![]()

Under a Red Flag

“This is my work. As a wildlife biologist, I’m making a difference…. It makes me feel good.”

Pat Ferral

IN THE 1920S THE U.S. GOVERNMENT, along with the states of Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, and South Carolina, were hot to stamp out the “estimated 200,000 woods fires [that] burned annually in the South.” Believing fire to be “the greatest deterrent to renewed timber stands and to permanent forest management,” state governments dispatched fleets of trucks equipped with generators, movie projectors, and screens to show films such as Trees of Righteousness, which caricatured some southerners as Burnin’ Bills who “practiced the old southern custom of burning woods.” Playing at schools and fairs, the films were a successful if misguided attempt to “enlighten” rural folks about the evils of all forest fires.1

Bad science weighed in with those who distrusted fire. In the late nineteenth century most foresters “regarded fire as the unrelenting enemy of forest regeneration,” even going so far as to insist that in North Carolina, “the burnings of the present and future, if not soon discontinued, will mean the final extinction of the longleaf pine in this state.”2

Fire, however, had shaped the New World long before man—Native American or European—arrived. “Before the immigration of Indians into the Southeast near the end of the Wisconsin glaciation some 12,000 to 13,000 years ago, essentially all fires would have been caused by lighting…. The emerging picture suggests that terrestrial vegetation has evolved with fire from its very beginning in the early Devonian Era, some 400 million years ago.”3

Whether the early southerners mimicked nature’s processes or copied the Native Americans’ use of burns is up for grabs, but apparently the custom of setting fire to the woods was not imported to America by settlers from England. “A British traveler in South Carolina in 1829 was astonished to discover a recently burned stand of longleaf pine: ‘There was no underwood properly so-called, while the shrubs had all been destroyed a week or two before by a great fire. The pine trees, the bark of which was scorched to a height of about 20 feet, stood on ground as dark as if it had rained Matchless Blacking for the last month. Our companions assured us that although these fires were frequent in the forest, the large trees did not suffer. This may be true, but they certainly did look very wretched, though their tops were green as if nothing had happened.’”4

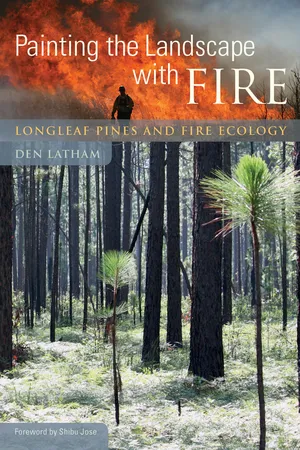

A prescribed burn. Converging lines of fire are set with drip torches or the aid of a helicopter and an aerial ignition machine. The intensity of the prescribed burn may be controlled by altering the distance between lines of fire.

Photograph by the author.

Before Europeans arrived in the New World, the humans already here had managed much of America’s forests and grasslands with fire, and not just in the Southeast. In the Northeast in the mid-1600s Adriaen van der Donck, a Dutch settler in the Hudson River Valley, wrote that the Haudenosaunee burned “‘the woods, plains, and meadows’ to ‘thin out and clear the woods of all dead substances and grass.’”5 In the Southeast, “Accounts from the Colonial Period describing Indian burning practices indicate that use of wildfire … peaked in fall and winter when fires were set to drive game.”6

Most hunters and hikers will find the image of precolonial America as a wildlife preserve ecologically advanced and a lot of fun. In 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus, Charles C. Mann expands on the idea of Native American as caretaker:

Rather than domesticate animals for meat, Indians retooled ecosystems to encourage elk, deer, and bear. Constant burning of undergrowth increased the numbers of herbivores, the predators that feed on them, and the people who ate them…. Incredible to imagine today, bison roamed from New York to Georgia. A creature of the prairie, Bison bison was imported to the East by Native Americans along a path of indigenous fire, as they changed enough forest into fallows for it to survive far outside its original range. When the Haudenosaunee hunted these animals, the historian William Cronon observed, they “were harvesting a foodstuff which they had consciously been instrumental in creating. Few English observers could have realized this. People accustomed to keeping domesticated animals lacked the conceptual tools to recognize that the Indians were practicing a more distant kind of husbandry.”7

