![]()

Chapter 1

“An ornament to his country”

Early Life in Charleston

Less than a century before the American Revolution, the Laurens family migrated to the New World. Arriving first in New York before moving to Charleston, South Carolina, the Laurenses, over the course of three generations, achieved a prominent place in provincial society. André Laurens, his son Jean, and grandson Henry adhered to the Huguenot tradition of industriousness and enterprise that had produced so many important businessmen in their native, Catholic France. John Laurens’s hardworking and public-spirited ancestors laid the groundwork for him to play a conspicuous role in the Revolution.

Like other Huguenots, the Laurenses left France in the wake of Louis XIV’s efforts to stamp out Protestantism. André Laurens first moved to England, before deciding to try his fortunes in America. He and his wife Marie emigrated to New York, where many Huguenots had already settled. On 30 March 1697 Marie gave birth to the third of their five children, Jean Samuel. While in New York, the Laurenses befriended another family of Huguenot refugees, the Grassets. Jean Laurens married Esther Grasset shortly before André Laurens decided to uproot his family again. In 1715 the Laurenses, for a second time following in the footsteps of other Huguenots, sailed to Charleston, South Carolina. Charleston served both as provincial capital and center of economic life in the low country, the swampy coastal region of tall oaks, scrub pines, and rice plantations. The South Carolina low country’s economy stood on the verge of an expansion, fueled by the demand for rice and, in later years, indigo, that eventually made some of its white residents among the wealthiest people in the British North American colonies. Industrious and enterprising individuals could prosper in this setting.1

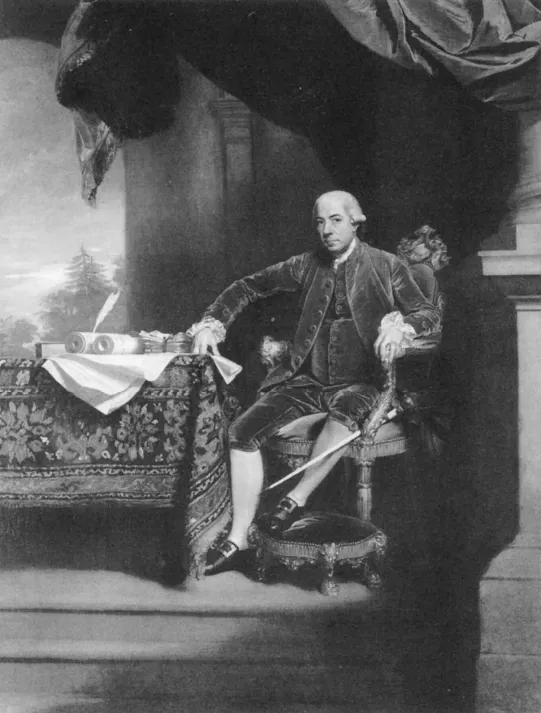

Portrait of Henry Laurens as president of the Continental Congress.

Painted by John Singleton Copley in 1782. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

André Laurens died soon after arriving in Charleston. He “had Saved So much Money as enabled him” to provide his five children “with Such portions as put them above low dependance.” As Henry Laurens, the son of Jean Laurens, later recalled, “Some of them retained the French pride of Family, & were content to die poor. My Father was of different Sentiments, he learned a Trade, & by great Industry acquired an Estate with a good Character & Reestablished the Name of his Family.”2

Jean Laurens, or John, as he was called, became a saddler. Over time he prospered in his trade and invested in real estate. Like most Huguenots, he quickly assimilated into Charleston society, the Anglicization of his name being one step in the process. He also joined the colony’s established Anglican church, where he served as warden of St. Philip’s Parish, and he owned at least five slaves. Yet he remained ambivalent toward the institution that formed the basis of South Carolina’s prosperity. On one occasion, he made a cryptic prediction that slavery would eventually collapse.3

John and Esther Laurens had five children who lived to maturity: Mary, Martha, Henry, Lydia, and James. Their eldest son, Henry, was born on 6 March 1724. Little is known of Henry’s early years. His closest friend was Christopher Gadsden, who was eight days older. The two companions “encourage[d] each other in every virtuous pursuit, to shun every path of vice and folly, to leave company whenever it tended to licentiousness…. By an honorable observance of a few concerted rules, they mutually strengthened virtuous habits.”4 Their behavior was a model of moral virtue; Henry Laurens adhered to these rules his entire life.

