![]()

Chapter 1

A POLITICAL BULLRING, 1891–1916

Politics since the early colonial days have been the South Carolina bull ring. The passions profitlessly expended in it if turned into other energies might have produced a great literature or a triumphant industrial civilization.

—David Duncan Wallace,

History of South Carolina (1934)

Professor Wallace’s description of the role politics have played in South Carolina history was certainly appropriate for the years between 1891 and 1916. Few periods in the state’s history have seen as much political activity.

Politics were entertainment in turn-of-the-century South Carolina. In 1909 Governor Martin J. Ansel spoke in Georgetown. Courtesy South Caroliniana Library.

Facing a changing world, a world in which their state was considered less important than most backwater European colonies, white South Carolinians struggled among themselves for control over their changing society. Agriculture was depressed. Textile mills appeared all across the Piedmont, creating a new business-oriented elite and a white working class. Railroads turned country crossroads into market centers which, in turn, gave rise to the growth of a solid middle class.

These simultaneous alterations in South Carolina’s economic and social fabrics led to political instability. The old, pre-Civil War elite which had reestablished its control over the state in 1877 was out of touch and incapable of dealing with the situation. Farmers, mill workers, and middle-class reformers saw opportunities for their respective causes and for a quarter century vied for control of state and local governments.

SOME BACKGROUND: THE UNITED STATES IN 1890

In 1890, across the country, there was discontent with governmental and economic institutions. Since 1887, farmers in the South and the West had battled drought, low prices, and debts. There was more labor unrest in 1890 than in any other year in the century, although the violent Homestead and Pullman strikes were still a few years off.

The Panic of 1893 added to the nation’s economic woes. By the end of the year four million American workers were jobless. In an attempt to stabilize the economy, President Grover Cleveland asked J. P. Morgan to market government bonds and Congress to repeal the Sherman Silver Purchase Act.

Farmers felt betrayed. The President had sold out to “Wall Street,” which they considered the root of all that was wrong with American society. They were incensed by reports in the popular press of new millionaires’ conspicuous consumption. While tens of thousands of hard working men and women were losing their farms to banks, nouveaux riches built multi-million-dollar “summer cottages” at Newport. Something was wrong. Thomas Jefferson’s yeoman farmer no longer seemed to matter to the nation’s political parties. In frustration, voters in the West turned in 1892 to the People’s Party.

Four years later, southern and western farmers seized control of the Democratic Party, denounced Cleveland, and co-opted the Populists’ revolutionary platform—all to no avail. Bryan was defeated, and the political victory of business and industry over agriculture did little to solve the country’s problems. Reform-minded citizens began to work together to improve their communities. Eventually their determined efforts, fueled by the venal excesses of the Gilded Age, would lead to the Progressive Era and major national reforms.

SOUTH CAROLINA IN 1890

As South Carolina entered the last decade of the nineteenth century, its politics were just as unsettled as those of the rest of the nation and the reasons for the state’s political unrest were similar to those elsewhere.

Observers described the state and its people in less than flattering terms. Some of the negative comments came from northerners still getting in their licks for the state’s role in the secession crisis; however, among the chief critics of the “state of the state” were some of its native sons.1 They denounced the general lethargy that was a way of life for many South Carolinians.

Poverty and ignorance were cited as causes of the state’s woes, but were they the cause or were they the effect? One of the nation’s wealthiest states in 1860, South Carolina ranked near the bottom in per capita income in 1890.2 Poverty and debt were very real. In the late 1880s Carolinians forfeited more than one million acres of land for nonpayment of taxes.3 Debt was a crushing burden to those who tilled the soil. In any given year, 30 to 60 percent of the cotton crop was obligated for debt payments prior to harvest.4

In a vain attempt to increase their incomes, farmers planted more cotton. Subsistence farming was abandoned. Cotton production was twice what it had been in 1860, but increased cotton production across the South caused prices to plummet.5 Railroad rates were outrageous and designed to funnel South Carolina produce directly to northern markets rather than through Charleston. For example, it cost $0.46 to ship a bale of cotton from Abbeville to New York City, but $1.50 to ship one from Abbeville to Charleston.6

Illiteracy was a scandal. And so was public health—or the lack thereof. With 45 percent of the population totally illiterate, it should be no surprise that the state’s poor suffered from a variety of diseases.7 The young men of South Carolina were in such poor physical condition that rejection rates for white volunteers during the Spanish-American War would run as high as 44 percent in some upcountry counties.8 The condition of the state mirrored that of many of her people. South Carolina was in wretched shape economically. The Civil War was blamed for the state’s difficulties, but, in reality, the war simply had exacerbated problems that had existed since the 1820s.9

By the 1890s, South Carolinians produced three times as much cotton as they had in 1860. Georgetown’s docks were a busy place during the late fall. Courtesy South Caroliniana Library.