Twentieth-century foresters, however, were slow to pick up the torch. In the 1920s a conservationist as progressive as Aldo Leopold derided the use of fire by Native Americans as “Piute Forestry” and its proponents as “propagandists”: “It is, of course, absurd to assume that the Indians fired the forests with any idea of forest conservation in mind.” Leopold did grasp one core concept of prescribed burns: “Light-burning means the deliberate firing of Forests at frequent intervals in order to burn up and prevent the accumulation of litter and thus prevent the occurrence of serious conflagrations.” Early in his career, however, he failed to grasp other key concepts and argued, “Light-burning gradually reduces the vitality and productiveness of the forage.”8 Leopold, writes Curt Meine, “had been conditioned to a simple response: fire was evil.” By 1923, however, Leopold showed sparks of recognition regarding the regenerative role of fire in forestry. He “still regarded fire as ‘the scourge of all living things,’ but admitted that forest fires sometimes caused an increase in vegetation beneficial to game.”9

For nearly a century the government’s wholesale suppression of fire was a death knell to many natural ecosystems. Despite the executions of this misguided policy, however, there were still intelligent, observant voices crying out in the wilderness. As early as 1913 Roland Harper, a forward-thinking botanist for the Geological Survey of Alabama, argued that “it can be safely asserted that there is not and never has been a longleaf pine forest in the United States … which did not show evidence of fire, such as charred bark near the bases of the trees; and furthermore, if it were possible to prevent forest fires absolutely, the long-leaf pine—our most useful tree—would soon become extinct.”10

In the last decades of the twentieth century, the winds shifted. Recognizing the role of fire in maintaining southern pine forests, the powers that be made a U-turn. The new road, however, is thorny and contentious, complicated by the encroachment of smoke into the suburbs and suburbs into the wildlands. Not surprisingly liability costs and lawsuits have increased.

Forester Pat Ferral of Ferral Environmental Services troops through these hot issues holding a drip torch in one hand and a briefcase stuffed with college degrees, petitions, legislation, insurance policies, high-tech gadgets, data, weather reports, and fire prescriptions in the other. He works to enlighten the public and restore the tradition of setting fire to the woods.

IT WAS A MORNING IN MID-MARCH, and there had been no rain in recent memory. The forecast was for a cold front to move in the next day and drop the temperature into the unseasonably low 50s. But this day would be blueskyed, dry, and in the 70s. A Category 5 day. A perfect day to set fire to the woods.

“I’m aware we’ve been under a red flag,” Pat Ferral had said over the phone the evening before, “but that’s not a burning ban, and we’re burning a safe area,” a tract of loblolly pines. “If the weather doesn’t change, expect a call from me dark-thirty tomorrow morning to confirm.”

Issued by the state Forestry Commission, a red flag fire alert is “a wildfire danger warning” that “asks people to postpone burning” but “does not prohibit outdoor burning as long as all other state and local regulations are followed.”11 A burning ban, in contrast, is a legal prohibition.

I had witnessed big, all-day burns of hundreds of acres at the Carolina Sandhills NWR; but because Ferral Environmental was burning a small tract, I expected an uneventful burn. Instead I got a hands-on lesson in what could go right and what could go wrong.

Pat met me at a Citgo station off I-20. I left my Jeep there and rode with him in a red F-150 to an expansive horse ranch, a thousand acres of rolling pastures, white fences, and pine stands in the upper coastal plain. The landowners were the CEO of an international firm and his wife, who raised thoroughbreds. They lived in Pennsylvania and jetted down to South Carolina on weekends “to hunt and relax,” Pat said. He had worked for these clients about six years.

Pam, Pat’s wife, waited for us at the ranch’s equipment shed. The two ran their environmental service out of Camden, South Carolina. Both were dressed in Nomex pants and green Nature Conservancy T-shirts.