On 3 April 1742, less than a month after Henry’s eighteenth birthday, his mother died. Three months later his father married Elizabeth Wicking, a native of England. Henry’s reaction to his father’s precipitate remarriage was not documented. Shortly before the wedding, John announced his retirement.5

John Laurens “gave his Children the best Education” available in Charleston. Like other parents throughout history, John hoped his children would advance beyond the foundation he established for them. He decided that Henry, who was destined to be a merchant, should journey overseas to receive further training. About 1744 John sent Henry to London to work in the counting house of the respected merchant James Crokatt. In 1747 Henry finished his apprenticeship and returned to South Carolina.6

When Henry landed at Charleston on 3 June 1747, he learned that three days earlier his father had died. In language typical of the dutiful oldest son whose closest tie was to the family patriarch, he lamented the death of “my best friend my dear Father…. As he was a tender & affectionate Parent I am under great concern for my Loss.” Named coexecutor of the will along with his stepmother, Henry spent the next three months settling his father’s estate. Both Henry and James received property, while their three married sisters were each granted fifty pounds in current money.7

Henry decided to settle in Charleston and in 1748 he formed a partnership with George Austin, a native of Shropshire, England. Austin & Laurens, joined in 1759 by Austin’s nephew George Appleby, became one of the leading merchant firms in Charleston and brought extensive wealth to the partners. They traded in rice, indigo, and deerskins, the primary commodities in South Carolina, and profited greatly from their involvement in the slave trade. The firm also invested in ships that operated in the West Indies. Laurens’s methodical work habits proved a major factor in the firm’s success. Requiring less sleep than most people, he often wrote letters by candlelight during the early hours of the morning. Indeed, he “frequently had the business of the day not only arranged, but done, when others were beginning to deliberate on the expediency of leaving their beds.” In his business dealings, he was punctual, diligent, and fair; he expected the same from other men. A deeply religious man, his strict moral code and great capacity for work made him intolerant of others less endowed with these qualities, both in business and in politics.8

The next move for the rising young merchant was marriage. According to tradition, Laurens met his future wife, Eleanor Ball, at her brother’s wedding, and fell in love with her immediately. On 25 June 1750 they married. The union proved both propitious and happy: as the Balls were an established and prestigious low-country family, Henry secured his position among the colony’s elite; and his business acumen and industriousness were matched by Eleanor’s abilities in the domestic sphere. The available evidence suggests that theirs was a “companionate marriage,” one that juxtaposed Henry’s patriarchal control with genuine love and friendship. Henry’s occasional mention of Eleanor in letters reveals a loving and attentive spouse and mother who enjoyed gardening and excelled in the duties expected of a wife, such as cooking and sewing. These references aside, she remains a veiled figure; a full picture of her never emerges.9

The couple had twelve children, of whom only four reached adulthood. Their first son, Henry, was born in 1753. On 28 October 1754 Eleanor gave birth to a second son, named John in honor of his grandfather. Known as Jack, the boy displayed early evidence of talent. At the age of three “he began of his own Accord to draw,” and proceeded to copy everything he saw. Jack found the world around him fascinating, both the dust and dash of mercantile Charleston and the flora and fauna of the Carolina coastal plain.10

In 1755 the first daughter to survive infancy, Eleanor, whom the family called Nelly, was born. Near in age, the three siblings formed a close-knit team of playmates. It was a happy childhood, supervised by loving and attentive parents, marred only by the specter of death. In August 1758 the younger Henry died. His death was Jack’s first encounter with the transitory nature of life, where a loved one’s existence seemingly vanished like a mist. Yet life continued and the family grew in size, though death would remain an ever-present reality. A year later Eleanor gave birth to another daughter, Martha, whom the family called Patsy.11

Following the steps of other prosperous merchants, Henry Laurens diversified his economic investments. In 1756 he purchased a half interest in Wambaw, a 1,250–acre rice plantation on the Santee River. His brother-in-law, John Coming Ball, managed the plantation, allowing Henry to devote his primary attention to business in Charleston. Ownership of land qualified him for a position in the Commons House of Assembly, and he took a seat in that body on 6 October 1757.12

Unlike socially stratified European countries such as Britain and France, the American colonies lacked a genuine nobility. In the colonies wealth was more widely dispersed and a large percentage of white men owned property, which was the criterion that defined autonomous individuals. The richest men in the provinces did not accumulate property to match that held by the English aristocracy; rather, their resources paralleled the prosperity of the English upper middle class. The colonies did, however, possess a natural aristocracy, the men of ability whose property provided them the leisure to live as gentlemen and function as political and social leaders. In South Carolina these gentlemen served in the Commons House of Assembly. Henry’s rise to prominence as a merchant, his marriage to Eleanor and ties to the Ball family, his ownership of land, and his election to the Commons House all confirmed him as a Carolina gentleman, a member of the province’s patrician class.13