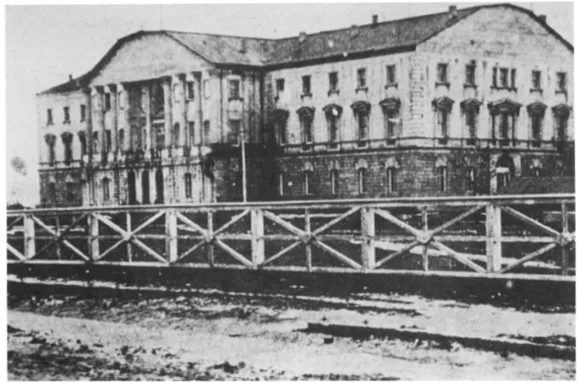

The unfinished State House, “a roofed over barn,” symbolized the poverty into which South Carolina had fallen after the Civil War. Courtesy South Caroliniana Library.

State government did little to assist the farmers. In fact, state government did very little at all. The inaction of those in office was due, in no small part, to their reaction to the excesses of the Reconstruction regime they had overthrown in 1877.10 To observers this lethargy (a few cruel ones called it atrophy) permeated South Carolina from top to bottom. Appearances, however, can be deceiving.

The state was on the verge of entering a turbulent quarter century (1891–1916) in which traditional beliefs and institutions would be challenged, altered, and, in some cases, discarded. South Carolina’s government, economy, and society would all undergo fundamental changes. The South Carolina that emerged from these twenty-five years of turmoil would survive intact into the 1960s.

Those in power, the old pre-Civil War elite, were out of touch with the general population. To their friends, they were “the Redeemers,” the men who had saved South Carolina from the horrors of black and Republican rule. To their enemies, they were “the Bourbons,” akin to the restored monarchists of nineteenth-century France who had forgotten what had caused their downfall and repeated their mistakes.

Regardless of the labels, they were, for the most part, older men who did not understand the problems facing the state. For them, it was enough to campaign as a war hero of ‘65 or a Red Shirt of’76.11

Although Tillman denounced the state’s old guard politicians (most of whom were Confederate veterans), individual Confederate veterans were still treated as heroes. In May 1910 veterans posed in front of the State House. Courtesy South Caroliniana Library.

To the discontented farmers, struggling to hang onto their debt-ridden farms, past glories didn’t help feed or clothe their families. Collapsing farm prices, worn-out soils, exorbitant credit rates (as high as 100% in some counties), and the Bourbons’ policy of racial moderation led to considerable discontent among rural whites. What the disgruntled farmers needed was a spokesman.12

THE RISE OF BEN TILLMAN

In 1885, after a fiery speech in Bennettsville before a joint meeting of the state Grange and the South Carolina Agricultural and Mechanical Society, the farmers found their leader: Benjamin Ryan Tillman of Edgefield County. Tillman electrified his audience by attacking the state’s “do nothing” leaders; however, he offered some positive recommendations as well. Chief among his proposals was the creation of a separate agricultural college for the sons of “real farmers.” The proposal for an agricultural college became the highest priority of the Farmers’ Association, a new group formed specifically to promote Tillman’s ideas. Very quickly the nonpartisan association became a vehicle for Tillman’s political ambitions.

The idea for another state-supported school was opposed vigorously by friends of the Citadel, the University of South Carolina, and South Carolina’s numerous denominational schools. It appeared that the proposal would get nowhere, but then Thomas G. Clemson died and willed his upcountry estate and $80,000 to the state of South Carolina for the purpose of establishing an agricultural college. The issue was joined. After furious debate, the General Assembly in 1889 voted to accept Clemson’s gift. USC’s College of Agriculture was closed and Morrill Act funds wer...