Pat has degrees in natural science, biology, and forestry resources from Winthrop and Clemson Universities. “Worked at the Savannah Ecology Lab for a while,” he said. “Took a job with the state as a botanical technician. Did my master’s on red-cockaded woodpeckers.” Pam has a master’s in wildlife management from North Carolina State.

I asked about the T-shirts.

“I went to the Nature Conservancy fire schools,” he said. “For six years I monitored red-cockaded woodpeckers for them on Sandy Island.” (Located in the Waccamaw National Wildlife Refuge, Sandy Island is the largest undeveloped freshwater island in the eastern United States.) Pam had worked for the Nature Conservancy as a project director in Winyah Bay, South Carolina, and later as director of science and stewardship.

After lowering the tailgate of the truck, the two began filling pillow-size yellow bladders with water from a garden hose. Each rubber bladder held eight gallons (about sixty-seven pounds) of water and was fitted with shoulder straps and a hose. Pat called the bladders “backpack pumps.” In the event of a spotover—that is, if flames leaped across a firebreak—a crew member could shoulder the bladder and “attack the fire with backpack pumps and hand tools, squirt it with water, throw dirt on it with a shovel. But we’re not expecting any spotovers,” he added.

Pat also represented the Association of Consulting Foresters to the South Carolina Fire Council. The previous fall I had attended a meeting of the S.C. Fire Council in Columbia. The chief topic had been liability. I asked Pat about it.

“Liability’s our biggest problem. We’re trying to make changes at the state level to address it. We want to change ‘negligence’ to ‘gross negligence.’” The Florida legislature, he said, had already instituted the change.

I later asked Mike Baxley, judge of the Fourth Circuit in South Carolina, about the legal definitions of negligence and gross negligence. Simple negligence, he said, is the failure to use due caution or reasonable care. Gross negligence is when one acts with a reckless, willful, and conscious disregard for the rights and safety of others. Under South Carolina law, negligence can give rise to actual damages, whereas gross negligence can give rise to not only actual damages but also exemplary and punitive damages. Judge Baxley added that it was not unusual for an industry or profession to petition the General Assembly for protection from litigation.

“The threat of liability is one reason why there hasn’t been enough fire on the ground,” said Darryl Jones, forest protection chief for the South Carolina Forestry Commission and chairman of the S.C. Prescribed Fire Council, in a September 2012 interview.

For years the S.C. Prescribed Fire Council, supported by the Wildlife Federation, the Nature Conservancy, and other conservation groups, petitioned South Carolina’s legislature “to improve the legal climate for burning,” Darryl said. In the spring of 2012 they succeeded. The amended law states that if a certified prescribed fire manager is on-site supervising the burn, writes and follows a prescribed fire plan, and properly notifies the Forestry Commission, he gains legal protection. Liability relating to fire—for example, if a prescribed fire escapes and burns a neighbor’s house—still falls under simple negligence. But liability related to smoke—for example, if smoke from a smoldering fire obscures a road and causes an accident—now falls under gross negligence. “Once smoke is up in the air, it’s harder to control,” explained Darryl.

“This is a significant improvement to the law,” he stated. “It makes it easier for us to encourage burning. If weather cooperates, in years to come we expect to see an increase in the number of acres burned.” He added that “the state has never restricted the right of a landowner to conduct burns. You don’t have to be a certified prescribed fire manager to burn, but only certified burners are eligible for added legal protection under the Prescribed Fire Act.” The Forestry Commission offers training and certification for prescribed fire managers. In 2012 there were about fifteen hundred certified prescribed fire managers in South Carolina. “Already, the number of applicants for certification has gone way up.”

Done filling the water bladders, Pat and Pam began pouring slash fuel from a ten-gallon plastic can into drip torches. We continued talking about liability. “State and federal agencies want to increase the number of burns, but it’s increasingly difficult to afford insurance. My insurance has jumped eight hundred dollars this year because I do a lot of b...