales’s death. On Thursday, January 22, an inquest jury at a hearing conducted by the county coroner found that “the deceased, N. G. Gonzales came to his death by a gunshot wound inflicted by the hand of James H. Tillman on the 15th day of January A.D. 1903.”13 This first official proceeding on the case attracted considerable interest. A reporter observed that there “were about a hundred citizens in the courtroom.”14 The investigation culminated in an epic trial that forced a choice between the values of freedom of the press and the sanctity of life on one side and on the other a belief that personal honor was such an essential ingredient of manliness that it justified violence to vindicate it.

Interwoven with the first steps of the justice system was the community grieving process. Gonzales’s funeral offered a solemn counterpoint to the investigation. In its somber pageantry and community-wide mourning, this event had some of the qualities of a state funeral. The last rites attracted so much attention throughout Columbia that they reinforced the defense attorneys’ perceptions that a Richland County jury would be hostile to the defendant and that they should thus seek to change the location of the trial to more friendly environs. The funeral was held at Trinity Church (now Cathedral) on Sumter Street in Columbia, across from the state capitol and near the corner of Main and Gervais Streets, where the killing had taken place. The church’s twin towers, each with eight pinnacles, added to the air of solemn dignity. The Tuesday, January 20, 4:00 P.M. service was conducted by Bishop Ellison Capers of the Episcopal Diocese of South Carolina, a former Confederate general and a longtime friend of N. G. Gonzales.15 He was assisted by the Reverend Doctor Samuel M. Smith of the First Presbyterian Church and the Reverend Churchill Satterlee, rector of the Trinity Church.16

Several pallbearers who had worked with Gonzales at the State carried a “floral tribute” that was arranged to represent the front page of the State, with flowers configured in such a way as to represent the paper’s colophon, “the palmetto tree, an emblem dear to the heart of the dead editor.” A headline composed of flowers stated, “N. G. Gonzales, Born 1858, Died 1903. The State Founded 1891.”17 The New York World described the wide variety of flower arrangements at the funeral, noting that “a floral tribute of more than ordinary significance came from the Negro porters of the Metropolitan Club, a proof of the gentle courtesy of Mr. Gonzales which endeared him to all classes of people with whom he came into personal contact.”18 News reports said there were so many “floral tributes” that local florists had to order flowers from out-of-town suppliers after the inventory in Columbia was exhausted.19 Beginning at 3:45 P.M., businesses closed throughout Columbia, including the textile mills, which rarely closed, even in dire emergencies. After the service at the church, a lengthy funeral procession traveled to the “Elmwood Cemetery as night was falling.” At this tranquil setting overlooking the Congaree River, Bishop Capers conducted the closing service as the “choir of Trinity sang ‘Jesus Lover of My Soul’ and other hymns.” In Charleston flags outside the offices of the News and Courier, for which Gonzales had been a reporter and Columbia bureau chief before he founded the State, stood at half-mast. Gonzales was survived by his wife, Lucy (or Lucie) Barron Gonzales, described as a “charming,” “civic minded,” “former state librarian,” whom he had married in 1901, when he was forty-three. Her mourning must have had added poignancy because their only child, Harriett (or Harriott) Elliott Gonzales, had “died shortly after birth.”20

The services were well attended even though one account described the day as “black and cold, a misty rain falling and freezing as it fell.”21 The large sanctuary at Trinity Church was completely filled, and an overflow crowd of several hundred gathered outside. One observer concluded that “with the exception of that of General Wade Hampton, it was probably the largest funeral assemblage seen in South Carolina in many years and the most representative.” Many state officials, including outgoing governor Miles B. McSweeney, attended. Organizations of which Gonzales had been a member, such as the Metropolitan Club and the Knights of Pythias, marched as a group in the long procession to the interment at the cemetery.

In addition to the local sentiment evidenced by the funeral, the killing was taking on a wider significance. The New York World was treating it as a blow against freedom of the press with implications throughout the country. If a crusading newspaper voice could easily be silenced by gun-barrel censorship, editors everywhere could grow timid, and the high officials who might otherwise fear newspaper scrutiny and act with restraint, would grow more arrogant. The World published an editorial cartoon titled “A National Crime.” It shows an assassin with a smoking pistol fleeing the scene of a shooting, leaving a crumpled body in the street. The hand of the body clutches a newspaper labeled, “The State, Columbia, S.C.” The killer is escaping around the corner of a building on which is written in large letters: “Liberty and Freedom of the Press.” The cartoon was not meant to be a literal depiction of the crime, but a symbolic representation of what the paper thought was a serious...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1. An Editor is Censored

- 2. Pretrial Maneuvers

- 3. The First Round of the Trial

- 4. The Prosecution Case

- 5. The Defense Case

- 6. Tillman’s Testimony

- 7. The Closing Arguments

- 8. The Verdict

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index