Laurens quickly rose to prominence in the Commons House, where he served at intervals for the next fourteen years. Just as the colony’s gentlemen modeled their behavior and lifestyle after the English aristocracy, their assembly took for its model the House of Commons in the British Parliament. In what most British subjects considered a balanced government, the Commons protected the rights of Englishmen of property against encroachments by the crown and the House of Lords, which represented the nobility. The Commons House of Assembly viewed itself in a similar light. Throughout the eighteenth century, the assembly gradually increased its power at the expense of the royal governor and the upper house, the council. A seat in the assembly brought both prestige and training in the art of governing. The recurring struggle for power with various governors and the council provided lower house members with valuable political experience.14

Despite some personal differences, the political leaders who sat in the assembly maintained a surprisingly united front on most issues of public import. The colony’s prosperity made harmony both possible and necessary. Shared wealth precluded the clash of economic interests among the low-country elite. Yet they owed that wealth to the labor of an overwhelming slave majority. In Charleston, the center of political authority, the ratio of blacks to whites was about even, but in the surrounding low-country parishes dotted by rice plantations, slaves outnumbered whites as much as 7 to 1. The fear of slave insurrections required that whites remain unified and vigilant. At the same time, slaves served as a constant reminder to whites of the consequences of losing one’s freedom. Above all else, whites valued their personal independence, which was based on economic independence, their ownership of land and slaves.15

As Henry Laurens gained experience in politics, he continued to expand his landholdings. On 5 June 1762 he purchased Mepkin plantation on the Cooper River, about thirty miles from Charleston. Three months later, on 7 September, he bought land in Ansonborough, a neighborhood just outside Charleston. At both places, Henry constructed houses and laid out gardens that he intended to use as his town and country residences. At Ansonborough, he built a wharf that enabled schooners to travel from there to his country plantations. Next to him lived Christopher Gadsden, formerly his close friend but now a political adversary. Gadsden laid out streets in Ansonborough, connecting the neighborhood with Charleston proper.16

Young John Laurens spent his formative years at Ansonborough and Mepkin. His father spared no expense in creating an idyllic setting at both locations. Located on a high bluff overlooking Cooper River, Mepkin provided an escape from Charleston, particularly during the warm months, when tropical diseases threatened. Mepkin’s tranquil beauty was accentuated by a long avenue of tall live oaks that led to the plantation house. Henry and Eleanor worked together to construct a beautiful house and garden at their town residence. After giving birth on 25 August 1763 to a son, Henry, who was always called Harry by the family, Eleanor devoted personal attention to the four-acre garden, which contained exotic plants and fruit trees. In March 1764 the Laurenses finally occupied their new home. Henry described his dwelling as “a large elegant brick House of 60 feet by 38.” The garden was “pleasantly situated upon the River,” he wrote. “All this land about Ansonburgh is covered with fine Houses.”17

As members of the provincial elite, the Laurenses wanted their home to reflect a genteel lifestyle. Their house and garden served as a performance piece, a public exhibit of their refinement. On entering the mansion, a guest beheld several examples of gentility: fine china for display and for formal dinners; a harpsichord on which the girls practiced and performed; a bookcase with volumes that illustrated Henry’s breadth of knowledge. Most distinctive of all was the garden. Surrounded by a brick wall, the garden measured 200 yards in length, 150 yards in width. Henry and Eleanor planted an assortment of exotic flora, including a grape vine and banana, fig, olive, and orange trees. The diversity of plants and trees served a dual function: as supplements to the family diet and as conversation pieces when the Laurenses took guests on garden tours.18

For John Laurens, the home at Ansonborough served as a quiet haven that contrasted with the commotion of his bustling hometown. The Charleston of John’s youth contained over eleven thousand inhabitants. Situated on a peninsula bounded by the Ashley and Cooper Rivers, the city had been planned well. Its wide, unpaved streets, which intersected at right angles, allowed breezes to circulate, thus making life more bearable during the sultry summer months. As the provincial capital and principal port, the city served as the hub of political and economic life. The wealthiest, most influential members of Carolina society resided there for at least part of each year. Their lifestyle befitted their affluence. “No other American city can compare with Charleston in the beauty of its houses and the splendor and taste displayed therein,” commented one visitor.19

With wealth gleaned from the labor of slaves, the low-country elite lived in comfortable leisure. It seemed, at least to puritanical observers, that the affluent residents of Charleston had sunk to new depths of slothfulness. They spent much time playing cards, gambling, and attending horse races. Doctor Alexander Garden, a prominent physician and naturalist who became a mentor to John Laurens, described these self-styled aristocrats as “absolutely above every occupation but eating, drinking, lolling, smoking, and sleeping, which five modes of action constitute the essence of their life and existence.” While growing up, John thus encountered the tension between the luxur...